The Price of Silence: A Public Corporation's Duty to Explain and Damages for Lost Opportunity in Japanese Housing Sales

Judgment Date: November 18, 2004

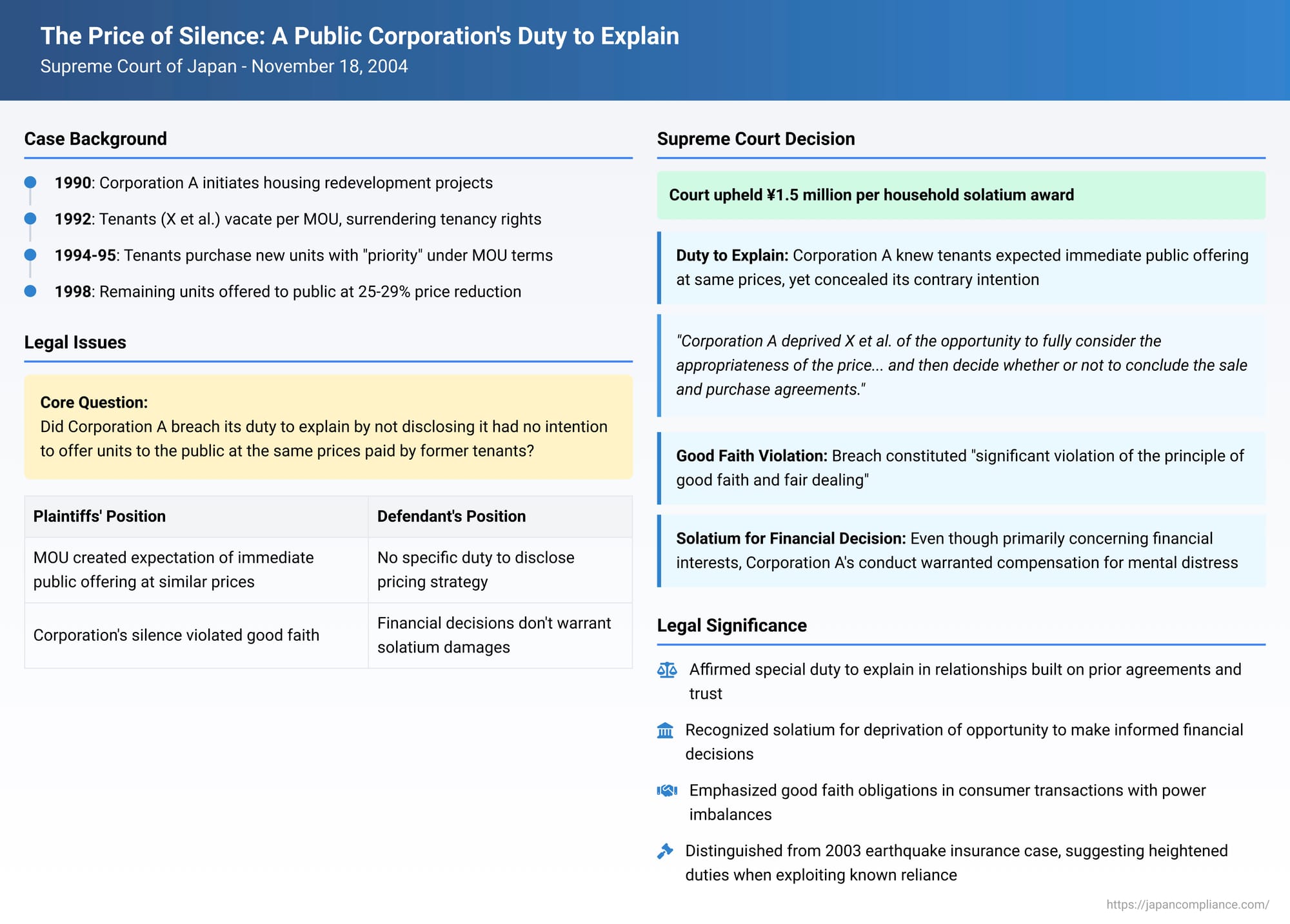

In a significant ruling that underscores the importance of good faith and transparency in contractual dealings, particularly when a party is induced to alter its position based on specific undertakings, Japan's Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, delivered its judgment on November 18, 2004 (Heisei 16 (Ju) No. 482). The case involved former tenants of public housing complexes who cooperated with a redevelopment project managed by the Housing and Urban Development Corporation (hereinafter "Corporation A"). The core issue was Corporation A's failure to disclose crucial information about its pricing strategy for redeveloped units, leading to claims for damages by the former tenants who purchased units at prices significantly higher than those later offered to the general public. This decision is notable for affirming a breach of the duty to explain and, importantly, for awarding solatium (damages for mental distress) for the infringement of the plaintiffs' opportunity to make an informed financial decision.

