The Price of Waiting: Japan's Supreme Court on Mental Suffering from Delays in Minamata Disease Certification

Date of Judgment: April 26, 1991

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

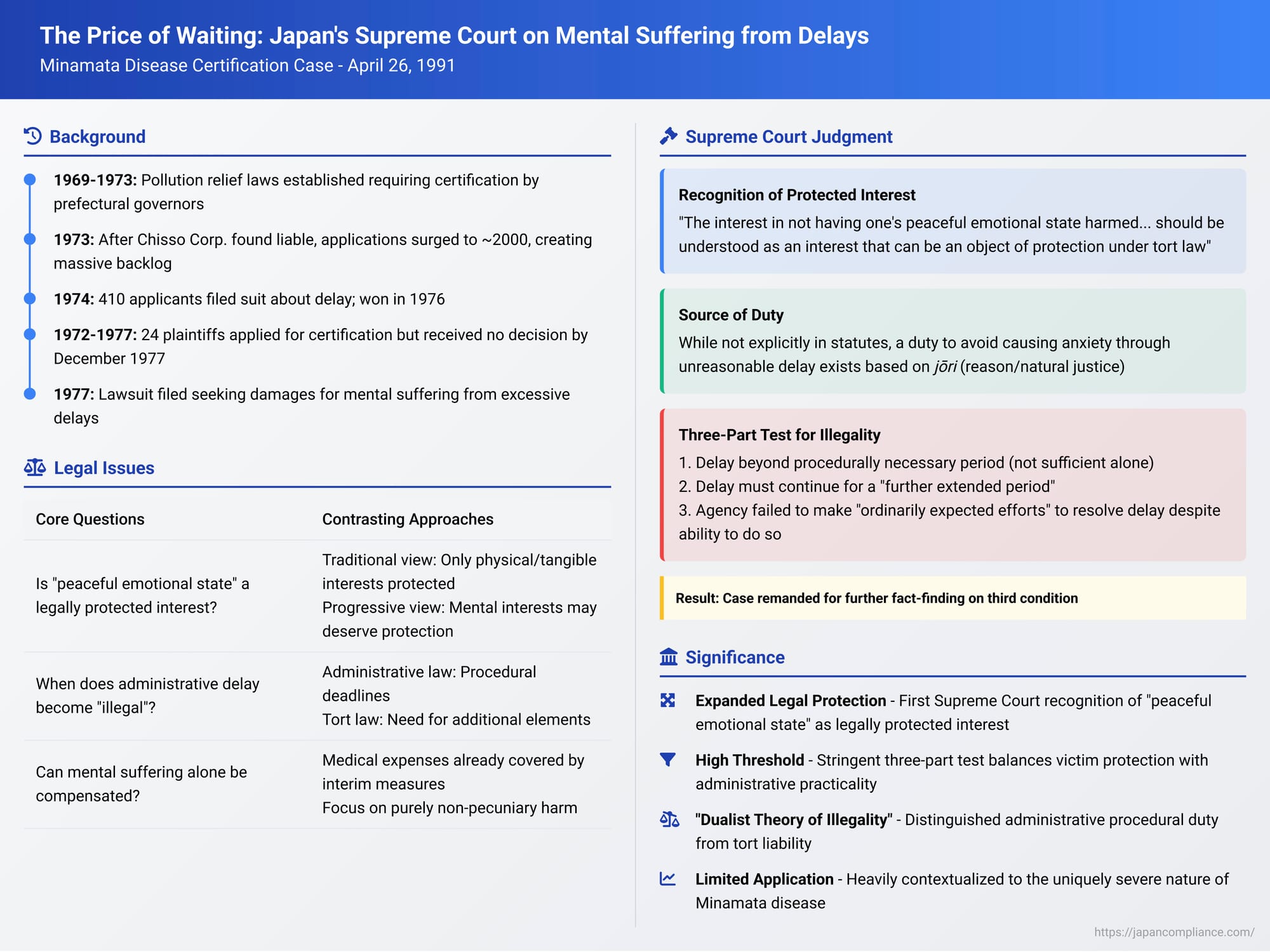

On April 26, 1991, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a pivotal judgment in a case concerning the prolonged delays by the Governor of Kumamoto Prefecture in processing applications for official certification of Minamata disease. This devastating neurological illness, caused by industrial mercury poisoning, had afflicted thousands. The lawsuit was brought by applicants who claimed to have suffered significant mental distress due to the uncertainty and frustration stemming from the extended waiting period for a decision on their certification. The Supreme Court's decision was landmark in two key respects: it recognized that an individual's "peace of mind" or "peaceful emotional state" could, in specific, severe circumstances like those faced by Minamata disease applicants, constitute a legally protectable interest under tort law. Secondly, it meticulously set out a stringent, multi-part test for determining when administrative inaction causing such mental suffering becomes "illegal" for the purposes of state compensation liability. This case remains a crucial reference point for understanding the scope of state responsibility for the non-pecuniary consequences of administrative delays in Japan.

I. The Minamata Disease Certification Backlog and Its Human Cost

The lawsuit arose against the tragic backdrop of the Minamata disease environmental disaster and the subsequent administrative processes established to provide relief to victims.

Legislative Framework for Relief:

Japan had enacted specific legislation to address the health consequences of pollution. The 1969 "Special Measures Act for Relief of Pollution-Related Health Damage" and its successor, the 1973 "Pollution-Related Health Damage Compensation Act" (referred to as the "Compensation Act"), were designed to provide swift relief and financial assistance to victims of designated pollution-related diseases, operating separately from traditional tort law claims against the polluting entities. A critical component of these relief systems was the requirement for individuals to obtain official certification from the relevant prefectural governor confirming that they were indeed suffering from the designated disease. A key feature was that, upon certification, the benefits provided under these acts were typically made retroactive to the date of the individual's application.

The Surge in Minamata Disease Applications and Ensuing Delays:

Minamata disease was one of the primary conditions covered by these statutory relief laws. The scale of the Minamata disaster was immense. Following a landmark Kumamoto District Court ruling on March 20, 1973, which found the polluting company (Chisso Corporation) liable for causing Minamata disease, and subsequent agreements by the company to provide substantial compensation to certified patients, the number of applications submitted to the Governor of Kumamoto Prefecture for official Minamata disease certification surged dramatically. This massive influx of applications overwhelmed the administrative capacity for processing. By 1973, the backlog of unprocessed applications had reportedly reached nearly 2,000, leading to extremely long and distressing delays in the certification process for many individuals who believed they were suffering from the disease.

Prior Litigation on Administrative Inaction:

The severe delays in processing applications had already prompted earlier legal action. In December 1974, a large group of 410 Minamata disease certification applicants filed a lawsuit against the Kumamoto Governor, seeking a court declaration that the governor's failure to process their applications in a timely manner was illegal. This lawsuit was successful, and the judgment of the Kumamoto District Court, issued on December 15, 1976, which found the inaction illegal, subsequently became final and binding. It is noteworthy that some of the plaintiffs involved in the present Supreme Court case (referred to as X) had been among those who had obtained this earlier declaratory judgment.

Interim Administrative Measures for Applicants:

It is also relevant to note that from 1974 onwards, Kumamoto Prefecture had implemented an administrative program known as the "Minamata Disease Certification Applicants Treatment Research Program". Under this program, certain individuals who had applied for certification and met specific criteria were provided with payments for medical expenses. These payments were reportedly roughly equivalent in value to the medical benefits that would have been provided under the statutory relief laws had they been officially certified. This program suggests that some of the direct financial hardship that might have been caused by the certification delays, at least concerning ongoing medical costs, was being administratively addressed for some applicants.

II. The Plaintiffs' Claim for Mental Suffering Due to Delay

The specific case that reached the Supreme Court in 1991 focused directly on the non-pecuniary harm allegedly caused by the administrative delays.

The Plaintiffs (X):

The plaintiffs in this particular lawsuit, X, were a group of 24 individuals. They had all formally applied to the Kumamoto Governor for official certification as Minamata disease patients at various times between December 1972 and May 1977.

The Prolonged Nature of the Delay:

As of December 1977, despite the passage of considerable time since their applications (ranging from several months to over five years for some), none of these 24 applicants had received a formal decision—either certification or rejection—from the Governor regarding their status.

