The Price of Silence: Japanese Supreme Court on Seller's Duty to Disclose Future Discount Plans and Emotional Distress Damages

Date of Judgment: November 18, 2004

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, 2004 (Ju) No. 482 – Claim for Damages

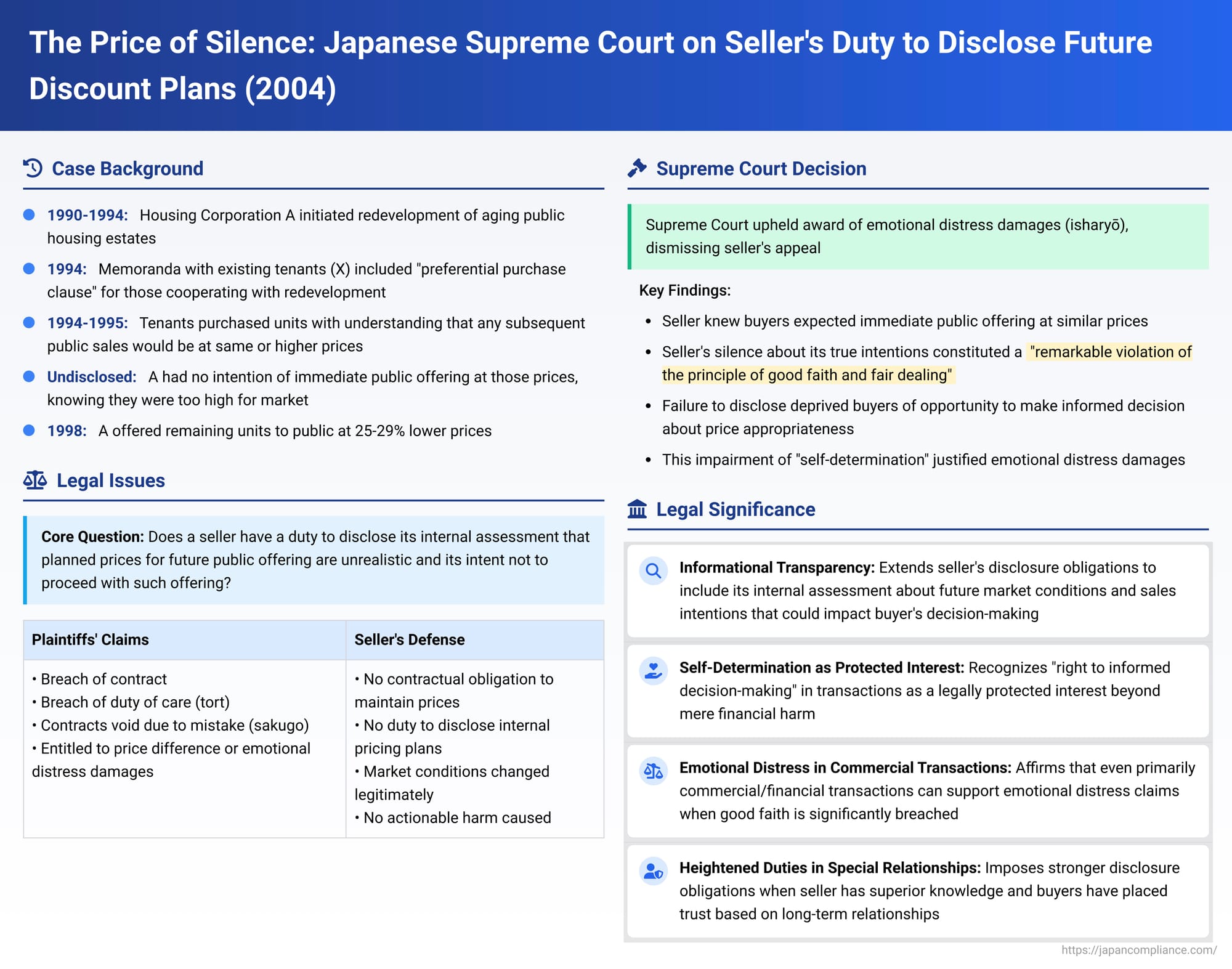

In the complex world of real estate transactions, particularly during volatile market conditions, the information held by a seller regarding its future sales strategies can be of critical importance to a buyer. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 18, 2004, addressed a situation where a public entity, having sold condominium units to prior tenants under a preferential scheme, later offered remaining units to the general public at significantly lower prices without having disclosed its intentions to the initial buyers. The Court's ruling affirmed an award for emotional distress damages, not for the price difference, but for the seller's breach of its good faith duty to provide information necessary for the buyers to make a fully informed purchasing decision.