The Redevelopment Project: Promises Made, Trust Placed

Around 1990, Corporation A initiated redevelopment projects for two of its housing estates: Housing Complex A in Kashiwa City, Chiba Prefecture, and Housing Complex B in Yokohama City. The plaintiffs in this case, referred to as X et al., were tenants residing in these complexes.

To facilitate the redevelopment, Corporation A entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the tenants, including X et al. This MOU stipulated that if the tenants cooperated with the redevelopment—primarily by agreeing to terminate their existing lease contracts and vacate their premises by specified deadlines (September 30, 1992, for Housing Complex A, and March 31, 1992, for Housing Complex B)—Corporation A would provide certain benefits. These included:

- An opportunity to purchase units in the redeveloped housing complexes with priority before they were offered to the general public.

- Provision of temporary housing until the new units were completed.

- Payment of relocation expenses and an additional sum of ¥1 million.

Central to the dispute was the "Priority Purchase Clause" within this MOU. This clause stated that Corporation A would "mediate" the sale of redeveloped units to the cooperating tenants with priority before any public offering. The Supreme Court interpreted this clause as being predicated on several key assumptions:

- That a public offering of any units remaining unsold after the priority sales to tenants like X et al. would occur immediately thereafter.

- That the price offered to the general public would be at least equivalent to the price at which the units were offered to X et al.

- That X et al. would be able to secure a unit without having to participate in a lottery, effectively guaranteeing them a home in the redeveloped complex if they chose to purchase.

Relying on these commitments, X et al. duly cooperated with Corporation A, vacated their homes by the agreed-upon deadlines, and thereby surrendered their existing tenancy rights.

The Sales Contracts and Corporation A's Undisclosed Intentions

Following the redevelopment, X et al. proceeded to purchase units in the new complexes. Plaintiffs No. 1 through 43 signed sale and purchase agreements for units in the newly built Housing Complex C (the redeveloped Housing Complex A) on October 31, 1995. Plaintiffs No. 44 through 58 signed agreements for units in Housing Complex D (the redeveloped Housing Complex B) on December 10, 1994.

At the time X et al. entered into these contracts, they reasonably believed, based on the Priority Purchase Clause in the MOU, that the prices they were paying were fair and stable, expecting that any imminent public offering would be at similar or potentially higher prices.

However, Corporation A held a different internal assessment and intention. After the priority sales to X et al. and to cooperating residents of other redevelopment projects (an interim step which yielded no sales for the remaining 83 units in Complex C and 46 units in Complex D), Corporation A recognized that the prices at which units had been offered to X et al. were too high to attract buyers from the general public. Consequently, at the time of concluding the sale contracts with X et al., Corporation A had no intention of making an immediate public offering of the unsold units at those prevailing prices.

Crucially, Corporation A did not disclose this lack of intention to X et al. when they were making their purchasing decisions.

The Aftermath: Unexpected Price Drops and Legal Recourse

It was not until July 25, 1998—nearly three to four years after X et al. had purchased their units—that Corporation A made a general public offering of the remaining 83 units in Housing Complex C and 46 units in Housing Complex D. These units were offered at substantially reduced prices. The average price reduction was 25.5% for Complex C (an average decrease of approximately ¥8.54 million per unit) and 29.1% for Complex D (an average decrease of approximately ¥16.31 million per unit).

Feeling betrayed by this outcome, which they perceived as a breach of the spirit and implicit terms of the MOU, and having suffered a de facto financial disadvantage, X et al. initiated legal proceedings. Their claims against Corporation A's successor (Corporation A was dissolved in 1999, its rights and obligations passing to Corporation B, which was subsequently dissolved in 2004, with its rights and obligations inherited by Y', the Urban Renaissance Agency, the appellant in this Supreme Court case) included breach of the MOU, invalidity of the sale contracts due to error (mistake), violation of a duty to set appropriate prices, and breach of a duty to explain.

The Tokyo District Court, as the court of first instance, dismissed most of these claims but found in favor of X et al. on the ground of a breach of the duty to explain. It held that Corporation A, based on the principle of good faith, had an obligation to inform X et al. at the time of their purchase that it was not then planning an immediate public offering of the remaining units. While the court did not award damages for direct financial loss stemming specifically from this failure to explain, it acknowledged the significant mental distress caused to X et al. by this lack of transparency and awarded each household ¥1.5 million as solatium. The Tokyo High Court upheld this decision, leading to Y's appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Affirming Duty and Awarding Solatium

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' finding of liability for breach of the duty to explain and the award of solatium.

