The Price of Renewal: Japanese Supreme Court Upholds (Non-Excessive) Lease Renewal Fees

Date of Judgment: July 15, 2011

Case Name: Claim for Return of Renewal Fee, etc. (Main Suit); Counterclaim for Renewal Fee; Claim for Performance of Guarantee Obligation

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

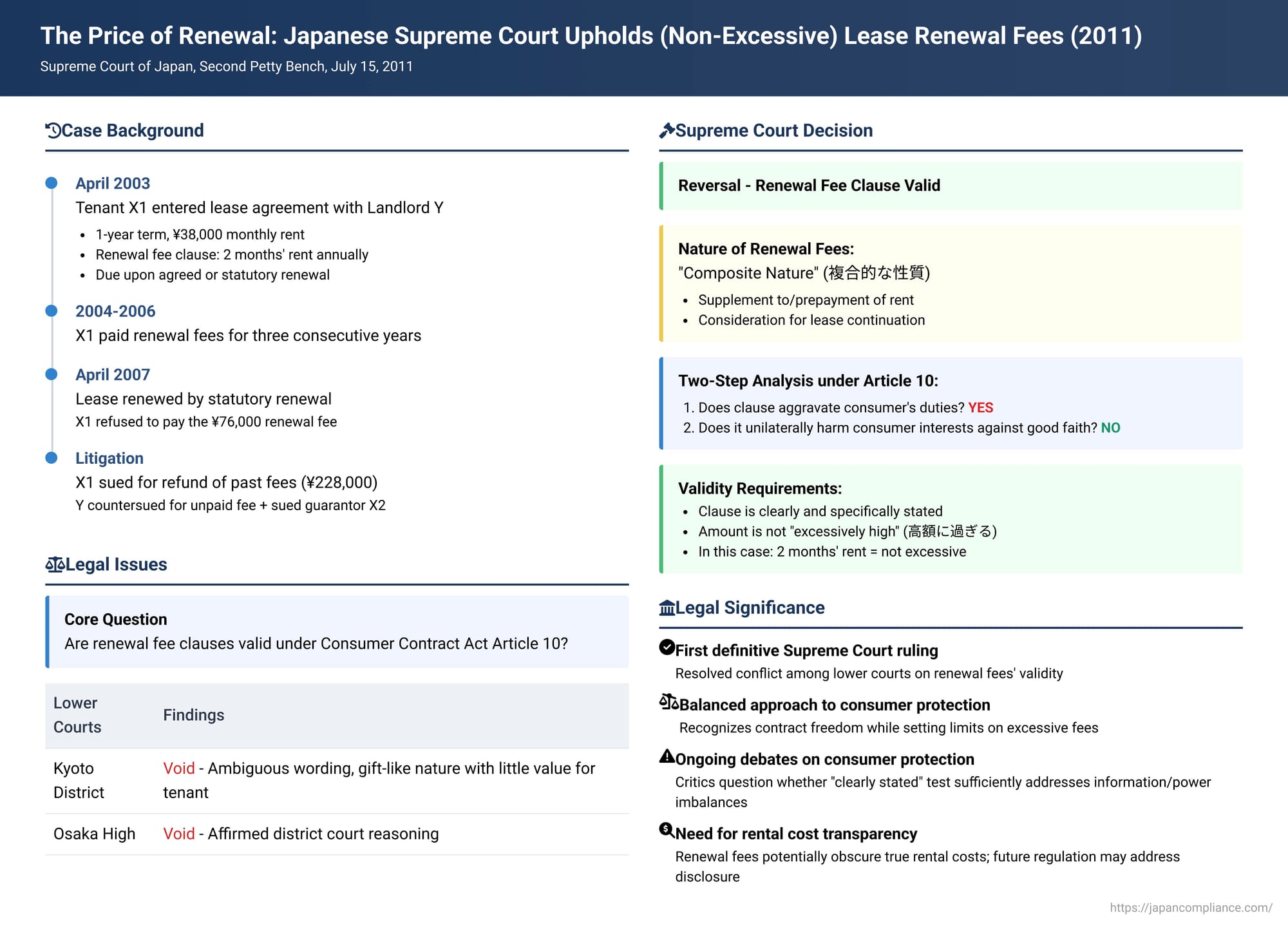

In Japan's rental housing market, particularly in certain regions, tenants often encounter "renewal fees" (更新料 - kōshinryō) – payments made to the landlord upon renewing a lease agreement. For years, the legal status of these fees, especially in light of consumer protection laws, was a subject of debate and varying lower court judgments. On July 15, 2011, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision, providing much-anticipated guidance on the validity of renewal fee clauses in residential lease agreements.

The Lease, The Fees, The Dispute

The case brought before the Supreme Court involved the following circumstances:

- The Lease Agreement: On April 1, 2003, X1 (the tenant) entered into a lease agreement with Y (the landlord) for an apartment in Kyoto. The lease term was one year, with a monthly rent of ¥38,000. The agreement included a specific "Renewal Fee Clause."

