The Principle of Legality in Tax Exemptions: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: July 6, 2010

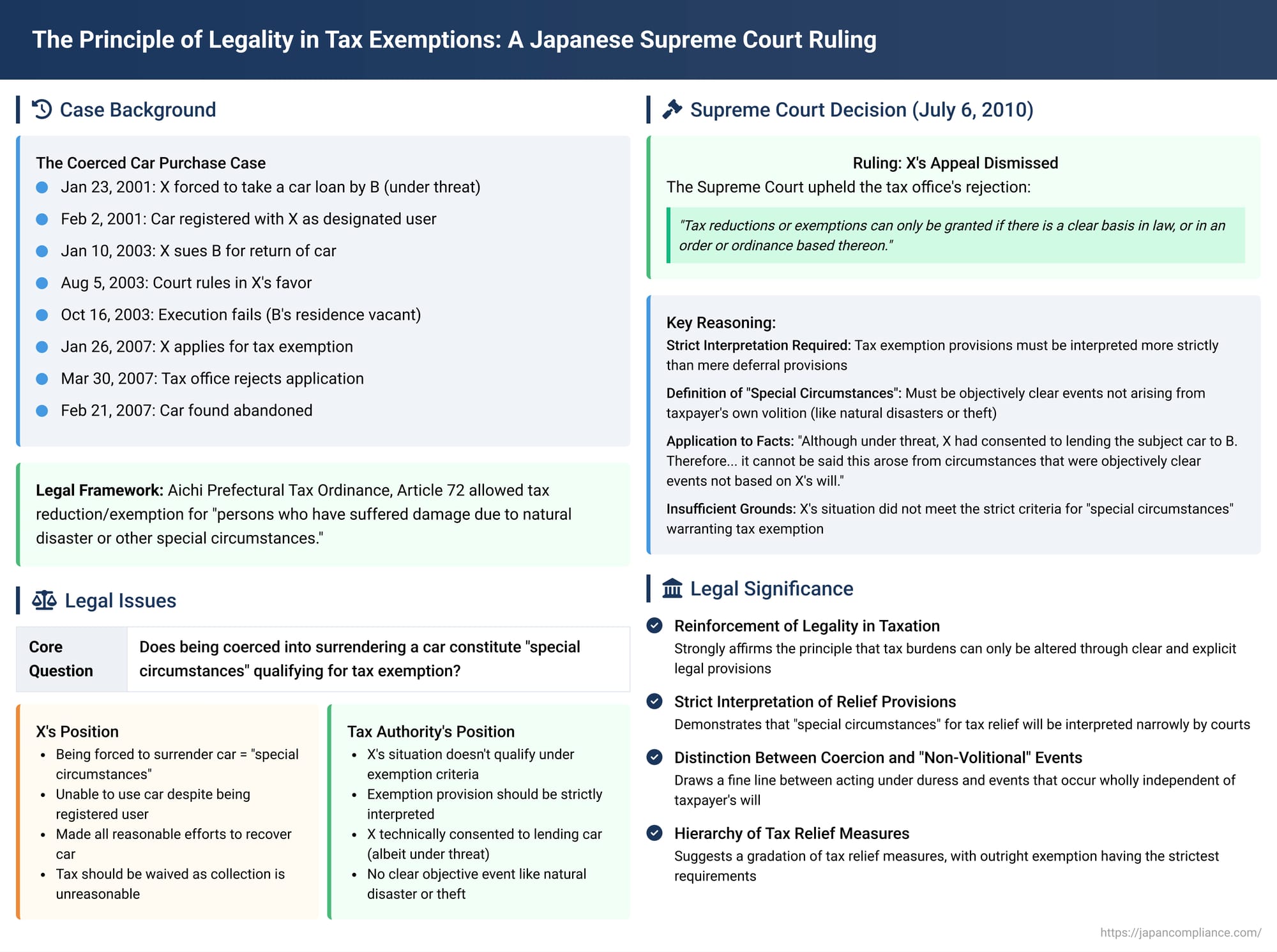

In a decision underscoring the paramount importance of the principle of legality in tax administration, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the conditions under which a taxpayer could be granted an exemption or reduction in automobile tax due to "special circumstances." The case involved a taxpayer who lost possession of his vehicle due to coercion and subsequently sought tax relief. The Court's ruling emphasized that tax exemptions require a clear legal basis and must be interpreted strictly, narrowly defining what constitutes "special circumstances" qualifying for such relief.

Factual Background: A Car Lost Through Coercion

The plaintiff, X (respondent on appeal), found himself in a difficult situation. On January 23, 2001, X was threatened by an individual named B, who held a title affiliated with an entity known as "A Information Propaganda Bureau." Under duress, X was compelled to take out an automobile loan with a finance company to purchase a car ("the subject car"). Immediately upon purchase, X handed the car over to B.