The Lawsuit for Damages for Mental Suffering:

X filed a lawsuit against Y1 (the State of Japan, which had, under the legal framework of agency delegation, entrusted the certification authority to the prefectural governor) and Y2 (Kumamoto Prefecture, as the public entity responsible for the governor's actions and for bearing associated costs). Their claim was for monetary damages, specifically seeking consolation money (isharyō) for the mental suffering they endured as a result of the excessive delay in the processing of their certification applications. This claim was brought under Article 1, paragraph 1 (for state liability for illegal acts of public officials) and Article 3 (for cost-bearing by the public entity) of Japan's State Compensation Act. This type of lawsuit, focusing on compensation for the distress of waiting for an administrative decision, became colloquially known in Japan as an "omatseryō soshō," which can be loosely translated as a "waiting money (or fee/charge) lawsuit".

Lower Court Victories for the Plaintiffs:

Both the Kumamoto District Court, acting as the court of first instance, and subsequently the Fukuoka High Court, on appeal, ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, X. These lower courts found that the State and Kumamoto Prefecture were indeed liable to pay damages for the mental suffering caused by the undue delays in the certification process. It was following these adverse rulings in the lower courts that the defendants, Y1 and Y2, appealed the case to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Judgment: A Two-Part Analysis on Liability for Delay

In its significant judgment of April 26, 1991, the Supreme Court of Japan overturned the decision of the Fukuoka High Court and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court's reasoning was intricate and involved a careful two-part analysis: firstly, it considered whether the type of interest claimed by X—namely, freedom from the anxiety and frustration caused by processing delays—was a legally protectable interest under tort law. Secondly, it delineated the specific conditions under which the Governor's inaction (delay) could be deemed "illegal" for the purposes of a state compensation claim.

A. Part I: Recognizing a Legally Protectable Interest in "Peace of Mind" in the Minamata Context

- The Unique Suffering and Desires of Minamata Disease Applicants: The Supreme Court began its analysis by acknowledging the exceptionally distressing context faced by individuals applying for Minamata disease certification. It stated: "Applicants for certification in this case, suspected of suffering from Minamata disease, known as an intractable illness with unique symptoms, would await a disposition with a keen desire to be liberated as soon as possible from their unstable status of merely being suspected of having the disease. Therefore, the feelings of anxiety and frustration they would harbor due to a prolonged delay by the disposition agency harm their, so to speak, peaceful emotional state (naishin no heion na kanjō), the degree of which is by no means small, and it can be inferred that this is a uniquely profound type of suffering not seen in applicants involved in other, more ordinary administrative certification procedures".

- General Principle Regarding the Legal Protection of "Peaceful Emotional State": The Court then articulated a broader, more general principle concerning the legal protection of an individual's emotional well-being from harm caused by others in society. It opined: "Generally, in modern society where individual values have diversified and various forms of mental friction have emerged, it is necessary for each individual to sufficiently harmonize their own actions with the social activities of others. Therefore, even if a person in social life suffers mental distress due to their peaceful emotional state being harmed by another, it should be said that this must be tolerated to a certain extent. However, for harm that, by prevailing societal standards, is deemed to exceed that limit, there are cases where it should be legally protected as a personal interest. If there is an infringement upon such a protected interest, then depending on the mode and degree of that infringement, there is room for a tort (unlawful act) to be established".

- Application to the Specific Case of Minamata Applicants: Applying this general principle to the specific circumstances of the Minamata disease applicants, the Supreme Court concluded: "The expectation of applicants for certification to be promptly freed from the unstable status of being suspected of suffering from Minamata disease by an early disposition, and the interest in not being made to harbor feelings of frustration and anxiety that lie behind that expectation, should be understood as an interest in not having one's peaceful emotional state harmed. It is appropriate to understand that this interest can be an object of protection under tort law".

B. Part II: Defining When Inaction Becomes "Illegal" for State Compensation Purposes

Having established that the Minamata applicants' interest in their "peace of mind" was, in principle, legally protectable, the Supreme Court then turned to the critical question of determining the conditions under which the Governor's delay in making a disposition would become "illegal" for the purposes of a state compensation claim under Article 1 of the State Compensation Act.