- The Renewal Fee Clause: This clause stipulated that:

- Upon renewal of the lease agreement, whether by mutual agreement or by statutory (automatic) renewal, X1 was required to pay Y a renewal fee equivalent to two months' rent. This payment was due annually upon each one-year renewal.

- The landlord, Y, would not refund or make any adjustments to the renewal fee, regardless of the actual length of X1's occupancy.

- Payments and Subsequent Non-Payment: X1 paid the renewal fee and renewed the lease by agreement from 2004 through 2006. However, when the lease was subsequently renewed effective April 1, 2007 (this time through statutory renewal, based on X1's continued use of the premises after the term ended), X1 did not pay the renewal fee.

- Legal Action: X1 initiated a lawsuit against Y, seeking a refund of the renewal fees already paid (¥228,000 in total for three renewals) and a court declaration that no obligation existed to pay any outstanding renewal fees. Y, in response, filed a counterclaim against X1 for the unpaid renewal fee of ¥76,000. Y also sued X2, who was the joint guarantor for X1's obligations under the lease, for this unpaid amount.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The Kyoto District Court (first instance) sided with the tenant, X1. It found the renewal fee clause to be void under Article 10 of Japan's Consumer Contract Act. The court reasoned that the clause was ambiguously worded, the fee itself was akin to a gift with little reciprocal value for the tenant, and it imposed a heavier burden on the lessee than envisaged by the Civil Code's basic definition of a lease (use of property in exchange for rent). The court also highlighted the typical disparity in information and negotiating power between landlords and tenants and suggested X1 had entered the contract under a misunderstanding of the clause's nature.

- The Osaka High Court upheld this decision, also deeming the renewal fee clause invalid. The landlord, Y, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on July 15, 2011, overturned the lower courts' decisions regarding the renewal fee, ultimately finding the clause in this particular case to be valid.

Defining the Nature of Renewal Fees

The Court first addressed the legal character of renewal fees. It stated that the specific nature of a renewal fee in any given contract should be determined by comprehensively considering all circumstances surrounding the lease, including the parties' situations before and after the contract's formation and the process leading to the inclusion of the renewal fee clause.

However, the Court opined that, generally, renewal fees serve as part of the landlord's overall business income, alongside regular rent payments. In return for paying the renewal fee, the tenant can smoothly continue to use the leased property. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that renewal fees typically possess a "composite nature" (複合的な性質 - fukugōtekina seishitsu). This composite nature includes aspects of:

- A supplement to or prepayment of rent (賃料の補充ないし前払 - chinryō no hojū naishi maebarai).

- Consideration for the continuation of the lease agreement (賃貸借契約を継続するための対価 - chintaishaku keiyaku o keizoku suru tame no taika).

Analyzing Renewal Fee Clauses under Consumer Contract Act Article 10

Article 10 of the Consumer Contract Act voids consumer contract clauses that, in violation of the fundamental principle of good faith (as stipulated in Article 1, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code), unilaterally harm the consumer's interests. It applies if the clause restricts a consumer's rights or expands a consumer's duties compared to what would apply under non-mandatory legal provisions (default rules).

The Supreme Court applied a two-step analysis:

- Does the Clause Aggravate Consumer-Lessee's Duties?

The Court affirmed that a renewal fee clause does aggravate the duties of a consumer-lessee. A standard lease agreement, under Article 601 of the Civil Code, essentially involves the provision of property for use in exchange for rent. A renewal fee is an additional monetary obligation not inherently part of this basic definition. Thus, such a clause imposes a burden beyond the default legal framework. - Does the Clause Unilaterally Harm Consumer Interests Against Good Faith?

This was the critical part of the analysis. The Court determined that whether a clause meets this standard depends on a comprehensive assessment of various factors, including the purpose of the Consumer Contract Act, the nature of the clause, the circumstances of the contract's formation, and any disparities in information or negotiating power.

Regarding renewal fee clauses specifically, the Court reasoned:Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded that a renewal fee clause, clearly and specifically written into a lease agreement, is not considered to "unilaterally harm consumer interests against the principle of good faith" under Article 10 of the Consumer Contract Act, unless special circumstances exist, such as the renewal fee amount being excessively high (高額に過ぎる - kōgaku ni sugiru) in light of the rent amount, the length of the renewal period, and other relevant factors.- Economic Rationality: Given their composite nature (partly rent-like, partly consideration for continuation), renewal fees are not entirely devoid of economic rationality.

- Public Knowledge: It is a publicly known fact (公知 - kōchi) that the practice of paying renewal fees upon lease expiration exists in certain regions of Japan.

- Historical Treatment by Courts: Historically, in court-mediated settlements and other judicial proceedings, renewal fee clauses have not been automatically treated as void for being contrary to public order and morals.

- Information/Negotiation Disparity: If a renewal fee clause is clearly and specifically stated (一義的かつ具体的に記載 - ichigiteki katsu gutaiteki ni kisai) in the lease agreement, leading to a clear agreement on its payment, it cannot be assumed that an "unoverlookable disparity" (看過し得ないほどの格差 - kanka shi enai hodo no kakusa) in information or negotiating power exists between the landlord and tenant concerning this specific clause.

