The 'Renvoi' Doctrine in Action: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on International Inheritance and Conflict of Laws

Date of Judgment: March 8, 1994

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

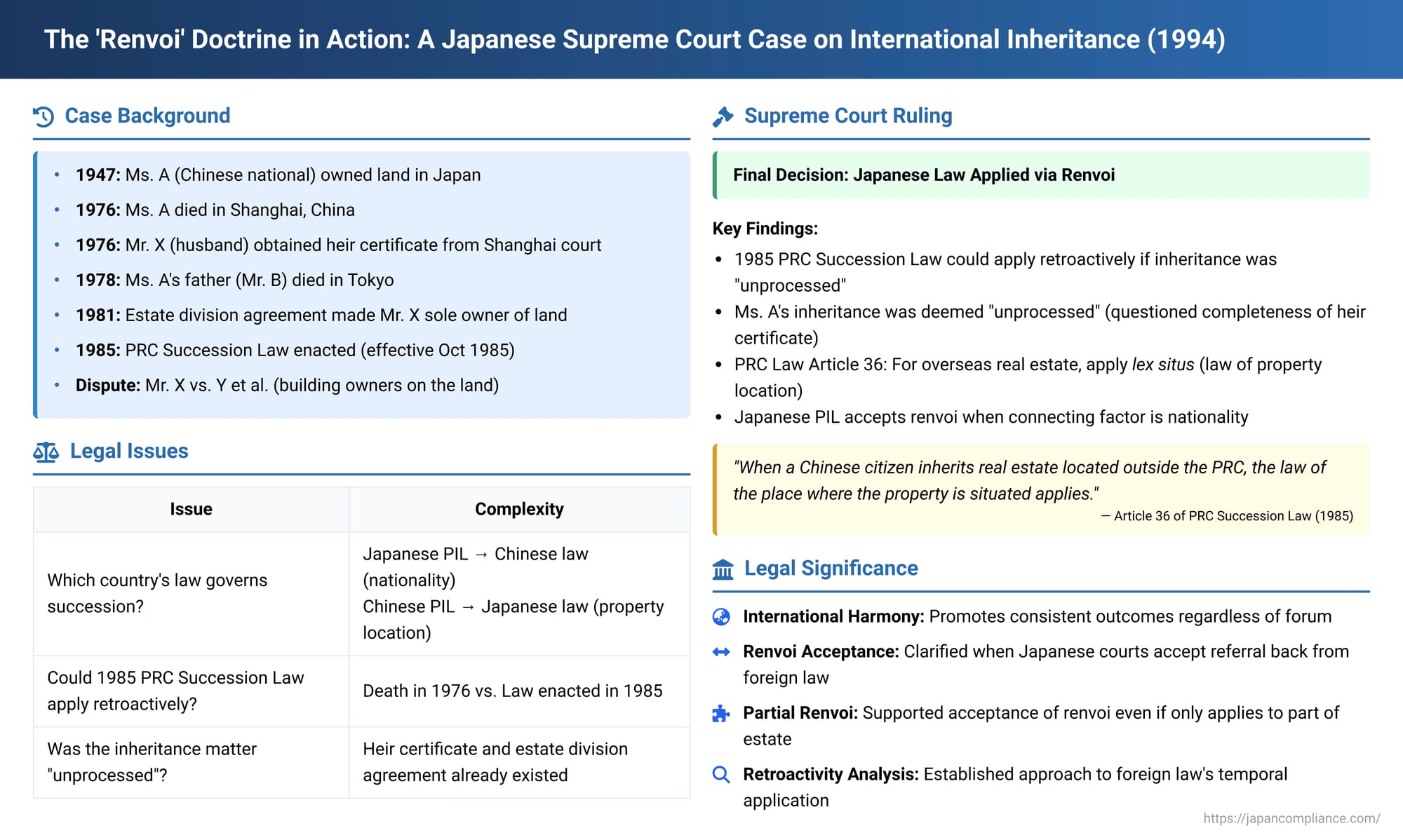

In the realm of private international law (also known as conflict of laws), legal practitioners and courts often encounter situations where the laws of different countries point in different directions. One fascinating doctrine that attempts to resolve such complexities is "renvoi" (反致 - hanchi). Renvoi occurs when the conflict of laws rules of the forum (the country where the case is heard) direct the court to apply the law of a foreign country, but the conflict of laws rules of that foreign country, in turn, direct back to the law of the forum or to the law of a third country. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from March 8, 1994, provides a compelling illustration of how this doctrine is applied in the context of an international inheritance dispute involving Japanese real estate.

The Factual Tapestry: An Estate Spanning Nations

The case involved a complex set of facts and relationships:

- Mr. X, a Chinese national, was the plaintiff. He had married Ms. A, also a Chinese national, in 1949.

- Ms. A had acquired a parcel of land in Japan ("the Land") by purchase around 1947. She passed away in Shanghai, China, in November 1976.

- A building situated on the Land ("the Building") had been acquired around 1947 by Ms. A's father, Mr. B, who was of Taiwanese origin. Mr. B passed away in Tokyo in May 1978.

