The Price of a View: Japan's Supreme Court Recognizes "Landscape Interest" in Kunitachi City Case

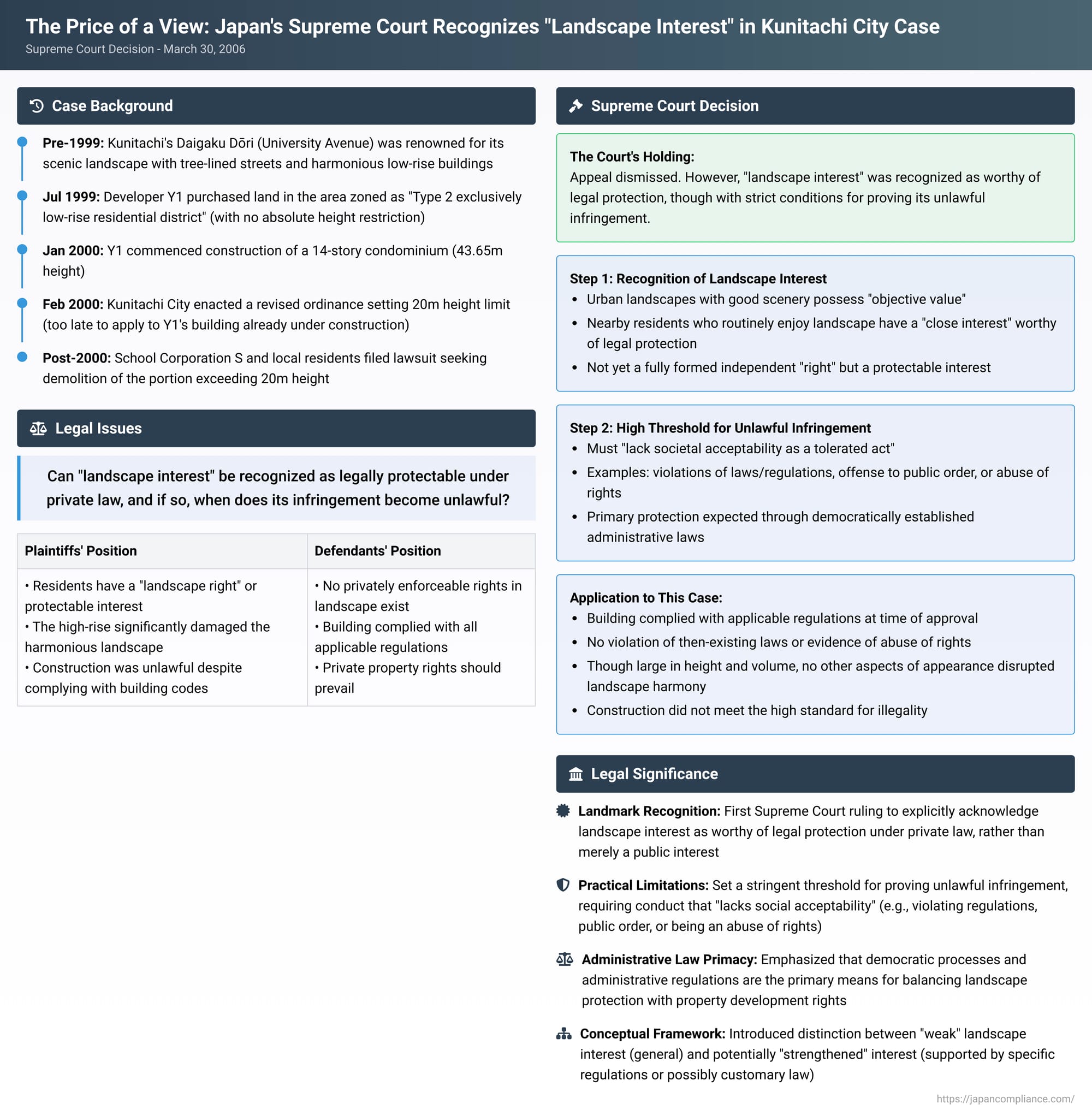

The aesthetic quality of our surroundings, often referred to as "landscape," is something many cherish. But can a pleasant view be legally protected? And if so, when does its disruption by new development become an unlawful act, especially if the development complies with all existing building codes? These questions were at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 30, 2006 (Heisei 18), concerning a controversial high-rise construction in Kunitachi City, Tokyo, an area renowned for its scenic University Avenue (Daigaku Dōri). This case, formally the Building Demolition, etc. Claim Case (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, Heisei 17 (Ju) No. 364), marked a significant step in Japanese law by acknowledging "landscape interest" (keikan rieki) as a legally protectable interest, albeit with stringent conditions for proving its unlawful infringement.