Application to the Case at Hand

In X1 and Y's lease:

- The renewal fee clause was found to be clearly and definitively stated in the written contract.

- The fee was set at two months' rent for each one-year renewal period.

The Supreme Court did not find this amount to be excessively high under the circumstances. Therefore, the clause was deemed valid and not void under Article 10 of the Consumer Contract Act. The Court also briefly stated that the clause did not violate Article 30 of the Land and Building Lease Act (which invalidates special contract terms disadvantageous to a building lessee if they contravene certain protective provisions of that Act).

Consequently, the Supreme Court ruled that X1's claim for a refund of previously paid renewal fees was without merit and that Y's counterclaim for the unpaid renewal fee (¥76,000 plus interest) was justified.

Understanding the Court's Stance: Commentary and Implications

This 2011 judgment was the Supreme Court's first definitive ruling on the general validity of renewal fee clauses and has significant implications.

Significance of the Ruling

Prior to this decision, while many lower courts and legal scholars considered renewal fee agreements generally valid if mutually agreed upon, the enactment of the Consumer Contract Act in 2001 led to a new wave of challenges, with some lower courts indeed finding such clauses void under Article 10. The Supreme Court's decision provided a binding precedent.

The "Composite Nature" of Renewal Fees

The Court's description of renewal fees having a "composite nature," including being "consideration for continuing the lease agreement," was a somewhat novel phrasing. Legal commentators have discussed how this aligns with traditional academic categorizations of renewal fees (e.g., as payment for the landlord waiving their right to refuse renewal, as consideration for strengthening the tenant's leasehold rights, or as a fee for re-establishing the lease). The exact scope of this "consideration for continuation" continues to be analyzed.

Critiques of the Consumer Contract Act Analysis

Some legal scholars have raised questions about certain aspects of the Supreme Court's reasoning for upholding the clause under Article 10:

- "Public Knowledge" of the Custom: The argument that a custom is "publicly known" might not fully address whether that custom is itself fair or reasonable, especially when the very legitimacy of the custom is under scrutiny. The existence of a practice doesn't automatically shield it from an unfairness review under the Consumer Contract Act.

- Historical Non-Invalidation: That courts previously didn't find renewal fees to be against general public policy doesn't necessarily dictate their validity under the more specific consumer protection lens of Article 10 of the Consumer Contract Act.

- "Clear and Specific Statement": While clarity on the amount and timing of the fee is essential for a valid agreement (i.e., for the formation of the clause), some commentators argue that this doesn't fully address potential underlying information or negotiation power imbalances regarding the justification or legal nature of the fee. Some lower courts had previously suggested that landlords might need to explain the purpose of the fee to overcome such imbalances. The Supreme Court's standard appears less demanding on this point.

Analogy to Judicial Review of "Central Clauses"

The Supreme Court's approach—upholding the clause as long as it's clearly disclosed and the amount isn't "excessively high"—is seen by some as analogous to the generally restrained approach courts take when reviewing "central clauses" (core terms like price) of a contract. This suggests that renewal fees might only be invalidated in relatively rare cases where the amount is demonstrably exorbitant.

Interaction with Statutory Renewal Protections

Japan's Land and Building Lease Act provides robust protections for tenants, including rights to statutory renewal of leases unless the landlord has "just cause" for refusal. These are mandatory provisions designed to ensure housing stability.

- A key criticism, not directly addressed by the Supreme Court in this judgment, is that renewal fee clauses might effectively allow landlords to charge tenants for a lease continuation that they might otherwise be entitled to by statute. Questions remain about whether tenants, often facing information and bargaining power disadvantages, truly make a free and informed decision to pay such fees versus asserting their statutory rights, especially when the precise legal justification for the fee can be opaque. Some even argue that if statutory renewal is a tenant's right, then the notion of a renewal fee being "consideration for the landlord waiving a right to refuse renewal" is inherently problematic.

Future Challenges and the Path to Transparency

Around the same time as this renewal fee decision, the Supreme Court also issued rulings upholding "shikibiki" clauses (special agreements for fixed, non-refundable deductions from security deposits at the end of a lease) using similar logic: valid if clearly stated and the amount is not excessively high.

Practices like renewal fees and shikibiki can potentially obscure the true total cost of renting by presenting a lower monthly rent while levying additional charges at other points in the lease cycle. Legal commentators suggest a continuing need for greater transparency in rental housing costs, perhaps through standardized "total estimated rent" displays, and potentially for more specific legislative rules addressing these types of special fees within the Land and Building Lease Act itself.

Conclusion

The 2011 Supreme Court decision on renewal fees established a crucial legal benchmark in Japan. It confirmed that such fees are not automatically invalid under consumer protection law but are subject to review for clarity of agreement and, critically, for whether the amount charged is "excessively high." While providing a degree of legal certainty, the ruling also leaves room for ongoing academic and societal discussion about the fundamental nature, fairness, and transparency of these common financial obligations in Japanese residential leases.