Background: Redevelopment Promises and a Shifting Market

The case originated in 1990 when "A" (the former Housing and Urban Development Corporation, whose obligations were later succeeded by "Y," the appellant) initiated redevelopment projects for aging public housing estates in Chiba and Kanagawa prefectures. To facilitate this large-scale undertaking, A entered into memoranda with the existing tenants of these estates, including "X and others" (the plaintiffs/respondents), by 1994. A key component of these memoranda was a "preferential purchase clause." This clause stipulated that tenants who cooperated with the redevelopment—for example, by vacating their old units by a specified date—would be given priority to purchase newly built condominium units in the redeveloped estates before these units were offered to the general public.

X and others, relying on this arrangement, understood two crucial things: first, that a general public offering of any remaining units would occur immediately after their preferential purchase opportunity; and second, that the price for units in this general public offering would be at least equivalent to the price at which they were purchasing their units. Based on this understanding and their cooperation with the redevelopment, X and others entered into sales contracts with A to purchase their new condominium units in 1994 and 1995.

However, A harbored a different internal assessment and intention. A was aware that the prices set for X and others were relatively high given the prevailing real estate market conditions (Japan's "bubble economy" had burst in the early 1990s, leading to falling property values). A also recognized that if it attempted to sell the remaining units to the general public at these same high prices, there would likely be no interested buyers. Consequently, A had no actual intention of making an immediate public offering of the unsold units at those prices following the sales to X and others. Critically, A did not disclose this lack of intention or its assessment of the market situation to X and others at the time they were making their purchase decisions.

Several years passed. Then, in 1998, A made a general public offering for the remaining unsold units in the redeveloped estates. The prices in this public offering were substantially lower than what X and others had paid. The average price reduction was approximately 25% for the Chiba estate (c-danchi) and about 29% for the Kanagawa estate (d-danchi) compared to the prices X and others had committed to.

The Legal Battle: From Financial Claims to Emotional Harm

Feeling aggrieved, X and others sued Y (as A's successor). Their primary claims were for breach of contract or tort, seeking compensation for the financial loss equivalent to the price difference. They also argued, alternatively, that their purchase contracts were void due to fundamental mistake (sakugo) regarding the sales conditions.

The District Court (Tokyo District Court, judgment February 3, 2003) rejected the claims for breach of contract (in terms of direct financial compensation for the price difference) and also denied that there was a legally significant mistake that would void the contracts. However, the District Court did find that A had breached a duty of care owed to X and others. Specifically, it held that A, under the principle of good faith and fair dealing (shingi-soku), had an obligation to explain to X and others at the time they were signing their contracts that A did not, in fact, intend to make an immediate public offering of the remaining units. For this breach of the duty to explain, the District Court awarded X and others damages for emotional distress (isharyō).

Both X and others (presumably dissatisfied with not receiving the full price difference) and Y appealed to the Tokyo High Court. The High Court (judgment December 18, 2003) dismissed both appeals, upholding the District Court's decision. Y then sought and obtained acceptance of its appeal to the Supreme Court, challenging the award of emotional distress damages.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Affirming Liability for Infringed Self-Determination

On November 18, 2004, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued its judgment, dismissing Y's appeal and thereby upholding the award of emotional distress damages to X and others.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- A's Awareness of Buyers' Expectations: A could have, at the very least, easily known that X and others, due to the nature of the preferential purchase clause and the context of their cooperation, held a firm expectation that any subsequent public offering of unsold units would happen immediately and at prices no lower than what they were paying.

- Failure to Disclose True Intentions: Despite this awareness, A completely failed to explain to X and others that it had no intention of making such an immediate public offering at comparable prices because it knew those prices were too high for the general market.

- Deprivation of Informed Decision-Making: This failure to disclose critical information deprived X and others of the opportunity to fully and properly consider the appropriateness of the price A was asking them to pay. They were prevented from making a truly informed decision about whether or not to enter into their purchase contracts under the terms presented.

- "Remarkable Violation" of Good Faith: The Supreme Court characterized A's failure to provide this explanation as a "remarkable violation of the principle of good faith and fair dealing" .

- Justification for Emotional Distress Damages: Consequently, the Court concluded that even though the decision-making process (whether to sign the purchase contracts) pertained to financial interests, A's aforementioned conduct constituted an illegal act of a nature that could justify recognizing a claim for emotional distress damages (isharyō). The Supreme Court found its decision did not conflict with a previous ruling (Supreme Court, December 9, 2003, Minshu 57-11-1887) which had been more restrictive about awarding isharyō for breach of explanation duty in certain transactional contexts, implying the facts or severity in the present case were distinguishable.

