The "Question Before the Question": Japan's Supreme Court Clarifies Choice of Law for Preliminary Issues in International Cases

Date of Judgment: January 27, 2000

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

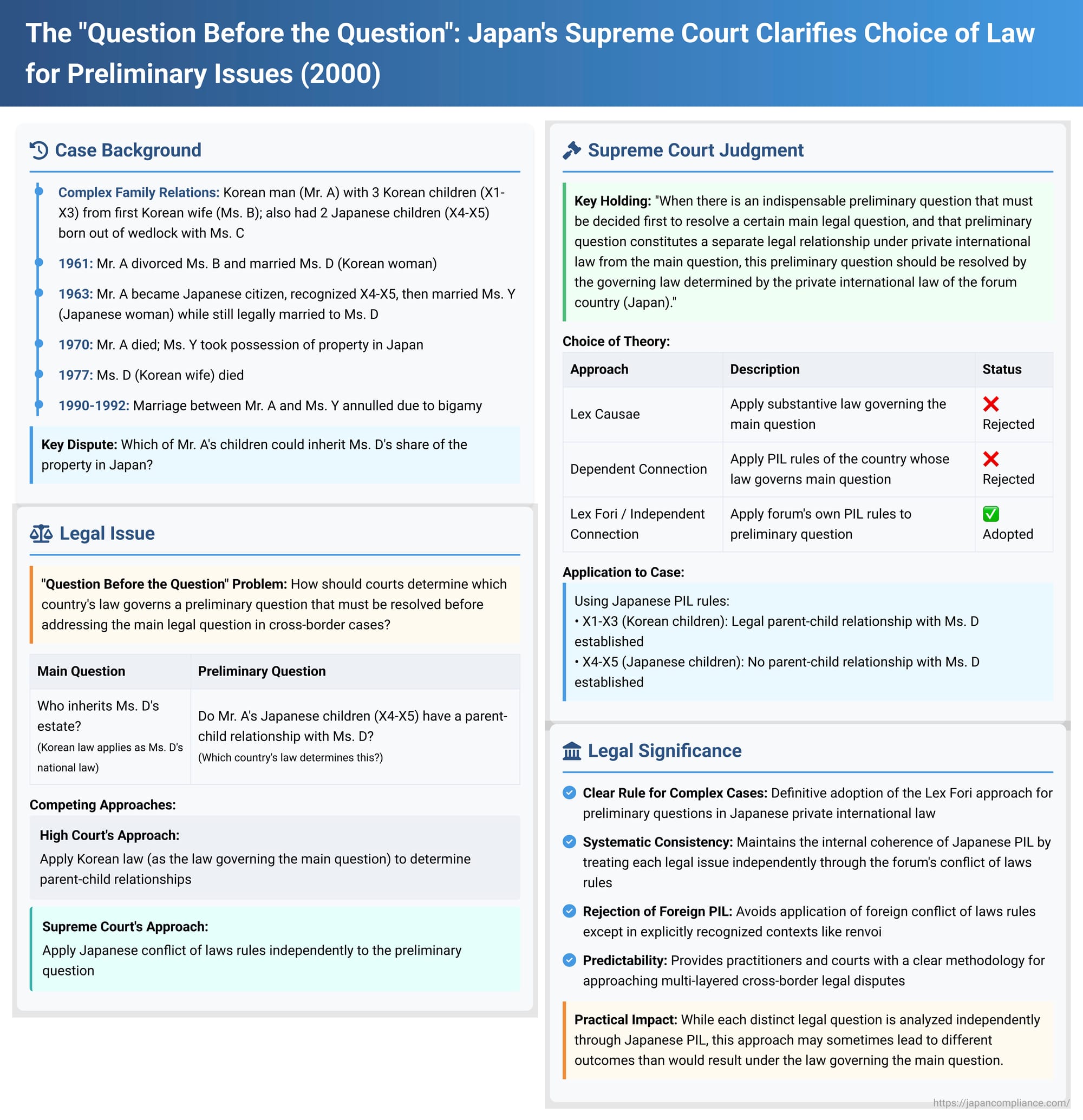

International legal disputes, particularly those involving family matters and inheritance across borders, often resemble a complex web of interconnected issues. To resolve the main legal question presented to a court, it sometimes becomes necessary to first answer one or more underlying, or "preliminary," questions. A critical issue in private international law (also known as conflict of laws) is determining which country's laws should govern these preliminary questions. On January 27, 2000, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment that provided significant clarity on this very point, establishing a clear approach for Japanese courts.