- Distinction from the Administrative Procedural Duty to Act: The Court first drew an important distinction. It acknowledged that under the relevant statutes (the Relief Act and the Compensation Act), a governor who receives a certification application undoubtedly has an administrative procedural duty to process that application promptly and properly. Correspondingly, applicants have a procedural right to receive such a timely and proper disposition.

- However, the Supreme Court clarified that "this duty of action owed by the Governor [under administrative procedure law] is not directly aimed at the protection of the private interest of applicants in not having their peaceful emotional state harmed. Therefore, it cannot be said that this administrative procedural duty of action immediately corresponds to the latter interest [i.e., the private interest in peace of mind], and this requires separate consideration".

- The Court also specifically addressed the earlier, finalized declaratory judgment (which some of the plaintiffs X had obtained) that had found the Governor's inaction to be illegal from an administrative law perspective. The Supreme Court clarified that this prior judgment merely confirmed a breach of the Governor's administrative procedural duty to make a disposition by the time of that earlier judgment's oral arguments; it did not, in itself, automatically establish an illegal infringement of the applicants' private interest in their "peaceful emotional state" for the purposes of a subsequent tort claim for damages. This distinction is seen by many legal scholars as an endorsement by the Supreme Court of the "dualist theory of illegality" (ihōsei nigen-ron). This theory posits that the concept of "illegality" sufficient for an administrative revocation suit or a suit confirming the illegality of inaction can be different from, and not necessarily coextensive with, the concept of "illegality" required to establish a claim for damages under the State Compensation Act, which generally requires a more direct infringement of a private right or interest.

- A Duty of Care Based on "Jōri" (Reason or Natural Justice) to Protect Peace of Mind: Even though the specific statutes (Relief Act, Compensation Act) did not explicitly create a duty for the Governor to act within a specified timeframe for the direct purpose of protecting the applicants' peace of mind, the Supreme Court found that such a duty could nonetheless be derived from "jōri". "Jōri" is a Japanese legal concept that refers to inherent reason, natural justice, sound principles of law, or societal common sense. The Supreme Court reasoned as follows: "Generally, it is a matter of course that a disposition agency should dispose of a certification application within a reasonable period. If a disposition is not made for an unreasonably long period, it is easily foreseeable that applicants who were expecting an early disposition will harbor feelings of anxiety and frustration, leading to harm to their peaceful emotional state. Therefore, it can be said that the disposition agency has a duty of action based on jōri to avoid such a result". The Supreme Court's reliance on the somewhat general concept of jōri here is a logical consequence of its earlier step of having defined the protected interest itself as the rather general "peaceful emotional state".

- Stringent Three-Part Test for Breach of the Jōri-Based Duty (and thus, for Illegality): Having established this jōri-based duty of care, the Supreme Court then set out a strict, three-part conjunctive test that must be satisfied to determine when a disposition agency (like the Governor in this case) could be said to have breached this duty, thereby rendering its inaction illegal for the purposes of a state compensation claim for mental suffering:

- "It is not sufficient merely that the disposition agency objectively failed to make a disposition within the period that is considered procedurally necessary for that disposition". This implies that simply exceeding a standard processing time, by itself, does not automatically equate to compensable illegality.

- "The delay must continue for a further extended period when compared to that [procedurally necessary] period". This introduces a requirement for a significantly protracted delay beyond ordinary administrative tardiness.

- "And, during that [further extended] period, it must have been possible for the disposition agency, through efforts that would ordinarily be expected of it, to resolve the delay, but it failed to exhaust such efforts to avoid it". This element essentially introduces a fault or negligence-like component, requiring an assessment of whether the agency could have, with reasonable diligence, overcome the backlog or processing difficulties but failed to do so.

Remand for Further Factual Findings:

- The Supreme Court found that the Fukuoka High Court, in its previous judgment finding for the plaintiffs, had not adequately determined the facts necessary to properly apply this newly articulated three-part test, particularly concerning the crucial third condition—that is, whether the Kumamoto Governor, despite the massive influx of Minamata disease applications and other acknowledged administrative challenges, could indeed have resolved the processing delays with "ordinarily expected efforts."