On February 2, 2001, the subject car was officially registered. The registration listed the finance company as the owner and X as the designated user, with X's address recorded as the user's address and the car's base of operation.

X did not passively accept this situation. On January 10, 2003, X filed a lawsuit against B in the Okazaki Branch of the Nagoya District Court, seeking the return of the subject car and repayment of loaned money. On August 5, 2003, the court ruled in X's favor. However, subsequent attempts to enforce this judgment and recover the vehicle (a movable property execution) proved futile, concluding on October 16, 2003, as B's residence was found vacant.

Years later, on January 26, 2007, X applied to the director of the Aichi Prefectural Tax Office (Toyota Kamo branch) for a reduction or exemption of the automobile tax assessed on the subject car for fiscal years 2005 and 2006. X argued that since approximately April 2001, B had effectively embezzled the car, X had not been in possession of it, and its whereabouts were unknown. X based this application on Article 72 of the Aichi Prefectural Tax Ordinance ("the Ordinance"), which stated: "The governor may grant a reduction or exemption of automobile tax to persons who have suffered damage due to natural disaster or other special circumstances, and for whom it is deemed necessary."

On March 30, 2007, the director of the tax office rejected X's application ("the subject rejection"), reasoning that X's situation did not fall under the exemption criteria stipulated in Article 72 of the Ordinance.

As a subsequent development, the subject car was discovered abandoned on a street in Nagoya City on February 21, 2007. It was officially deregistered (processed for scrapping) on July 18, 2007.

After an unsuccessful administrative review appeal to the Governor of Aichi Prefecture, X filed a lawsuit against Aichi Prefecture (Y, the appellant) seeking the cancellation of the subject rejection.

The Legal Framework for Automobile Tax Exemptions

The power of prefectures to grant automobile tax exemptions is rooted in national law:

- Local Tax Act, Article 162 (former version, now Article 177-17): This provision stipulated that a prefectural governor could grant a reduction or exemption of automobile tax to persons for whom it is deemed necessary due to natural disaster or other special circumstances, in accordance with the provisions of the relevant prefectural ordinance.

- Aichi Prefectural Tax Ordinance, Article 72: Enacted under the authority of the Local Tax Act, this article provided: "The governor may grant a reduction or exemption of automobile tax to persons who have suffered damage due to natural disaster or other special circumstances, and for whom it is deemed necessary." The Ordinance itself and its related regulations did not further define "special circumstances" or when an exemption is "deemed necessary."

- Aichi Automobile Tax Basic Circular (an internal administrative guideline): This circular listed specific instances where reduction/exemption might be considered:

- When a vehicle becomes inoperable for a considerable period due to damage to its engine, etc., caused by a natural disaster.

- When it is recognized that the owner could not possess the vehicle for a considerable period due to theft.

- Other special circumstances deemed necessary after consultation with the General Affairs Department Tax Division.

Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Ordinance also stipulated that the governor generally delegates administrative affairs concerning the assessment and collection of prefectural taxes to the director of the prefectural tax office governing the taxpayer's tax district.

Lower Court Rulings: A Divergence of Views

The Nagoya District Court (first instance) dismissed X's claim. It interpreted the phrase "persons who have suffered damage due to natural disaster or other special circumstances" in Article 72 of the Ordinance to mean cases where the taxpayer became unable to use the vehicle due to objectively clear circumstances for which the taxpayer bore no responsibility, such as damage from a natural disaster. The court also held that the decision to grant or deny an exemption fell within the reasonable discretion of the governor (and by delegation, the tax office director), considering the legal nature of automobile tax. It found no abuse of this discretion in X's case.

The Nagoya High Court (appellate court) reversed the District Court's decision and cancelled the tax office's rejection. The High Court considered the fact that X had been extorted, had made all possible efforts to recover the car (including legal action), and that the car was eventually found abandoned much later. It reasoned that if tax exemptions were granted in cases of theft, it would be unequal and unreasonable to deny an exemption in X's circumstances, particularly for the tax periods after the enforcement proceedings had failed. The High Court concluded that the tax office's rejection constituted an abuse of discretion. Aichi Prefecture then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Principle of Legality

The Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court's reasoning and ultimately reinstated the District Court's decision, meaning X's request for cancellation of the rejection was denied. The Supreme Court's judgment hinged on a strict interpretation of the legal requirements for tax exemptions.

I. Tax Exemptions Require Clear Legal Basis

The Court began by affirming a fundamental tenet of tax law:

"Considering the need to curb arbitrary actions by tax authorities and to ensure fairness in tax burdens, tax reductions or exemptions can only be granted if there is a clear basis in law, or in an order or ordinance based thereon."

This opening statement firmly anchors the decision in the principle of legality, which dictates that administrative actions, especially those involving taxation, must be strictly grounded in and consistent with legal provisions.