The Kunitachi Landscape and the Controversial Development

Kunitachi City's Daigaku Dōri is a well-known thoroughfare, celebrated for its harmonious landscape featuring broad sidewalks, lines of cherry and ginkgo trees, and buildings that generally maintain a continuous and modest height, creating an environment of academic serenity largely influenced by University H. Most of this area was zoned as a "Type 1 exclusively low-rise residential district," where building height was restricted to 10 meters.

However, the specific parcel of land at the center of the dispute (referred to as "the Land") was, due to historical zoning decisions, an exception. It was designated as a "Type 2 exclusively low-rise residential district" which, at the time, had no absolute height restriction.

In July 1999, Developer Y1, a company specializing in housing development, purchased the Land. In January 2000, Y1 commenced construction of a 14-story condominium building with a maximum height of 43.65 meters. This starkly contrasted with the prevailing low-rise character of Daigaku Dōri.

A coalition of plaintiffs, X (including School Corporation S which operated schools in the vicinity, along with students, faculty, and local residents, some organized into associations like D and E), vehemently opposed the construction. They filed a lawsuit seeking an injunction to halt the construction and, after the building's completion, demanded the demolition of the portion exceeding 20 meters in height.

The case took a notable turn when the court of first instance sided with plaintiffs X, ordering partial demolition based on tort law, finding an unlawful infringement of their interests. This decision garnered significant public attention. However, the High Court (the "original instance court" in the Supreme Court's judgment text) overturned this ruling. It denied the existence of privately enforceable rights or interests in landscape under private law and dismissed the plaintiffs' claims. Critically, both lower courts found that the construction of the building by Y1 (with design and execution by Construction Company Y2) complied with the Building Standards Act and other relevant administrative regulations in force at the time of its approval. Plaintiffs X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Acknowledgment (March 30, 2006)

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed the appeal by plaintiffs X. However, the significance of the judgment lies not in this dismissal, but in its detailed reasoning, which, for the first time at this level, explicitly recognized "landscape interest" as an interest worthy of legal protection in principle, even under private law.

The Court focused its analysis on whether the construction constituted a tortious act due to the infringement of landscape interests.

The Two-Step Reasoning: Recognizing the Interest, Defining Infringement

The Supreme Court's judgment can be understood through a two-step analytical process:

Step 1: Landscape Interest is Legally Protectable

The Court first established the legitimacy of landscape interest:

- Objective Value of Urban Landscape: The Court stated that an urban landscape, when it constitutes good scenery, shapes people's historical or cultural environment, and forms a rich living environment, possesses objective value.

- Protectable Interest of Residents: Consequently, individuals residing in close proximity to a good landscape, who routinely enjoy its benefits, have a "close interest" in relation to the infringement of this objective value. The benefit these individuals derive from enjoying a good landscape (their "landscape interest") is "worthy of legal protection" (hōritsujō hogo ni ataisuru).

- The Court noted the increasing societal and legislative recognition of landscape value, referencing the Kunitachi City's own Landscape Ordinance (enacted 1998), similar ordinances in other municipalities, Tokyo's Metropolitan Landscape Ordinance (1997), and the national Landscape Act (enacted June 2004, effective December 2004). The Landscape Act, for example, declares good landscape an "irreplaceable common asset for the nation".

- Interest, Not a "Right": However, the Court clarified that while this "landscape interest" is protectable, it does not, at the current time, possess such clear substance as to be termed a "landscape right" (keikanken) in the sense of a fully formed, independent private right.

Step 2: The High Bar for Unlawful Infringement

Having recognized landscape interest, the Court then addressed when its infringement becomes unlawful in the context of a tort claim (Article 709 of the Civil Code). It set a high threshold:

- Comprehensive Consideration: Whether a building's construction constitutes an illegal infringement of a third party's landscape interest must be judged by "comprehensively considering" various factors. These include the nature and content of the infringed landscape interest, the environmental context of the landscape's location, and the mode, degree, and history of the infringing act.

- Key Limitations and Considerations in Assessing Illegality: The Court highlighted several factors that temper the direct enforceability of landscape interests through tort law:

- Nature of Harm: Infringement of landscape interest, unlike some other nuisances, does not inherently cause direct "lifestyle disturbance or health damage" to the aggrieved parties.

