The Price of a Lie: A Japanese Ruling on Fraud and "Equivalent Value"

Imagine you are tricked by a salesperson's elaborate lies into buying a product. You later discover the product's purported special qualities are entirely fabricated. However, you also learn that you paid the standard market price for the item—no more, no less. In a simple accounting sense, you haven't "lost" any money. But have you been the victim of a crime? Can a transaction be fraudulent if the victim receives an item of "equivalent value"?

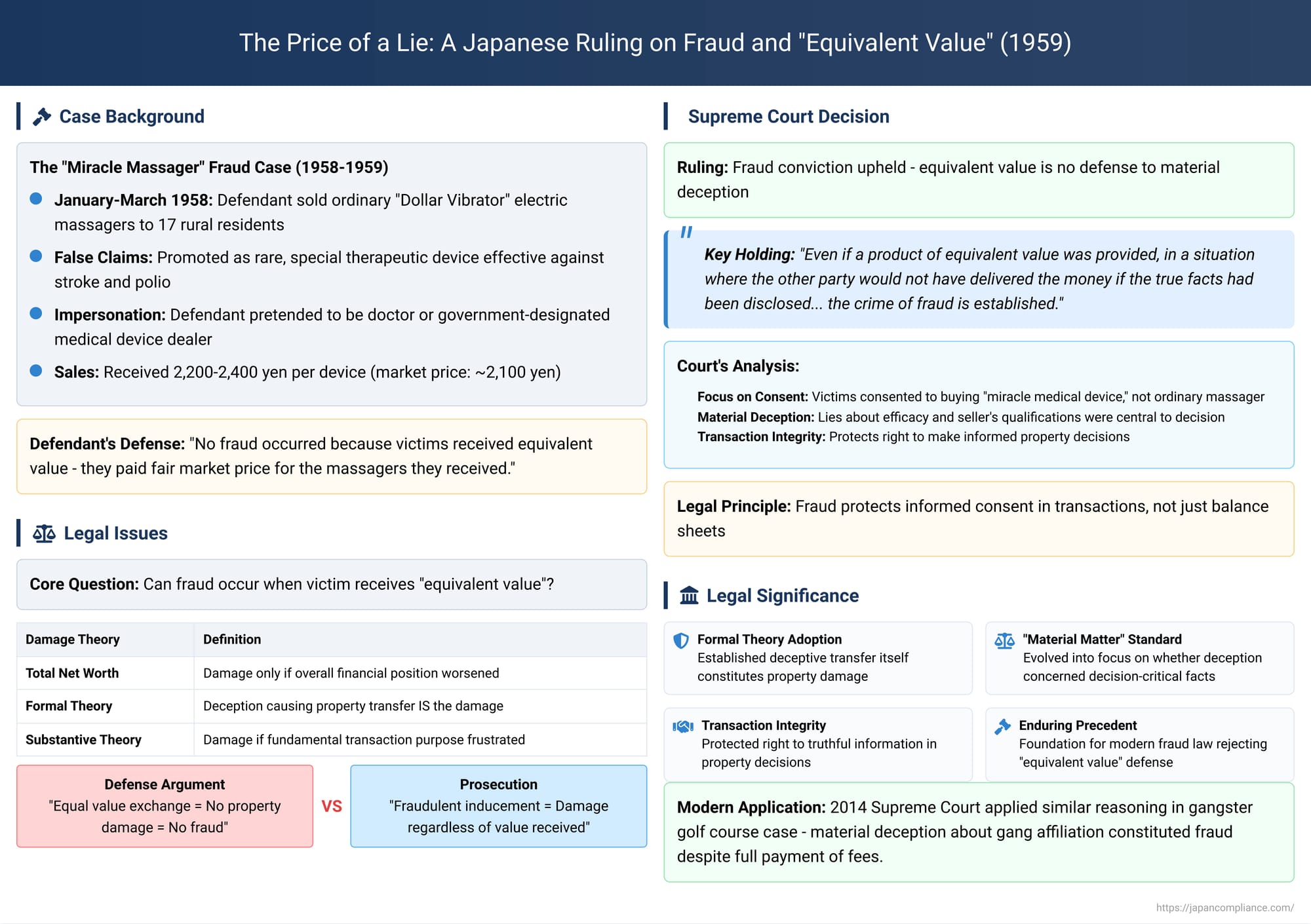

This fundamental question was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on September 28, 1959. The case, involving a defendant who sold ordinary electric massagers as miracle medical cures, established a crucial principle in Japanese fraud law: the crime of fraud protects not just a person's balance sheet, but their right to make informed decisions about their property. The Court ruled that deceiving someone into a transaction they would otherwise have rejected is a crime, even if they pay a "fair" price.

The Facts: The "Miracle" Massager

The defendant in the case was neither a doctor nor a licensed seller of medical equipment. He targeted rural residents, selling a common, commercially available electric massager known as a "Dollar Vibrator".

