The Power of Pronounced Intent: A 1966 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on "Benefit of Suit" in Complex Real Estate Title Disputes

Date of Supreme Court Decision: March 18, 1966

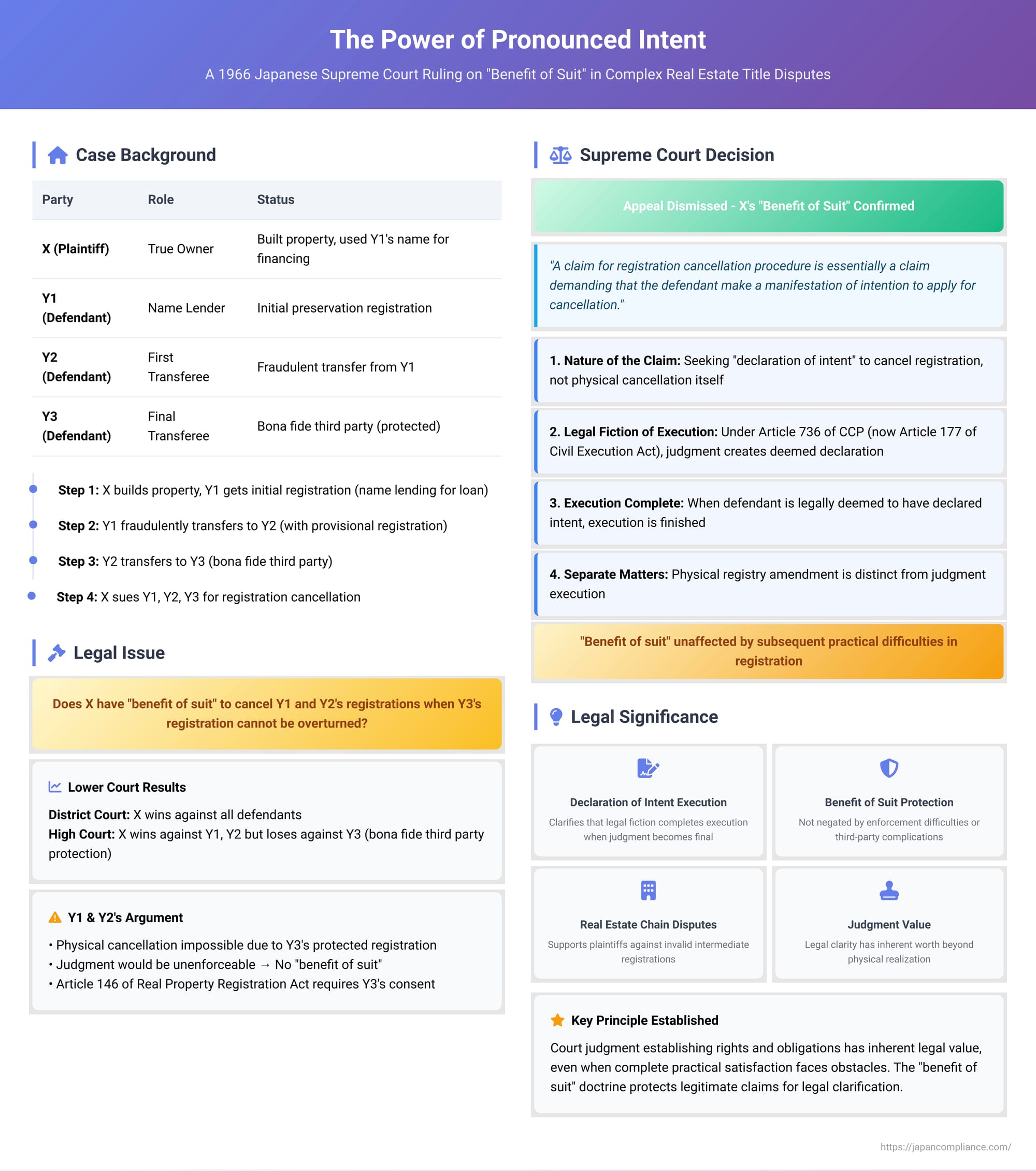

In the intricate world of real estate law, a clear title is paramount. However, chains of transactions, some potentially invalid, can cloud ownership, leading to complex litigation. A pivotal decision by the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan, rendered on March 18, 1966, addressed a nuanced question: Does a plaintiff have a legitimate "benefit of suit" (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki) when seeking the cancellation of intermediate, invalid property registrations if the final, current registration is held by a bona fide third party whose title cannot be overturned, thereby making the physical erasure of the earlier registrations from the official record practically challenging or even impossible in the usual sequence? This landmark case delved into the nature of claims for registration cancellation and the very meaning of "execution" of a judgment that orders a declaration of intent.

The Factual Tapestry: A Property's Troubled Registration History

The dispute centered around a building constructed by the plaintiff, X. The pertinent facts are as follows:

- Initial Registration: X, having built the property, required a loan from the Housing Loan Corporation. For reasons related to obtaining this financing, X, with the consent of Y1, had the initial ownership preservation registration (所有権保存登記 - shoyuuken hozon touki) for the building made in Y1's name. Legally, X remained the true owner.

- Fraudulent Transfers: Y1, apparently taking advantage of the property being registered in their name, then engaged in a series of maneuvers with Y2 and Y3.

- First, Y1, in collusion with Y2, effected an ownership transfer registration (所有権移転登記 - shoyuuken iten touki) to Y2. Simultaneously, a provisional registration securing a claim for future ownership transfer (所有権移転請求権保全仮登記 - shoyuuken iten seikyuuken hozen karitouki) was also made in Y2's favor, predicated on a purported sales agreement.

- Subsequently, Y2 transferred the property to Y3, and an ownership transfer registration was completed in Y3's name.