- Following Ms. A's death, in December 1976, Mr. X and the four children he had with Ms. A obtained an official certificate from the Shanghai High People's Court in China, attesting to their status as Ms. A's heirs.

- On December 8, 1981, Mr. X and these four children, acting as Ms. A's heirs, entered into an estate division agreement. This agreement stipulated that Mr. X would become the sole owner of the Land.

- The Building on the Land was subsequently inherited and became co-owned by a group of individuals, Y et al. These individuals were the children of Mr. B (Ms. A's father) from his de facto marital relationships (内縁関係 - naien kankei) with several women.

- The lawsuit arose when Mr. X, asserting his sole ownership of the Land based on the estate division agreement, sued Y et al. (the co-owners of the Building) seeking, among other things, their eviction from the Land.

The Initial Legal Conundrum: Which Country's Law Governs?

The first question for the Japanese courts was to determine which country's laws should govern the succession to Ms. A's estate, particularly the Land located in Japan. According to Japan's prevailing private international law rules at the time (Article 25 of the old Horei, the Act on Application of Laws, principles of which are now in Article 36 of the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws), matters of succession were generally governed by the national law of the deceased. Since Ms. A was a Chinese national, this rule pointed to Chinese law.

The trial court (Tokyo District Court) applied Chinese law, finding that China had unwritten rules concerning the inheritance of overseas assets by its nationals that would allow Chinese law to govern the Japanese real estate.

The High Court's Introduction of Renvoi

The Tokyo High Court, on appeal, agreed that Chinese law was the initially designated law. However, it introduced a significant development by considering China's own conflict of laws rules. Specifically, it looked at Article 36 of the People's Republic of China (PRC) Succession Law, which was adopted on April 10, 1985, and became effective on October 1, 1985 – notably, after Ms. A's death but during the course of the litigation.

Article 36 of the PRC Succession Law stipulated that when a Chinese citizen inherits real estate located outside the PRC, the law of the place where the property is situated (the lex situs or 不動産所在地法 - fudōsan shozaichi hō) applies.

This created the classic scenario for renvoi:

- Japanese PIL pointed to Chinese law (as Ms. A's national law - 本国法, honkoku hō).

- Chinese PIL (specifically, PRC Succession Law Art. 36) pointed back to Japanese law (as the law of the Land's location).

The High Court held that this PRC law applied retroactively to Ms. A's succession and, consequently, a renvoi from Chinese law to Japanese law was established for both the inheritance of the Land and the validity of the estate division agreement. Y et al. appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that while Chinese law should apply, the estate division agreement was invalid under that law, and challenged the High Court's choice-of-law reasoning.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation and Elaboration of Renvoi

The Supreme Court of Japan, in its March 8, 1994 judgment, ultimately upheld the High Court's conclusion that Japanese law applied, thereby dismissing the appeal of Y et al. (except for one appellant whose appeal was dismissed on procedural grounds). The Supreme Court's reasoning provides a detailed look into the application of renvoi.

1. Retroactive Application of the PRC Succession Law

The Supreme Court first confirmed that the law applicable to Ms. A's succession was, according to Japanese PIL, her national law – PRC law. It then addressed whether the 1985 PRC Succession Law, with its critical Article 36, could be applied retroactively to Ms. A's death in 1976. The Court noted:

- Explanations provided by the PRC People's Congress indicated that if an inheritance commenced before the 1985 Law's effective date, it would not be reprocessed if already dealt with; however, if it was "unprocessed" at the time the new law came into force, the new law would apply.

- An opinion from the PRC Supreme People's Court stated that for inheritance cases accepted by courts before the 1985 Law took effect but not yet concluded, the new law should be applied.

- This retroactive application was based on the understanding that the fundamental principles of the 1985 Law were consistent with customary law and legal principles existing in the PRC even before its formal enactment.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that if Ms. A's succession was indeed "unprocessed" when the PRC Succession Law became effective in October 1985, its provisions would apply retroactively.

2. Determining if the Inheritance was "Unprocessed"

The next crucial step was to determine if Ms. A's succession was, in fact, "unprocessed" in 1985. The Supreme Court examined the evidence:

- Mr. X and his children had obtained an Heirship Certificate in December 1976 from the Shanghai High People's Court, which stated that Ms. A's property in Japan (the Land) should be inherited by Mr. X (her husband) and their four children.

- However, Article 10 of the PRC Succession Law listed the spouse, children, and parents of the deceased as first-order statutory heirs. The Court also noted that available information suggested that PRC customary law prior to the 1985 Law recognized the same order of heirs.

- Ms. A's father, Mr. B, was alive at the time the Heirship Certificate was issued in 1976.

- The Certificate made no mention of Mr. B. The Supreme Court expressed doubt that this Certificate definitively proved Mr. B was not an heir.

- Mr. X relied on the 1981 estate division agreement (遺産分割協議 - isan bunkatsu kyōgi), made among himself and the four children, which designated him as the sole inheritor of the Land.

- Given the questions surrounding the completeness of the Heirship Certificate (specifically, the omission of a potential first-order heir, Mr. B), the Court found the validity of the estate division agreement based upon it to be immediately questionable.