II. Interpreting "Natural Disaster or Other Special Circumstances"

The Court then proceeded to interpret the crucial phrase "natural disaster or other special circumstances" in Article 72 of the Ordinance.

- Purpose of the Exemption System: The Court explained that automobile tax reductions/exemptions under Article 162 of the Local Tax Act (which Article 72 of the Ordinance implements) are intended as a system of individual relief. This relief is for taxpayers whose ability to pay tax (担税力 - tanzeiryoku, or tax-bearing capacity) has been diminished or lost due to events like natural disasters, to such an extent that imposing the tax burden would be unreasonable, even after considering other measures available under the Local Tax Act (such as deferral of tax collection). Article 72 of the Ordinance, by allowing exemptions for those who have suffered damage to their property due to "natural disaster or other special circumstances," reflects this same purpose.

- Analogy to Tax Deferral Provisions: To understand the scope of "special circumstances," the Court drew an analogy to Article 15, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Local Tax Act. This provision deals with the deferral of tax collection for taxpayers who have suffered damage to their property. It explicitly lists the qualifying grounds as:

- "Earthquake, flood, fire, or other disaster"

- "Theft"

The Court highlighted that both categories represent situations where the taxpayer's ability to pay is diminished or lost due to circumstances that are objectively clear and not based on the taxpayer's will.

- Stricter Interpretation for Exemptions: The Court reasoned that the requirements for a tax exemption (which extinguishes the tax liability entirely) under Article 72 of the Ordinance should be interpreted more strictly than the requirements for a mere deferral of collection (which only postpones payment).

Therefore, the term "natural disaster or other special circumstances" as a requirement for tax exemption under Article 72 of the Ordinance must, at a minimum, refer only to circumstances that reduce the taxpayer's ability to pay and are objectively clear events not arising from the taxpayer's own volition. This interpretation, the Court found, aligns with the literal meaning of the text and is appropriate.

The Court also noted that efforts made by a taxpayer to recover from the damage (such as X's lawsuit against B) might be considered when determining whether granting an exemption is "necessary" for someone who already meets the criteria of having suffered damage due to "natural disaster or other special circumstances." However, such efforts are not directly relevant to the initial determination of whether the damage itself was caused by circumstances qualifying as "special circumstances."

III. Application to X's Case

Applying this strict interpretation to the facts, the Supreme Court found:

"According to the aforementioned facts, although it was the result of being threatened, X had consented to lending the subject car to B. Therefore, even if X suffered damage by being unable to use the purchased subject car, it cannot be said that this arose from circumstances that were objectively clear events not based on X's will. Consequently, this situation cannot be deemed to fall under 'natural disaster or other special circumstances.'"

In essence, the Court determined that X's initial act of "consenting" to lend the car to B, even though this consent was obtained under duress, took the situation outside the narrowly defined scope of "special circumstances." Unlike a straightforward case of theft where the owner's will plays no part in the initial loss of possession, or a natural disaster where the cause is entirely external, X's involvement, however coerced, was a distinguishing factor.

The Court concluded that the Aichi Prefectural Tax Office director's judgment that X did not meet the exemption requirements of Article 72 of the Ordinance at the time of the rejection was appropriate. No other grounds suggesting illegality in the rejection were found.

Judgment and Significance

The Supreme Court therefore reversed the Nagoya High Court's decision and upheld the first instance judgment of the Nagoya District Court, which had dismissed X's claim. The costs of the appeal and the second instance appeal were to be borne by X.

This judgment has significant implications:

- Reinforcement of Legality in Taxation: It strongly reinforces the principle that tax burdens can only be altered (including through exemptions or reductions) based on clear and explicit legal provisions. This limits administrative discretion and aims to ensure fairness and predictability in taxation.

- Strict Interpretation of Exemption Clauses: The case demonstrates that provisions granting tax relief, such as those for "special circumstances," are likely to be interpreted strictly and narrowly by the courts. The burden is on the taxpayer to demonstrate that their situation unequivocally falls within the defined legal criteria.

- Distinction Between Coercion and "Non-Volitional" Events: The Court drew a fine line between acting under duress and events that are "objectively clear as not being based on the taxpayer's will." The initial (albeit coerced) consent to lend the car was pivotal in the Court's view, distinguishing it from events like outright theft or natural disasters where no element of consent is present.

- Hierarchy of Relief Measures: The analogy to tax deferral provisions, and the reasoning that exemption requirements should be even stricter, suggests a judicial view of a hierarchy of tax relief measures, with outright exemption being the most exceptional.

While the outcome may seem harsh given X's victimization, the Supreme Court's decision prioritizes the objective application of tax law and the principle that deviations from standard tax obligations must be meticulously justified under existing legal frameworks. It sends a clear message about the limited scope for discretionary relief in the absence of unambiguous statutory or ordinance-based entitlement.