- X's Lawsuit: X, asserting their true ownership and the invalidity of all these subsequent registrations (Y1's initial preservation registration being a matter of name-lending, and the transfers to Y2 and Y3 being without legitimate basis), filed a lawsuit against Y1, Y2, and Y3. X sought court orders compelling each defendant to undertake the necessary procedures for the cancellation (抹消登記手続 - masshou touki tetsuzuki) of their respective registrations.

The Lower Courts' Decisions: A Partial Victory for X

The journey through the lower courts yielded mixed results for X:

- Court of First Instance (Morioka District Court, Hanamaki Branch): This court ruled entirely in X's favor, finding all the disputed registrations invalid and ordering Y1, Y2, and Y3 to proceed with their cancellation.

- High Court (Sendai High Court): On appeal, the High Court modified the first instance judgment:

- It upheld X's claims against Y1 and Y2, agreeing that their registrations were invalid and should be cancelled.

- However, it dismissed X's claim against Y3. The High Court applied Article 94, Paragraph 2 of the Japanese Civil Code by analogy. This provision protects a bona fide (good faith) third party who relies on a fictitious manifestation of intention between two other parties. The court found Y3 to be such a bona fide third party. Essentially, even if the initial arrangement between X and Y1 (leading to Y1's registration) was seen as a form of fictitious display of which X was aware or complicit, X could not assert the invalidity of that underlying situation against Y3, who had acquired the property in good faith from Y2.

This partial defeat for X at the High Court set the stage for the Supreme Court appeal. Because Y3's registration as the current owner was upheld, the practical question arose: If Y3's title is secure, what is the point of ordering Y1 and Y2 to cancel their (now intermediate and superseded) registrations?

The Appeal to the Supreme Court: A Challenge to the "Benefit of Suit"

Y1 and Y2 appealed to the Supreme Court. Their core argument was that X no longer had a "benefit of suit" in pursuing the cancellation of their registrations. They contended:

- Under Japanese real estate registration law (specifically, then-Article 146, Paragraph 1 of the Real Property Registration Act, now Article 68), if a third party (like Y3) has an interest that would be affected by a registration cancellation, that third party's consent (or a court judgment substituting for it) is typically required to proceed with the cancellation of earlier registrations in the chain.