- The Supreme Court emphasized that assessing this third condition requires a comprehensive and concrete consideration of various specific factors, including "the total number of certification applications pending at the time, the capacity of the administrative organs and personnel responsible for conducting medical examinations and reviews, the content and operational methods of these processes, and the degree of cooperation (or lack thereof) from the applicants' side".

- Because the High Court had not made sufficient findings on these critical factual matters necessary for a proper application of the legal standard, the Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment (insofar as it had found in favor of the plaintiffs and awarded damages) and remanded the case back to the Fukuoka High Court. The purpose of the remand was for further deliberation and specific fact-finding in line with the legal standard and the three-part test now clearly articulated by the Supreme Court.

- It is important to note that upon remand, the Fukuoka High Court ultimately ruled against the plaintiffs, finding that the stringent third condition of the Supreme Court's test (i.e., a failure by the Governor to make ordinarily expected efforts to resolve the delay, despite the possibility of doing so) was not met on the evidence. This subsequent High Court decision, which denied liability, was later appealed to the Supreme Court again, which then upheld the denial of liability, effectively ending the plaintiffs' claim for compensation in this specific "waiting money" lawsuit.

IV. Legal Commentary and Lasting Impact

The Supreme Court's 1991 decision in the Minamata disease certification delay case, often referred to as the "Omatase-chin Soshō" or "waiting money lawsuit", has had a profound and lasting impact on Japanese administrative law and tort law, particularly concerning state liability for non-pecuniary harm caused by administrative inaction.

The Novelty of Claiming for "Waiting Money" and the Focus on Mental Suffering:

- A distinctive feature of this case was its primary focus on claiming compensation for mental suffering (solatium or consolation money) arising specifically from the delay in administrative processing, rather than from a substantively incorrect administrative decision or from a direct physical injury caused by a state act. Prior lawsuits against the state alleging harm from administrative delays had typically sought compensation for tangible financial or property losses that resulted from such delays. In the Minamata context, however, specific administrative measures were already in place to provide payments for medical expenses to applicants awaiting certification. This meant that, as the Supreme Court itself acknowledged in its judgment, direct financial losses due to the delay in certification were, for many applicants, "almost resolved" or at least substantially mitigated. This unique factual background shifted the legal battleground squarely onto the less tangible but equally real harm of anxiety, frustration, and the prolonged uncertainty endured by the applicants.

The Judicial Expansion of Legally Protected Personal Interests:

- The Supreme Court's explicit recognition in this case that an individual's "interest in not having one's peaceful emotional state harmed" could, under certain severe circumstances, qualify as a legally protectable interest under tort law was a very significant jurisprudential development. This decision aligned with a broader, albeit cautious, trend in Japanese case law during that period, which showed a willingness to expand the range of personal interests (人格的利益 - jinkakuteki rieki) that could receive legal protection from tortious infringement. The commentary cites, as another example of this trend, a Supreme Court case that recognized an "interest in having one's name correctly pronounced."

- However, the commentary also provides a critical caveat: the Supreme Court's reasoning in this Minamata "waiting money" case was heavily reliant on the exceptionally severe and unique nature of Minamata disease itself, the profound and life-altering uncertainty faced by those who suspected they were afflicted, and the consequent "uniquely profound" nature of the emotional distress they experienced during the prolonged waiting period. This strong emphasis on the specific, extreme circumstances of the Minamata applicants means that the direct applicability of this "peaceful emotional state" protection as a precedent for claiming damages for delays in other, more routine or less dire, administrative certification processes would require further careful judicial consideration and would likely depend heavily on the specific facts and the nature of the interests at stake in those other contexts.

The Dissenting View on the Scope of Compensable Mental Suffering:

- It is important to note that the Supreme Court's judgment was not unanimous. It highlights a dissenting opinion from Justice Kagawa, who advocated for a more restrictive interpretation of the provisions of the Japanese Civil Code (specifically Articles 709 and 710) that govern general tort liability, particularly concerning compensation for mental suffering. The dissenting justice argued that the Civil Code primarily aims to provide redress for pecuniary (i.e., financial or property-related) losses. From this perspective, compensable mental suffering should be limited to cases involving the infringement of core, well-established personal interests such as physical integrity (harm to the body), liberty, or honor, and even then, damages should only be awarded to an extent deemed socially tolerable. According to this dissenting view, an "interest in not having one's peaceful emotional state harmed" was considered too general, too abstract, and too subjective to qualify as an independent, legally protectable interest under established tort principles. The dissent further suggested that the kind of anxiety experienced by the Minamata applicants, which would ostensibly be resolved by any disposition (whether it be certification or rejection of the application), fell outside the scope of what tort law should legitimately compensate.