An Intricate Family Saga Across Borders

The factual background of the case was remarkably complex, involving multiple nationalities, marriages, and family relationships spanning several decades:

- Mr. A: Originally a Korean national (named Kang Chang-Soo).

- He first married Ms. B, a Korean woman, with whom he had three children: X1, X2, and X3 (all Korean nationals).

- Mr. A also had an extramarital relationship with Ms. C, a Japanese woman, resulting in two children born out of wedlock: X4 and X5 (both Japanese nationals).

- Mr. A's Subsequent Marital History and Naturalization:

- In 1961, Mr. A divorced Ms. B.

- Later in 1961, he married Ms. D (Ko Rok-Son), a Korean woman residing in Korea.

- In 1963, Mr. A naturalized as a Japanese citizen, adopting the name Okayama Shoki. Importantly, his new Japanese family register did not include any record of his marriage to Ms. D.

- Also in 1963, Mr. A legally recognized his children X4 and X5.

- Then, still legally married to Ms. D (a fact not recorded in his Japanese family register), Mr. A entered into a marriage with Ms. Y, a Japanese woman, in Japan. This marriage to Ms. Y was, therefore, bigamous. Mr. A lived with Ms. Y, and his recognized children X4 and X5.

- Deaths and Disputes:

- Mr. A passed away in 1970. His estate included land and a building in Japan (the "Property").

- After Mr. A's death, Ms. Y took sole possession and management of the Property, collecting rents. Around 1971, Ms. Y became aware of Mr. A's prior and existing marriage to Ms. D.

- Ms. D (Mr. A's Korean wife) passed away in 1977.

- In 1990, X4 (one of Mr. A's children with Ms. C) initiated legal action to annul the marriage between Mr. A and Ms. Y on the grounds of bigamy, given Mr. A's pre-existing marriage to Ms. D. This annulment was granted and became final on March 3, 1992.

- The Consolidated Lawsuits before the Courts:

- Case 1: X4 sued Ms. Y, seeking eviction from the Property's building and payment of a sum equivalent to rents received by Ms. Y, based on X4's asserted share in the Property.

- Case 2: Ms. Y sued all of Mr. A's children (X1, X2, X3, X4, and X5), claiming she had acquired full title to the Property through acquisitive prescription (similar to adverse possession).

The Core Legal Puzzle: Inheritance and the Parent-Child Link

A central issue in determining the parties' respective rights to the Property was the inheritance of Ms. D's share. Ms. D, as Mr. A's lawful spouse (under Korean law and recognized as such for succession purposes to A's estate), had inherited a portion of Mr. A's estate upon his death. When Ms. D herself died, the question arose: who would inherit her share, which included her interest in the Japanese Property?

Under Japanese private international law (the old Horei, Article 25, similar to the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws, Article 36), the succession to Ms. D's estate (the "main question") was to be governed by her national law at the time of her death, which was Korean law. Korean law, like many succession laws, designates "children" or "direct descendants" as primary heirs.

This led to the "preliminary question": Could X4 (Mr. A's Japanese child with Ms. C, recognized by Mr. A) be considered a "child" or "direct descendant" of Ms. D (Mr. A's Korean wife) for the purpose of inheriting from Ms. D under Korean law? The answer to this preliminary question of parentage was crucial for determining X4's total share in the Property.