- Since the High Court had dismissed X's claim against Y3, meaning Y3's registration would remain, the actual physical cancellation of Y1's and Y2's registrations in the official property register would be impossible to execute in a way that directly restored unencumbered title to X. Any attempt to erase Y1's and Y2's entries would be stymied by Y3's valid, subsequent registration.

- Therefore, they argued, a judgment ordering them to undertake cancellation procedures would be futile, serving no practical purpose for X. Such a lawsuit, lacking an achievable objective, should be dismissed for want of a "benefit of suit."

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 18, 1966, unequivocally rejected the arguments of Y1 and Y2 and dismissed their appeal. The Court's reasoning was a masterclass in distinguishing the legal effect of a judgment from the subsequent administrative steps of its implementation:

- Nature of a Claim for Registration Cancellation Procedure: The Court first defined what X was actually seeking. A claim for a "registration cancellation procedure" is, in essence, a claim demanding that the defendant make a "manifestation of intention" (意思表示 - ishi hyouji)—specifically, the intention to apply to the registry office for the cancellation of the specified registration.

- Execution of a Judgment Ordering Manifestation of Intent: The Court then pointed to the legal effect of a judgment ordering such a manifestation of intent. Under the then-Code of Civil Procedure Article 736 (the substance of which is now found in Article 177 of the Civil Execution Act), once a judgment compelling a party to make a declaration of intent becomes final and binding, that party is deemed to have made that declaration. The law itself supplies the intention.

- Completion of the Judgment's Execution: At the moment this legal fiction kicks in—the moment the defendant is deemed to have declared the required intention—the execution of that specific judgment is considered complete. The court's order compelling the declaration has achieved its immediate legal purpose.

- Distinction from Physical Registration Acts: The subsequent process of actually applying to the registry office and having the registration physically cancelled is a separate matter. The Supreme Court clarified that "it is not necessary to consider the carrying out of the cancellation registration as the execution of the said judgment."

- "Benefit of Suit" Unaffected by Subsequent Registrability: Consequently, the Court concluded that the "benefit of suit" for a claim seeking a registration cancellation procedure is not dependent on whether the actual cancellation in the registry is ultimately feasible. The legal interest in obtaining a judgment that defines a party's obligation to declare an intention stands on its own.

Applying this to the case, the Supreme Court held that since Y1 and Y2 were indeed obligated to X to undertake the procedures for cancelling their respective (invalid vis-à-vis X) registrations, X's claims against them were well-founded and should be upheld. The fact that Y3's registration further down the chain was indefeasible, and that this might (under then-Real Property Registration Act Article 146, Paragraph 1) render the physical erasure of Y1's and Y2's registrations impossible, did not strip X's lawsuit against Y1 and Y2 of its legal standing or "benefit of suit."

Deeper Implications and Legal Principles Illuminated

This 1966 Supreme Court decision carries profound implications for understanding several key legal concepts in Japanese civil procedure and property law:

1. Execution of an Obligation to Declare Intent (意思表示義務の執行 - ishi hyouji gimu no shikkou):

The core of the ruling rests on the unique mechanism for enforcing obligations that consist merely of declaring an intent. Japanese law, through Article 177 of the Civil Execution Act (and its predecessor), provides that a judgment ordering such a declaration, once final, results in the declaration being legally deemed to have been made. This "deemed declaration" or "fictitious declaration of intent" (意思表示の擬制 - ishi hyouji no gisei) means that the legal consequences that would flow from an actual declaration are achieved without needing to physically compel the debtor to speak or sign. The judgment itself, in effect, becomes the declaration. This is crucial because it means the "execution" of the court's order to declare intent is accomplished when the judgment is finalized, not when (or if) the registry is later amended.

2. The Japanese Real Estate Registration System:

Understanding this case requires a brief look at how Japanese real estate registration generally works:

- Joint Application Principle (共同申請主義 - kyoudou shinsei shugi): As a rule, most registrations affecting property rights (like transfers or cancellations) must be applied for jointly by the person who stands to gain from the registration (the "registration right holder" or 登記権利者 - touki kenrisha) and the person who stands to lose a registered right (the "registration obligor" or 登記義務者 - touki gimusha).