His sales pitch, however, was built on a series of deceptions. He falsely claimed that the device was a new, special, and difficult-to-obtain therapeutic instrument with extraordinary effectiveness against serious illnesses like stroke and polio. To bolster his credibility, he also pretended to be a doctor or a government-designated medical device dealer.

Between January and March of 1958, he successfully used these false pretenses to sell the massagers to 17 people, receiving payments ranging from 2,200 to 2,400 yen for each device.

The defendant was charged with and convicted of fraud. On appeal, his central defense was that he had not committed a property crime because the victims had suffered no financial loss. He argued that the fair retail price for the model of massager he sold was 2,100 yen, and that he had sold it for roughly that amount. Since the victims received an item of equivalent value to the money they paid, he contended, there was no damage and therefore no fraud.

The Legal Question: Is "No Financial Loss" a Defense to Fraud?

The defendant's argument goes to the heart of the definition of fraud. The crime of fraud (Article 246 of the Penal Code) is a property crime, and as such, Japanese law generally requires that the victim suffer some form of "property damage" (zaisan-jō no songai). The core question is, what constitutes "damage"? The debate has traditionally revolved around several competing legal theories.

- The "Total Net Worth" Theory: This theory takes a holistic view, arguing that damage only occurs if the victim's overall financial position is worse off after the transaction. It requires a comparison of the economic value of what was given versus what was received. This theory would seem to support the defendant's argument.

- The "Individual Property" Theory: This theory views fraud as a crime against a specific piece of property (in this case, the victims' cash). It has two main variants:

- Formal Theory: This influential view holds that the very act of being deceived into transferring property is the damage. The law protects the right to dispose of one's property freely and without being tricked. Under this view, the value of what is received in return is irrelevant.

- Substantive Theory: This view seeks a more "substantive" harm. It asks whether the victim failed to receive what they thought they were bargaining for. If the fundamental purpose of the transaction is frustrated by the deception, then there is substantive damage.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: The Lie Itself is the Harm

The Supreme Court decisively rejected the defendant's appeal and upheld his fraud conviction. In a concise but powerful statement, the Court laid down the principle that has guided Japanese fraud law ever since:

"Even if a product of equivalent value was provided, in a situation where the other party would not have delivered the money if the true facts had been disclosed, if the perpetrator intentionally discloses exaggerated facts contrary to the truth concerning the product's efficacy, etc., causes the other party to be mistaken, and receives the delivery of money, the crime of fraud is established."

The Court's logic was clear: the crime of fraud is not about the final balance sheet but about the fraudulent inducement. The victims in this case were not simply buying an electric massager. They were deceived into believing they were purchasing a rare and powerful medical device, a belief created entirely by the defendant's lies about its efficacy and his own qualifications. The transaction they consented to was not the one they actually received. Since they would never have paid the money had they known the truth, the defendant's act of taking their money through deception constituted fraud.

Analysis: A Doctrine in Evolution

The 1959 ruling is a classic example of the "formal" approach to property damage, where the unwanted transfer itself constitutes the harm. This remains a dominant trend in Japanese case law. For instance, courts have found fraud even where a victim was deceived into buying an object that was actually more valuable than the price paid, because the deception still induced a transaction they would not have otherwise made.

However, the law is not entirely rigid. The commentary on this case notes a counter-trend in certain situations where courts have denied fraud, suggesting a more "substantive" analysis. For example, in a case where an unlicensed individual pretending to be a doctor correctly diagnosed a patient and sold them the appropriate medicine at the correct price, the court found no fraud. The reasoning was that despite the deception about qualifications, the victim received the substance of what they were seeking—the right cure for their ailment—and thus suffered no substantive harm.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has moved towards a standard that harmonizes these approaches, focusing on whether the deception concerned a "material matter" (jūyō jikō) in the victim's decision-making process. This was famously illustrated in a 2014 case where a gangster, by hiding his affiliation, gained access to a golf course that explicitly banned gang members. Even though he paid the full fee, the Court found him guilty of fraud, reasoning that his status as a gangster was a "material matter" to the golf course's decision to grant him entry.

The 1959 "miracle massager" case fits perfectly within this modern "materiality" framework. The defendant's lies about the product's special medical properties and his own status as a doctor were undoubtedly "material matters" that were central to his victims' decision to purchase the device. The transaction was predicated on these material falsehoods.

Conclusion: The Enduring Importance of Informed Consent

The 1959 Supreme Court decision is a foundational ruling that establishes a vital principle in the law of fraud. It affirms that the crime protects not just the narrow accounting value of a person's assets, but their fundamental right to dispose of their property based on truthful information.

The enduring legacy of the case is its clear rejection of the "no harm, no foul" defense in the context of material deception. Providing a product of "equivalent value" is no excuse if that value was misrepresented and the entire transaction was induced by lies about matters crucial to the victim's consent. The decision underscores that the integrity of the transaction itself is a key component of the property rights protected by the criminal law.