The High Court's Approach to the Preliminary Question

The Osaka High Court, the lower appellate court, addressed the preliminary question of the parent-child relationship between Ms. D and X4. It determined that this question should be resolved by applying Korean law, the same law that governed the main question of Ms. D's inheritance. The High Court found that under the old Korean Civil Code (specifically Article 774 and related provisions), a legal relationship known as a "stepmother-stepchild relationship" (嫡母庶子関係 - chakumo shoshi kankei) could be established between a husband's wife (Ms. D) and the husband's recognized illegitimate children (like X4). This relationship had implications for inheritance. Consequently, the High Court recognized X4 as an heir to Ms. D, thereby increasing X4's share in the disputed Property. Ms. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: The "Lex Fori" Governs Preliminary Questions

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of January 27, 2000, partially overturned the High Court's decision. Critically, it laid down a clear and definitive rule for handling preliminary questions in Japanese private international law:

"In a transnational legal relationship, when there is an indispensable preliminary question that must be decided first to resolve a certain main legal question, and that preliminary question constitutes a separate legal relationship under private international law from the main question, this preliminary question should be resolved not by the governing law of the main question, nor by the governing law designated by the private international law of the country to which the governing law of the main question belongs, but by the governing law determined by the private international law of the forum country, which is Japan."

In simpler terms, the Supreme Court mandated that Japanese courts must use Japanese private international law rules to determine the governing law for a preliminary question, independently of the law governing the main question.

Applying this principle to the case:

- Main Question: Succession to Ms. D's estate. Governed by Korean law (as determined by Japanese PIL).

- Preliminary Question: Does a parent-child relationship exist between Ms. D and X4 (and other children of A)? This is a distinct legal issue from succession itself.

- Supreme Court's Direction: The governing law for determining this parent-child relationship must be found by applying Japan's own private international law rules for establishing parentage.

This was a significant departure from the High Court's approach.

Understanding the Theories on Preliminary Questions

The Supreme Court's choice aligns with one of several established theories on how to determine the law applicable to preliminary questions:

- Lex Causae Approach (Substantive Law of the Main Question): This approach suggests that the preliminary question should be resolved by the substantive rules of the law governing the main question. For instance, if Korean law governs Ms. D's succession and refers to "children," then Korean substantive law would define who qualifies as a "child." This was, in effect, the High Court's method.

- Dependent Connection / Renvoi-like Approach (PIL of the Main Question's Law): This theory proposes using the private international law rules of the country whose substantive law governs the main question. So, one would look to Korean PIL rules to find the law governing parentage.

- Lex Fori Approach / Independent Connection (PIL of the Forum): This approach, adopted by the Japanese Supreme Court, dictates that the forum court (the Japanese court, in this instance) should apply its own private international law rules to the preliminary question as if it were an independent issue. The preliminary question is characterized separately, and a connecting factor is applied according to the forum's PIL system to determine the applicable substantive law.

- Eclectic Approach: This seeks a flexible solution, generally following the Lex Fori approach but allowing for the Dependent Connection approach in certain circumstances, such as when the preliminary issue has little connection to the forum, and harmonizing with the outcome under the main law's jurisdiction seems more appropriate.

The Supreme Court's judgment unequivocally endorsed the Lex Fori (Independent Connection) approach. By not adding any qualifications like "in principle," the Court is understood to have also rejected the more flexible Eclectic Approach.

Rationale for the Lex Fori Approach

The commentary accompanying the case suggests several reasons for favoring the Lex Fori approach:

- Structural Consistency of Private International Law: PIL systems are generally structured to classify different legal issues into distinct "legal relationships" (e.g., marriage, contract, tort, succession, parentage) and then apply specific choice-of-law rules (connecting factors) to each. Treating a preliminary question as just another independent legal relationship to be processed through the forum's PIL rules maintains this structural consistency.

- Avoidance of Foreign PIL (Except for Renvoi): Courts typically apply their own country's PIL rules. Resorting to the PIL rules of another country (as in the Dependent Connection approach) is generally avoided, with renvoi (where the forum's PIL directs to a foreign law, and that foreign law's PIL refers back to the forum or to a third country's law) being a recognized, but often limited, exception. The commentary notes that renvoi was the sole codified exception allowing consideration of foreign PIL.