- Judgment in Lieu of Cooperation: If the registration obligor refuses to cooperate in the joint application, the registration right holder can sue them, seeking a judgment ordering them to perform the registration procedure (i.e., to declare their intent to apply). If successful, this judgment enables the right holder to apply for the registration unilaterally (this is known as "registration by judgment" or 判決による登記 - hanketsu ni yoru touki, as per Article 63 of the Real Property Registration Act).

- Cancellation of Chained Registrations: When seeking to cancel a series of registrations (e.g., A -> B -> C, and A wants to cancel the B and C registrations to restore A's title), the process usually involves cancelling them in reverse order of their creation, or in a manner that respects the interests of any bona fide parties in the chain. The issue in this case was that C's (Y3's) registration was upheld, disrupting the typical "domino effect" of cancellations.

3. The "Benefit of Suit" Doctrine (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki):

This doctrine is a fundamental prerequisite for maintaining a lawsuit in Japan. It essentially means the plaintiff must have a legitimate, recognized interest in seeking a judicial resolution.

- For Performance Claims (給付の訴え - kyuufu no uttae): Generally, if a plaintiff has a substantive right to demand a certain performance from the defendant, and that performance has not been rendered, the benefit of suit is acknowledged.

- When Execution is Problematic: The doctrine becomes more complex when the compulsory execution of a potential judgment appears impossible or exceptionally difficult. Historically, there was some debate, with certain older theories and court cases suggesting that if a judgment would clearly be unenforceable, there might be no benefit in suing for it (perhaps only a declaratory judgment action would be permissible).

- Prevailing Modern View: The current mainstream view, strongly reinforced by this 1966 Supreme Court decision, is that the "benefit of suit" for a performance claim is not automatically negated merely because the subsequent physical enforcement or realization of the judgment's objective faces obstacles. A judgment has inherent value in officially declaring the rights and obligations of the parties. It establishes legal clarity, can serve as a basis for future claims (e.g., for damages), or might become fully realizable if circumstances change (e.g., if Y3 later consented or their legal status changed).

4. Rationale for Upholding "Benefit of Suit" in This Specific Case:

The Supreme Court found that X had a valid interest in obtaining judgments against Y1 and Y2 for several underlying reasons, even if Y3's title complicated the final picture:

- The judgments against Y1 and Y2 would officially confirm the invalidity of their respective registrations vis-à-vis X. This is a significant legal clarification.

- While the Court did not explicitly base its reasoning on the speculative possibility of Y3 later consenting to a full cancellation (which some academic commentators have discussed as a potential justification for the benefit of suit), such a judgment against Y1 and Y2 would be indispensable if Y3 did ever agree to a broader settlement to clear the title. Without these judgments, X might have to re-litigate against Y1 and Y2.

- The core reasoning, however, seems to be more fundamental: X had a right to demand the specific performance (the declaration of intent to cancel) from Y1 and Y2 because, as between X and Y1/Y2, the registrations were invalid. The enforceability of this specific type of "declaration of intent" judgment is achieved by legal fiction upon finalization, irrespective of downstream practicalities in the registry.

Lasting Significance

The 1966 Supreme Court decision in this registration cancellation case remains a cornerstone of Japanese civil procedure. It robustly affirms that the legal "execution" of a judgment ordering a declaration of intent is complete when that intent is deemed by law to have been made. The subsequent practicalities of realizing the ultimate goal (like amending a property register) are distinct and do not retroactively nullify the plaintiff's initial interest in obtaining the judgment for the declaration itself.

This ruling provides vital support for plaintiffs who seek to vindicate their rights against parties who have participated in creating invalid links in a chain of title, even when a subsequent bona fide purchaser further down the line complicates the complete restoration of the original owner's registered status. It underscores the principle that a court judgment has inherent value in establishing legal rights and duties, and the "benefit of suit" will not be lightly denied, even if the path to full practical satisfaction is not immediately clear or unobstructed. The decision champions legal clarity and the enforceability of obligations to declare intent, a crucial mechanism in a legal system that often relies on cooperative, declared intentions for administrative processes like property registration.