Based on these uncertainties and potential flaws in the prior handling of the heirship, the Supreme Court concluded that this situation did not prevent a finding that Ms. A's succession issue was "unprocessed" when the PRC Succession Law took effect.

3. Affirming Renvoi to Japanese Law

With the 1985 PRC Succession Law deemed retroactively applicable, and the matter considered "unprocessed," Article 36 of that law came into play. This article directed that the inheritance of Ms. A's overseas real estate (the Land) be governed by the law of its situs, which was Japan.

Japan's own private international law (Article 29 of the old Horei, now Article 41 of the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws) permitted renvoi when the primary connecting factor for choice of law was nationality. Therefore, the reference by Chinese law back to Japanese law was accepted.

The Supreme Court concluded that, as a result of this renvoi, Japanese law was the ultimate governing law for the succession to the Land. The High Court's judgment, which had reached the same conclusion, was thus affirmed in its outcome.

The Doctrine of Renvoi Explained

"Renvoi" is a French term meaning "sending back" or "transmission." In private international law, it refers to a situation where:

- The conflict of laws rules of the forum (e.g., Japan) select the law of a foreign country (e.g., China) to govern a case.

- The conflict of laws rules of that foreign country (China) then refer the matter either:

- Back to the law of the forum (Japan) – this is called "remission" or simple renvoi.

- To the law of a third country – this is called "transmission."

The traditional purpose of recognizing renvoi is to promote "international harmony of decisions" by trying to ensure that the same substantive law is applied to a case regardless of where it is heard, or at least to apply the law that the designated foreign system itself would apply to the international aspects of the case.

Japanese law, under both the old Horei and the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws (Article 41), generally accepts simple renvoi (remission) when its rules direct the application of a person's national law, subject to certain exceptions.

Scholarly Discussion on the Court's Reasoning

While the Supreme Court's final outcome on renvoi was largely in line with prevailing views, its specific reasoning for deeming the inheritance "unprocessed" attracted some academic attention. The commentary provided notes that some scholars have criticized the Court for delving into substantive aspects of Chinese heirship law (e.g., who are the rightful heirs, the validity of the prior certificate and agreement) as a prerequisite to deciding whether the Chinese choice-of-law rule (Art. 36 of the 1985 Law) applied. The argument is that such substantive evaluations should ideally occur only after the governing law has been definitively established through the choice-of-law process, including any renvoi. The determination of whether an estate was "unprocessed" for the purpose of retroactive application of a choice-of-law statute, these critics suggest, should be based on more objective, procedural, or factual criteria (e.g., whether court proceedings were pending or whether the estate had been factually distributed) rather than a pre-judgment of the merits under a potential governing law.

Interestingly, the commentary points out that the PRC Supreme People's Court's own judicial interpretation regarding the retroactive application of the 1985 Succession Law seemed to focus on whether court cases were already accepted and pending. If such criteria were strictly applied to this case (where various related lawsuits were filed in 1983, 1985, and 1986), the 1985 PRC Succession Law would likely have been applicable anyway, leading to the same outcome of renvoi to Japanese law. Thus, the conclusion is deemed appropriate, even if the specific path taken to the "unprocessed" finding is debated.

Broader Concepts Related to Renvoi

The case and the accompanying commentary also touch upon wider aspects of the renvoi doctrine:

- Double Renvoi (二重反致 - nijū hanchi): This considers whether the forum court should also examine the foreign law's own rules on accepting or rejecting renvoi. For example, if Japanese PIL points to Chinese law, and Chinese PIL points back to Japanese law, should the Japanese court investigate if Chinese PIL would itself accept a renvoi from another country pointing to Chinese law, or if it would reject the "return" from Japan? This can lead to complex, sometimes circular, reasoning. At the time of this judgment, PRC private international law did not have clear statutory provisions on renvoi, making this less of a direct issue in this specific case.

- Partial Renvoi (部分反致 - bubun hanchi): This issue arises if the foreign law designated by the forum's PIL adopts a "scission" system for succession (applying different laws to movables and immovables), while the forum itself might prefer a unitary system (one law for the entire estate). Could renvoi then apply to only one part of the estate (e.g., the foreign law refers immovables to their situs law, but movables to the deceased's domiciliary law)? While there was once influential opinion against partial renvoi in Japan to maintain its then-unitary approach to succession, the prevailing view, supported by the commentator, is that partial renvoi should be accepted to foster international decisional harmony, despite potential administrative complexities.

Conclusion: A Practical Application of a Complex Doctrine

The Supreme Court's March 8, 1994 decision is a significant illustration of the renvoi doctrine in practical application within Japanese private international law. It demonstrates how a matter initially appearing to be governed by foreign law can, through the interplay of different countries' conflict of laws rules, ultimately be decided under Japanese domestic law. The Court navigated the retroactive application of a foreign statute and the factual assessment of prior estate handling to arrive at a conclusion that embraced renvoi, aiming for a resolution that aligned with the principles of both Japanese and Chinese conflict of laws pertaining to real estate. This case underscores the judiciary's role in untangling complex international legal knots, often striving for outcomes that are both legally sound and internationally coherent.