- Denial of the "Preliminary Question" as a Special Problem: Adopting the Lex Fori approach effectively means that "preliminary questions" are not treated as a unique or problematic category requiring special rules. Instead, any issue, whether main or preliminary, is subjected to the forum's standard PIL process. This places the burden of argument on those who would advocate for a departure from this standard methodology.

Applying Japanese PIL to the Parent-Child Link

Having decided that Japanese PIL rules would determine the law governing the parent-child relationship between Ms. D and Mr. A's various children, the Supreme Court then proceeded with that analysis. This involved applying specific articles of Japan's old Horei concerning the establishment of parent-child relationships (legitimacy, effects of marriage on stepchildren, recognition, etc.). The outcome was as follows:

- For X1, X2, and X3 (Mr. A's Korean children with his first wife, B): When Mr. A (then Korean) married Ms. D (Korean), Japanese PIL would look to Mr. A's national law at the time of his marriage to Ms. D (i.e., Korean law) to determine if this marriage made X1, X2, and X3 the legitimate (step)children of Ms. D. The Supreme Court found that under the relevant (since amended) Korean Civil Code, a legal stepmother-child relationship (継母子関係 - keiboshi kankei) with inheritance rights was indeed established between Ms. D and X1, X2, and X3. Thus, they were heirs to Ms. D.

- For X4 and X5 (Mr. A's Japanese children with Ms. C, whom Mr. A later recognized): Mr. A recognized X4 and X5 after he had become a Japanese national. Japanese PIL would primarily look to Japanese law (as Mr. A's national law at the time of recognition) to determine the effect of this recognition on Ms. D (Mr. A's then-wife). Japanese law did not automatically create a parent-child relationship between Ms. D and her husband's recognized illegitimate children from another union.

Furthermore, for establishing any other form of non-biological, non-legitimating parent-child link between Ms. D and X4/X5, the Supreme Court, interpreting the principles of the old Horei, held that such a relationship could only be affirmed if the laws of both the potential parent (Ms. D's Korean law) and the child (X4/X5's Japanese law) at the time of the relevant connecting fact (e.g., Mr. A's recognition of X4/X5) supported its creation. Since Japanese law did not establish such a link between Ms. D and X4/X5, they were found not to be Ms. D's legal heirs, regardless of what Korean law might have provided on its own.

Consequences and Other Aspects of the Ruling

This determination regarding heirship directly impacted the calculation of X4's rightful share in the Property and, consequently, the amount of rent equivalent she could claim from Ms. Y. X4's inheritable share was limited to what she received directly from her father, Mr. A, and did not include any portion from Ms. D's estate.

The Supreme Court also addressed Ms. Y's claim of acquisitive prescription. It found that Ms. Y had successfully acquired by prescription the 1/3rd share of the Property that she would have legally inherited from Mr. A if her marriage to him had been valid. The Court reasoned that Ms. Y began her possession as Mr. A's presumed wife and heir, thus possessing with the "intent to own" as presumed by Article 186(1) of the Civil Code. Her later discovery of the bigamous nature of her marriage (a change in her subjective understanding) was not, by itself, sufficient to overturn this legal presumption of possessory intent, absent any external, objective change in the manner of her possession. She had possessed this share for the requisite 20-year period.

Conclusion: A Clear Rule for a Complex Problem

The Supreme Court's decision of January 27, 2000, stands as a significant pronouncement in Japanese private international law. By definitively adopting the Lex Fori (Independent Connection) approach for preliminary questions, the Court opted for a method that prioritizes the internal consistency and systematic application of the forum's own conflict of laws rules. This ruling provides a clear guiding principle for Japanese courts when faced with the "question before the question" in complex international disputes, ensuring that each distinct legal issue is channeled through the appropriate Japanese choice-of-law rules to find its governing substantive law. While the intricate facts of the case highlight the human complexities that can arise from cross-border lives and relationships, the legal principles articulated by the Court offer a structured pathway to their resolution within the Japanese legal system.