- Balancing with Property Rights: Protecting landscape interests inevitably involves imposing restrictions on the property rights of landowners and developers. This can lead to conflicts of opinion among residents and between residents and property owners regarding the scope and content of such protections.

- Primacy of Democratic Processes: Because of these complexities, the protection of landscape interests and the accompanying regulation of property rights are "primarily expected to be carried out through administrative laws and ordinances of the relevant region, which are established through democratic procedures".

- The Standard for Illegality: Given these considerations, for an act to be deemed an illegal infringement of landscape interest, it must, "at the very least, lack societal acceptability as a tolerated act in terms of its mode and degree" (shakaiteki ni yōnin sareta kōi toshite no sōtōsei o kaku). The Court provided examples of conduct that would meet this high standard:

- The infringing act violates criminal statutes or administrative regulations.

- The infringing act offends public order and morals (kōjo ryōzoku ihan).

- The infringing act constitutes an abuse of rights (kenri no ran'yō).

Application to the Kunitachi Case

Applying this framework to the facts of the Kunitachi case, the Supreme Court concluded:

- Existence of Landscape Interest: Plaintiffs X, residing near and daily enjoying the benefits of the Daigaku Dōri landscape—with its historical background as an area developed as an academic town and its recognized scenic qualities—did indeed possess a landscape interest worthy of protection.

- No Unlawful Infringement: However, the construction of Y1's building did not meet the high threshold for illegal infringement:

- Compliance with Administrative Law: The building received its architectural confirmation on January 5, 2000, and construction began thereafter. At that point, Kunitachi City had not implemented specific ordinances that would regulate this particular construction to protect the landscape in a way that was violated.

- Although Kunitachi City later (February 1, 2000, after construction had begun) promulgated a revised ordinance setting a 20-meter height limit for the area under a new district plan, this regulation could not retroactively apply to Y1's building, which was already "actually under construction" (a legally defined status protecting ongoing projects from new regulations). The building also complied with other administrative regulations like those concerning sun-shadow restrictions.

- Nature of the Building and Conduct: The Court acknowledged that the building was of "considerable volume and height" (14 stories, 43.65m, 353 units). However, "apart from that point, it was difficult to recognize any aspect in the external appearance of the building that disrupted the harmony of the surrounding landscape".

- The Court found no other circumstances suggesting that the construction violated then-existing criminal or administrative laws, was contrary to public order and morals, or constituted an abuse of rights by Y1.

- Therefore, the Court concluded that the building's construction did not lack "societal acceptability as a tolerated act" and thus did not illegally infringe upon the landscape interests of plaintiffs X. The subsequent unit owners (U) who purchased units from Y1 were also party to the appeal.

Interpreting the Judgment: A Breakthrough with Significant Caveats

The Kunitachi landscape judgment has been widely discussed and analyzed by legal scholars in Japan.

Praise: Acknowledging Landscape as a Private Interest

The decision is broadly praised for being the first Supreme Court ruling to clearly affirm that "landscape interest" can be a private interest worthy of legal protection under tort law. Previously, many court decisions had treated landscape primarily as a public interest, making it difficult for individuals to seek remedies for its degradation through private law. This theoretical advancement was seen as a major step.

Criticism and Debate: The "Strict Illegality Standard"

Despite this recognition, many commentators have expressed concerns that the criteria for proving unlawful infringement are excessively strict, thereby limiting the practical significance of the newly acknowledged interest.

- The "Correlation Theory" Influence: The Court's high threshold for illegality (requiring conduct that is "socially unacceptable," akin to violating laws or being an abuse of rights) is seen by some as reflecting the "correlation theory" (sōkan kankei setsu) in Japanese tort law. This theory suggests that if a legally protected interest is considered "weaker" or less central (as the Court arguably positions landscape interest by noting it doesn't typically cause health damage ), then only a particularly egregious or independently wrongful act of infringement will be deemed illegal. The Court's finding that, apart from its height and volume, the building's appearance wasn't disharmonious, seems to align with this; height and volume are key to landscape impact, but if the act of building itself (the "mode of conduct") isn't otherwise wrongful (e.g., violating a specific regulation), the impact alone might not suffice. Some scholars have questioned whether an abuse of rights argument could have been more thoroughly explored given the context.