- While the majority view in Japanese legal scholarship and prevailing case law tends to interpret Civil Code Article 710 (which explicitly mentions compensation for non-pecuniary harm) as an illustrative rather than an exhaustive provision—thereby confirming that tort law can, in principle, compensate for a broader range of mental suffering—the concerns raised by the dissenting opinion about the potential for an undue or unmanageable expansion of state liability are pertinent and worthy of consideration. The majority in this Supreme Court decision, however, appeared to address this inherent risk of over-expansion not by narrowly defining the scope of the protectable interest itself, but rather by establishing a very strict and demanding set of conditions that must be met before the state's inaction could be deemed illegal and thus compensable.

The Stringent Three-Part Test for Establishing Illegality:

- The Supreme Court's formulation of the three specific conditions that must be met to establish a breach of the jōri-based duty to avoid causing mental suffering through administrative delay is notably stringent. The first of these conditions (the objective failure of the disposition agency to make a disposition within the period considered procedurally necessary for that disposition) essentially relates to establishing a breach of the underlying administrative procedural duty to act in a timely manner. The third condition (the failure of the disposition agency to make ordinarily expected efforts to resolve the delay, despite having had the possibility of doing so) closely resembles the requirement of proving negligence or fault on the part of the administrative authority.

- The truly distinctive and perhaps most challenging element for plaintiffs to satisfy in future cases is the second condition: the requirement that the delay must have continued for a "further extended period" beyond what was merely procedurally necessary. The precise legal rationale or justification for this "added period" as a distinct and separate requirement for establishing illegality has been a subject of some academic critique, as it might appear to impose an extra, and perhaps ill-defined, hurdle for plaintiffs beyond demonstrating unreasonable delay and administrative negligence. However, one plausible interpretation, also mentioned in the commentary, is that this requirement of a "further extended period" of suffering might be understood as a threshold mechanism. It could be seen as the Court's way of identifying when the infringement of the rather general "peaceful emotional state" becomes sufficiently severe, prolonged, and socially intolerable to warrant legal protection and monetary compensation under tort law, distinguishing it from the more ordinary frustrations and anxieties that might accompany typical administrative processes.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's April 26, 1991, decision in the Minamata disease certification delay case, often referred to as the "Omatase-chin Soshō" or "waiting money lawsuit," stands as a profoundly significant judgment in the annals of Japanese administrative law and tort law. It courageously acknowledged that prolonged and unreasonable delays in crucial administrative processing, particularly in contexts as uniquely dire and distressing as the Minamata disease certifications, can indeed cause profound mental suffering. For the first time at the Supreme Court level, it recognized that this suffering, characterized as an infringement of one's "peaceful emotional state," could constitute a legally compensable harm.

However, while opening this important door for redress, the Supreme Court also, with considerable caution, set a very high and stringent bar for establishing the state's liability in such cases. The complex three-part test it articulated—requiring not only unreasonable delay beyond what is procedurally necessary but also a "further extended period" of such delay, coupled with a demonstrable failure by the administrative authorities to make "ordinarily expected efforts" to resolve the backlog—makes successfully pursuing such claims a challenging endeavor for plaintiffs.

The case ultimately underscores the judiciary's delicate and ongoing balancing act: on one hand, the imperative to provide a meaningful path for redress for genuine and severe suffering caused by administrative failures or systemic inertia; and on the other hand, the need to protect public authorities from an overly broad or unmanageable scope of liability for delays that may, in some instances, arise from complex, large-scale, and resource-intensive administrative tasks. This 1991 judgment remains a key, and much-discussed, precedent in understanding the evolving scope of state responsibility for the non-pecuniary consequences of administrative inaction in Japan.