The Court meticulously recounted the factual background, emphasizing:

- X et al.'s cooperation in the redevelopment by surrendering their tenancy rights.

- The nature of the Priority Purchase Clause in the MOU, which presupposed an immediate public offering at comparable prices and guaranteed X et al. units without a lottery.

- X et al.'s resultant understanding at the time of their purchase that such an immediate and comparably priced public offering would follow.

- Corporation A's contemporaneous knowledge that its prices to X et al. were too high for the general market and its lack of intention to make an immediate public offering at those prices.

- Corporation A's complete failure to explain this lack of intent to X et al.

Based on these points, the Supreme Court reasoned that Corporation A could have, at the very least, easily recognized X et al.'s understanding derived from the Priority Purchase Clause. By failing to disclose its true intention—that it did not plan an immediate public offering at those prices because it knew they were uncompetitively high—Corporation A effectively "deprived X et al. of the opportunity to fully consider the appropriateness of the price of the condominium units set by Corporation A and then decide whether or not to conclude the said sale and purchase agreements."

The Court characterized this failure to explain as a "significant violation of the principle of good faith and fair dealing." Furthermore, it held that even though the decision-making process of X et al. primarily concerned financial interests (the purchase of property), Corporation A's conduct was "an illegal act that can affirm the generation of a right to claim solatium."

The Supreme Court also explicitly stated that this judgment did not conflict with a precedent cited by the appellant (Supreme Court, December 9, 2003, concerning an insurer's duty of explanation regarding earthquake insurance). This earlier case had denied solatium for a breach of explanation duty related to a financial decision. The present case was distinguishable, likely due to the more egregious nature of Corporation A's omission, particularly in light of the pre-existing MOU which created specific expectations and a relationship of trust. While the 2003 earthquake insurance case involved some explanation, albeit potentially insufficient, the current case involved a complete lack of explanation about a critical deviation from an understanding Corporation A knew the plaintiffs held, an understanding fostered by Corporation A's own prior commitments.

Analyzing the Scope and Basis of the Duty to Explain

The duty to explain affirmed in this case arose from the unique and "special circumstances" created by the MOU. X et al. were not ordinary market participants; they were former tenants who had made significant sacrifices (loss of tenancy rights) in reliance on specific promises from Corporation A regarding their future housing. This established a particular relationship of trust and expectation.

Corporation A's silence was not merely a failure to volunteer information in a standard commercial transaction. It was an omission that directly undermined the basis upon which X et al. had cooperated and were making their purchase decisions. Knowing that X et al. expected an immediate public sale at comparable prices (which would have validated the prices they were paying), Corporation A's failure to disclose its contrary intention was a serious breach of good faith. Had X et al. been informed that Corporation A itself doubted the marketability of the units at those prices and was not planning an immediate public test of those prices, they would have been alerted to potential issues with price appropriateness and could have investigated market conditions more thoroughly, negotiated, or perhaps reconsidered their purchase timing or decision.

While the ruling is heavily fact-dependent, particularly on the existence and terms of the MOU, it underscores a broader principle: a party, especially one in a superior informational position or one that has made prior specific undertakings, may have a heightened duty to disclose information that is critical to the other party's decision-making process, particularly if non-disclosure would exploit a known misunderstanding or contradict previous assurances.

The Significance of Awarding Solatium for Infringement of Financial Decision-Making

Traditionally, solatium in Japanese tort law has been more readily associated with infringements of personal rights such as life, bodily integrity, liberty, or reputation. Awarding solatium for harm related to purely financial decisions has been less common.

This Supreme Court decision is significant for affirming that the deprivation of an opportunity to make a properly informed financial decision, particularly when caused by a serious breach of good faith by the other party, can constitute a legally recognized harm warranting compensation for mental distress. It acknowledges that the integrity of the decision-making process itself, especially in significant transactions fostered by specific prior agreements and trust, is a protected interest. The violation of this interest, through deliberate non-disclosure of critical, price-sensitive information that the seller knew the buyer was relying on, was deemed sufficiently wrongful to justify an award for non-pecuniary damages.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the housing redevelopment case is a vital reminder of the obligations that can arise under the principle of good faith and fair dealing, particularly in complex transactions built upon prior agreements and induced cooperation. It clarifies that a failure to provide critical information, thereby undermining a party's ability to make an informed decision, can constitute a serious breach of duty. Furthermore, it affirms that such a breach, even in a context primarily concerning financial interests, can give rise to a claim for solatium if the conduct is sufficiently egregious and deprives individuals of a fair opportunity to assess their significant financial commitments. This case underscores the value the law places on transactional fairness and the protection of informed consent.