The Price of Progress: Valuing Restricted Land in Japanese Expropriation Law

Date of Judgment: October 18, 1973

Case: Land Expropriation Compensation Claim Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction: The Dilemma of Planning Restrictions and Fair Value

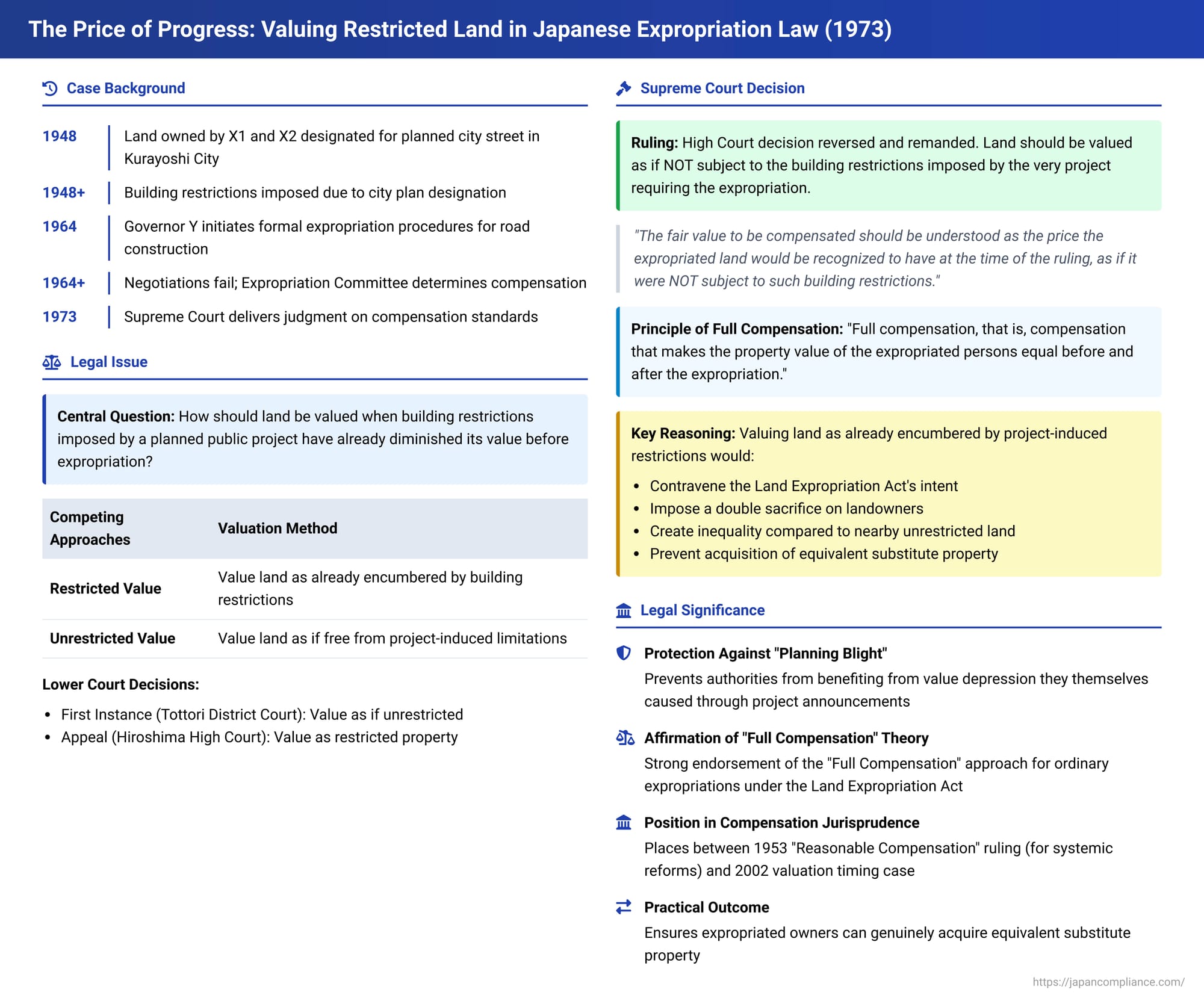

When private land is earmarked for a public project, such as a new road or city development, a complex situation often arises. Long before the land is formally expropriated, its use may be curtailed by building or other restrictions imposed due to the very public plan it is meant to serve. If these restrictions depress the land's market value, a critical question emerges upon expropriation: should the compensation paid to the owner reflect this diminished value, or should it be based on the land's value as if it were free from such project-induced limitations? A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on October 18, 1973, addressed this very issue, establishing a crucial principle for ensuring fair compensation to landowners.

The Case of X1 and X2: A City Road Plan and a Valuation Dispute

The case involved two individuals, X1 and X2, who owned parcels of land in Kurayoshi City. Back in 1948, their land was officially designated as part of a planned city street under Japan's old City Planning Act. As is common in such situations, this designation brought with it building restrictions, limiting how the owners could develop or alter their property.

Years later, in 1964, Y, the Governor of Tottori Prefecture, acting as the project undertaker, initiated formal expropriation procedures for X1 and X2's land to construct the planned road. Negotiations for a voluntary sale failed. The Governor then sought and received a ruling from the Minister of Construction confirming the expropriation. Subsequently, the Tottori Prefectural Expropriation Committee determined the amount of monetary compensation to be paid to X1 and X2.

Unhappy with the amount, X1 and X2 sued. They argued that the compensation offered by the Expropriation Committee was unfairly low, especially when compared to the prices of similar nearby land not affected by the road plan. The core of their dispute centered on how their land should be valued: as land already encumbered by building restrictions due to the road project, or as land free from such limitations.

The Lower Courts' Conflicting Views

The path through the lower courts revealed differing judicial philosophies on this issue:

- The first instance court (Tottori District Court, Kurayoshi Branch) sided partially with the landowners. It held that the compensation should be calculated by valuing the land as if it were unrestricted, essentially ignoring the depressing effect of the impending expropriation and the associated building limitations.

- However, the appellate court (Hiroshima High Court, Matsue Branch) reversed this. It ruled that the compensation should indeed be based on the land's value as restricted property. Since building restrictions were legally in place due to the city plan, the court found that this diminished value was the correct basis for compensation, leading to a dismissal of X1 and X2's claims.

Dissatisfied, X1 and X2 appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: The "Full Compensation" Principle

The Supreme Court, in its First Petty Bench judgment, overturned the appellate court's decision and remanded the case for reconsideration. The ruling provided a strong affirmation of the principle of "full compensation" in expropriation cases.

"Full Compensation" Defined:

The Court began by stating that loss compensation under Japan's Land Expropriation Act is intended to fully restore the "special sacrifice" borne by landowners whose property is taken for a specific public project. This requires:

"full compensation, that is, compensation that makes the property value of the expropriated persons equal before and after the expropriation."

When compensation is monetary, the Court clarified, it must be an amount sufficient for the expropriated landowners "to acquire equivalent substitute land or other property in the vicinity." The Court identified Article 72 of the then-applicable (pre-1967 amendment) Land Expropriation Act as the provision embodying this principle of full compensation.

Valuation of Land Subject to Planning Restrictions:

Crucially, the Supreme Court extended this principle to land burdened by building restrictions imposed as a consequence of a city planning project for which the land is ultimately expropriated. It held that:

"the fair value to be compensated... should be understood as the price the expropriated land would be recognized to have at the time of the [Expropriation Committee's] ruling, as if it were NOT subject to such building restrictions."

Reasoning for Disregarding Project-Induced Restrictions:

The Court acknowledged that there was no explicit legal provision to independently compensate landowners for the losses incurred merely from the imposition of such building restrictions before expropriation. However, it reasoned that this lack of separate compensation for the restrictions themselves does not mean that, upon actual expropriation, the land should be valued as if it were inherently less valuable due to those same restrictions.