The "Primacy of Administrative Law" Interpretation

A key aspect of the judgment is its emphasis on administrative laws and local ordinances as the primary means for landscape protection. This is not merely to say that violating such laws is one way to prove "egregious conduct." A deeper interpretation, favored by some scholars, suggests that these democratic, regulatory mechanisms are seen by the Court as the principal tools for defining the scope and allocating the protection of landscape interests in the first place.

- "Weak" vs. "Strengthened" Landscape Interests: This perspective can lead to a conceptual distinction:

- "Weak Landscape Interest": This refers to the general interest in enjoying good scenery that possesses objective value (as per point 1 of the judgment summary). Protection for this baseline interest via tort law would require meeting the high "socially unacceptable conduct" threshold outlined in point 4c of the judgment summary (e.g., violation of unrelated administrative laws, public order, abuse of rights). General landscape laws or broadly worded municipal landscape ordinances might only confer this level of "weak" interest unless they contain specific, concrete regulatory content.

- "Strengthened Landscape Interest": If specific administrative regulations—those that impose concrete behavioral controls on development for the express purpose of protecting a particular landscape—are in place, the landscape interest in that area could be considered "strengthened". In such cases, a violation of those specific landscape-protection regulations might more directly lead to a finding of unlawful infringement in a tort claim. The logic is that the democratic legislative process has already balanced property rights against landscape protection by enacting these specific rules. Infringement of such a specifically protected interest might be treated similarly to the infringement of an absolute right, where illegality is more readily presumed from the violation itself.

- In the Kunitachi case, the city's Landscape Ordinance and the earlier designation of the Daigaku Dōri area as a candidate for a "landscape formation priority district" could have hinted at an intention to provide enhanced protection. However, these did not, at the time of the building's approval, translate into the kind of concrete, binding height restrictions that were later introduced. The appellate court, whose factual findings the Supreme Court generally relies upon, did not establish facts that would have allowed the Supreme Court to rule on a "somewhat strengthened" interest based on these pre-existing but less specific measures.

Beyond Codified Law: The Potential for "Customary Law Landscape Interest"

The Supreme Court's judgment did not address the scenario where specific administrative regulations protecting a landscape are absent, but local residents have, through their own long-standing, collective efforts and voluntary agreements (such as self-imposed building restrictions or collaborative maintenance), actively co-created and preserved a unique and cherished landscape.

- Many legal scholars argue that such "jointly formed landscapes" (kyōdō keisei no keikan) could give rise to a protectable, possibly "strengthened," landscape interest, potentially grounded in customary law. The sustained collective efforts and sacrifices of the community would provide the basis for the "legal conviction" (hōteki kakushin)—the belief that such a norm is legally binding—which is a necessary element for the recognition of customary law.

- The Supreme Court's silence on this possibility is not interpreted as a denial. Since the lower courts had not made findings of fact regarding such "joint formation" in the Kunitachi case, the issue was not directly before the Supreme Court. Thus, the judgment does not preclude the future recognition of landscape interests arising from such community-led initiatives. This reading suggests that criticisms of the judgment as overly reliant on "administrative law primary-ism" may not fully account for this unaddressed avenue.

- If such a customary law-based landscape interest were recognized, it would likely benefit all who "routinely enjoy its benefits" in the area, not just those who actively participated in its creation, aligning with the idea of landscape interest as a form of personal right (jinkakuteki hōeki) accessible to all similarly situated individuals.

Concluding Thoughts

The Kunitachi Daigaku Dōri case was a watershed moment in Japanese jurisprudence, marking the Supreme Court's first explicit acknowledgment that aesthetic landscape interests can be worthy of legal protection under private law. This was a conceptual victory for proponents of landscape preservation.

However, the practical application of this principle remains challenging. The Court placed primary responsibility on democratic and administrative processes—namely, legislation and local ordinances—for defining the specific contours of landscape protection and for balancing these interests against development rights. For individuals seeking to protect landscape interests through private tort law, the path is difficult unless the infringing conduct is independently unlawful (e.g., violates existing administrative regulations, building codes, or constitutes an abuse of rights) or unless, potentially, a "strengthened" landscape interest derived from highly specific protective regulations or established customary law can be demonstrated.

The Kunitachi judgment has undeniably spurred further legal and societal discussion on landscape governance, the crucial role of local governments in enacting effective landscape ordinances, the importance of citizen participation in landscape planning and formation, and the ongoing quest to find an appropriate balance between urban development and the preservation of cherished environments.