The Duty to Explain and "Infringement of Self-Determination"

This 2004 Supreme Court judgment is significant because it affirmed an award of emotional distress damages stemming from a breach of the duty to explain in a commercial transaction where the most apparent "loss" was financial (paying a higher price). The core of the recognized injury was not the price difference itself, but the infringement of the buyers' opportunity to make a free and informed decision – sometimes referred to as an "infringement of the right to self-determination" in a transactional context.

The commentary accompanying the case explores the nuances of this concept:

- Traditional Context: Typically, damages for infringement of self-determination (particularly isharyō) had been recognized in contexts like medical malpractice, where a doctor's failure to provide adequate explanation deprived a patient of the ability to make informed choices about their own body and medical treatment.

- Transactional Context - Divergent Views:

- One perspective argues that the right to self-determination is a fundamental interest, and its infringement—the loss of an opportunity to make an informed choice—constitutes a compensable harm in itself, regardless of whether there is a tangible financial loss or if the context is personal (like health) or transactional. Under this view, even if the property value had increased after purchase (meaning no financial loss), the buyers might still have a claim for isharyō due to the way their decision-making was impaired.

- A more cautious approach suggests that in purely transactional settings, claims of "infringed self-determination" can sometimes be a way of seeking compensation for financial losses that are otherwise hard to recover. This view urges prudence in extending isharyō claims, suggesting they should be reserved for cases where there is genuine non-pecuniary harm distinct from financial loss, or where the defendant's conduct is particularly blameworthy (e.g., involving deceit or exploitation of vulnerability). The commentary notes that in cases of investment products sold without adequate explanation, if financial losses are compensated, a separate award for isharyō might not always be necessary. However, it also acknowledges that situations like losing one's life savings for retirement through deceptive sales practices could warrant isharyō beyond mere financial restitution.

In the present case, the Supreme Court's emphasis on A's conduct being a "remarkable violation" of good faith suggests that the severity of the breach played a key role in justifying the isharyō award. While the decision involved financial considerations, the Court focused on the impairment of the decision-making process itself concerning the "appropriateness of the price".

Legal Framing and Alternative Claims

The Supreme Court upheld the award based on tort liability for the breach of the duty to explain. However, the underlying facts of the case touch upon other areas of contract law:

- Mistake (Sakugo): X and others had initially argued that their contracts were void due to mistake. While the District Court denied this (based on a mistake regarding the appropriateness of the price), the commentary suggests that the mistake could also be framed as being about the fundamental "premise" that an immediate public sale at a similar price would occur. Such a premise, given the Memoranda and the ongoing relationship, could potentially be considered part of the foundation of the contract. (The rules on mistake in the Japanese Civil Code were significantly revised in 2017, so future cases would be analyzed under the new provisions ).

- Fraud or Misrepresentation: Although not the basis of the final judgment, the commentary notes that facts like these could also support arguments of fraud by silence or misrepresentation, especially concerning consumer contract law principles about providing definitive judgments on uncertain future matters.

The overlap is natural: a failure to explain can lead to a party forming an incorrect understanding (mistake) or being misled (akin to fraud), thereby impairing their ability to give truly informed consent to a contract. The choice of legal framing (tort, mistake, fraud) can have different implications for proof and remedies.

Implications for Business and Sellers

This Supreme Court decision sends a clear message to sellers, particularly institutional ones or those in a position of informational power dealing with individuals who have placed trust in them:

- Transparency in Sales Plans: When prior agreements or specific circumstances create reasonable expectations in buyers about future sales activities (like pricing or timing of public offerings), sellers have a heightened duty to be transparent. Materially misleading silence about actual intentions can breach good faith.

- Informed Decision-Making: The opportunity for a buyer to make a fully informed decision is a legally protected interest. Depriving a buyer of this, especially through a significant breach of good faith, can lead to liability.

- Risk of Emotional Distress Damages: Even in primarily commercial or financial transactions, egregious breaches of the duty to explain can result in awards for emotional distress, not just direct financial compensation. This is particularly relevant if the conduct is deemed a "remarkable violation" of good faith principles.

- Context Matters: The long-term relationship stemming from the redevelopment agreements and the tenants' cooperation likely amplified the seller's duty of care and the buyers' reliance.

Conclusion: The Value of an Informed Choice

The 2004 Supreme Court ruling underscores that the duty of good faith in contractual negotiations and performance in Japan is not a mere platitude. It can impose concrete obligations on sellers to disclose information that is vital to a buyer's ability to assess a transaction fairly. While courts may be hesitant to simply compensate for market-driven price differences after a sale, this case demonstrates that a significant and blameworthy failure to provide crucial information – thereby undermining the buyer's ability to make an informed choice – can be recognized as a distinct legal wrong justifying an award for emotional distress. It highlights that the integrity of the decision-making process itself has value, and its impairment through a serious breach of good faith can give rise to a claim for non-pecuniary damages.