To value the land as already encumbered by the project-induced restrictions would:

- Contravene Legislative Intent: It would go against the spirit and purpose of the Land Expropriation Act, which aims for fair and complete indemnification.

- Impose a Double Sacrifice: Landowners would suffer first from the limitations on their property rights (without separate compensation) and then again from a lowered expropriation value based on those very limitations.

- Create Inequality: It would lead to a grossly unfair outcome compared to owners of nearby land not subject to such restrictions, violating the principle of equality that underpins loss compensation.

- Prevent Restoration: It would make it practically impossible for the expropriated owners to obtain genuinely equivalent substitute property, thereby defeating the core objective of full compensation.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the appellate court had erred in its interpretation of Article 72 of the Land Expropriation Act by valuing the land as already diminished by the building restrictions.

Unpacking "Full Compensation" in the Context of Planning Blight

This 1973 Supreme Court decision is particularly significant for addressing what is often termed "planning blight." Planning blight occurs when the announcement or designation of land for a future public project causes its market value to decline, or stagnate, due to the uncertainty and restrictions imposed, long before any formal expropriation takes place. If the expropriating authority were then allowed to acquire the land at this blighted value, it would essentially be capitalizing on a depreciation it itself caused.

The Supreme Court's ruling effectively counters this by mandating that the valuation for expropriation purposes must disregard these project-specific restrictions. It ensures that the landowner is compensated based on the land's potential value in an open market, free from the shadow of the impending public project.

The Broader Jurisprudence: "Full Compensation" vs. "Reasonable Compensation"

The 1973 ruling and its strong endorsement of "full compensation" occupy an important place in the broader evolution of Japanese jurisprudence on "just compensation" under Article 29, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution.

- A key earlier case, the 1953 Grand Bench decision concerning post-war land reforms (the Owner Farmer Establishment case), had established the "Reasonable Compensation" theory. This theory held that "just compensation" means a rationally calculated, reasonable amount based on economic conditions at the time, which does not necessarily have to perfectly match full market value. This 1953 ruling was often seen as tailored to the unique, large-scale, systemic nature of the land reforms.

- The 1973 decision in the present case, with its explicit demand for "full compensation" to make the landowner's property value whole, was widely viewed by legal scholars as aligning with or championing the "Full Compensation" theory, at least for ordinary expropriations under the Land Expropriation Act. Many saw it as reflecting a constitutional ideal for such takings.

- Later, a 2002 Supreme Court decision (Heisei 14.6.11) dealt with the constitutionality of a Land Expropriation Act provision that fixed the valuation timing to the public notice of project approval (adjusted for general inflation). Interestingly, when discussing the constitutional meaning of "just compensation," the 2002 Court cited the 1953 "Reasonable Compensation" ruling, not the 1973 "Full Compensation" ruling. However, even in 2002, the Court affirmed that the Land Expropriation Act enables the expropriated person to receive "compensation that makes their property value equal before and after," language that echoes the sentiment of the 1973 decision.

This has led to scholarly discussion on how these precedents interrelate. One prevailing interpretation is that the "Reasonable Compensation" standard from 1953 might represent the constitutional minimum or floor for "just compensation." Specific statutes, like the Land Expropriation Act, can (and often do) aim for a higher standard, such as the "Full Compensation" articulated in the 1973 decision. This allows for consistency across these key rulings, recognizing that while the Constitution provides a baseline of reasonableness, legislative policy may strive for complete financial restoration for property owners affected by expropriation.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's October 18, 1973, decision is a vital judgment in Japanese expropriation law. It ensures that landowners are not unfairly penalized by receiving reduced compensation due to building restrictions imposed by the very public project for which their land is ultimately taken. By mandating valuation as if such project-induced restrictions did not exist, the Court strongly upheld the principle of "full compensation," aiming to truly restore the landowner's financial position to what it was before the expropriation.

This ruling prevents the state from benefiting from a "planning blight" of its own making and reinforces fairness and equality in the distribution of public burdens. It stands as a key protection for property owners facing expropriation, ensuring that the price of public progress does not fall disproportionately on those whose land is required for it.