The Possession of the Deceased: A Japanese Ruling on Theft from a Murder Victim

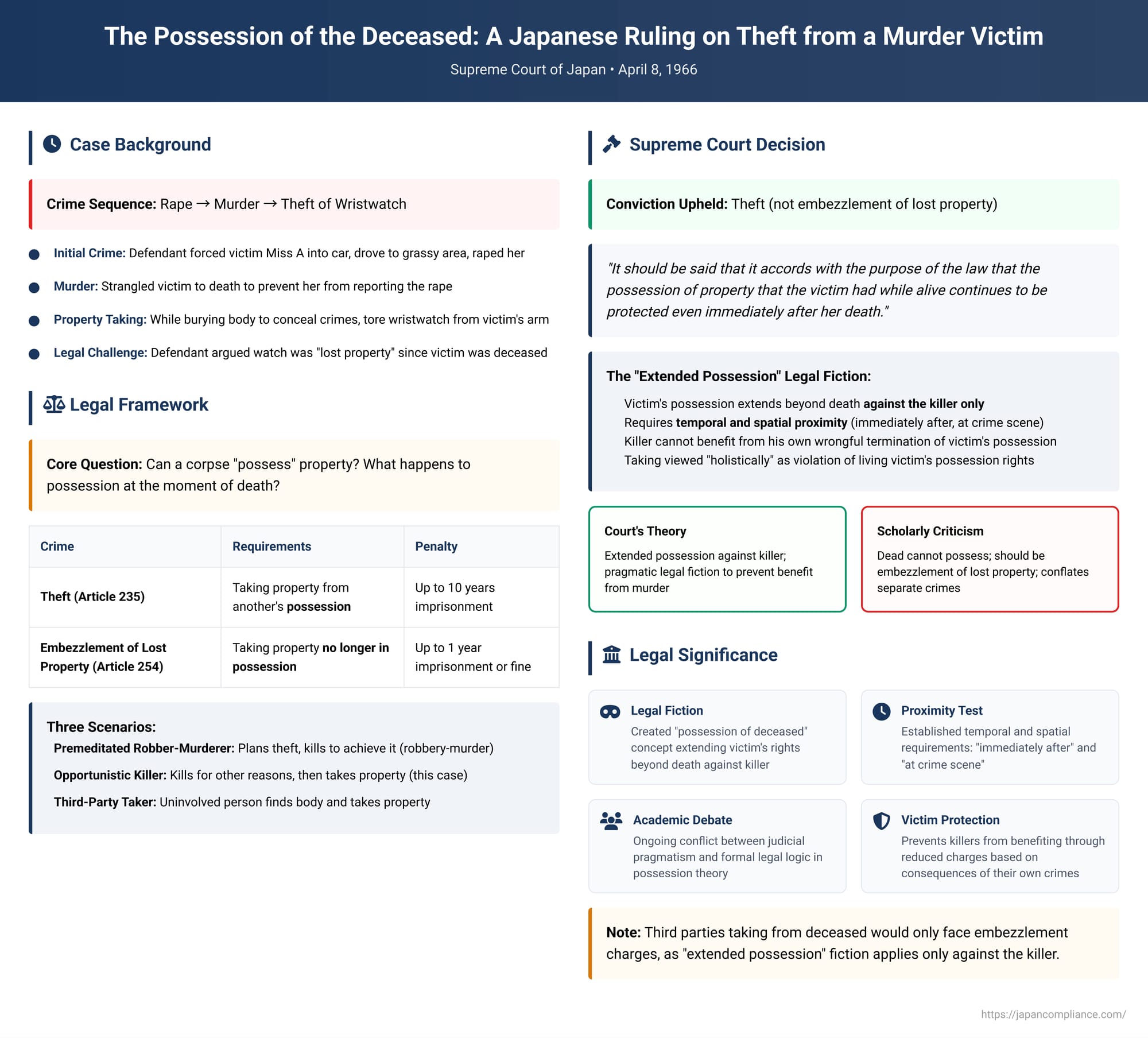

When a person dies, what happens to the property on their person? From a legal standpoint, can a corpse "possess" anything? This macabre but legally crucial question was at the center of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 8, 1966. The case concerned a defendant who, after raping and murdering a woman, took her wristwatch from her body. He argued that since she was dead, the watch was no longer in anyone's possession, making his act the lesser crime of embezzlement of lost property, not theft.

The Supreme Court rejected this argument. In a ruling that remains a cornerstone of Japanese criminal law, the Court established the legal concept of "possession of the deceased," a fiction that extends a victim's possession beyond the moment of death, but only as against the person who killed them. The decision delves into the complex relationship between homicide and property crime, drawing a fine, and still debated, line between theft and finding.

The Facts of the Case: From Rape and Murder to Theft

The facts of the case are grim. The defendant, while driving his car, saw a woman, Miss A, walking home. He forced her into his vehicle, took her to a nearby grassy area, and raped her. Fearing she would report the crime, he then murdered her by strangling her to death. In the process of burying her body to conceal his crimes, he tore a wristwatch from her arm and took it.

When prosecuted for a litany of crimes including rape, murder, and abandonment of a corpse, he was also charged with theft for taking the watch. His defense was a technical but significant legal argument: theft is the taking of property from another's possession. Since Miss A was deceased at the moment he took the watch, she no longer possessed it. Therefore, he argued, the watch was functionally "lost property," and he should only be guilty of the much lesser offense of embezzlement of lost property.

The Legal Problem: Three Scenarios of Taking from the Deceased

The defendant's argument highlighted a long-standing problem in criminal law. The legal classification of taking property from a deceased person depends heavily on the perpetrator's intent and their relationship to the victim's death. Legal analysis generally divides the issue into three distinct scenarios:

- The Premeditated Robber-Murderer: A person plans to steal from a victim and kills them as a means to that end. In this scenario, the law is clear: the crime is robbery-murder. The killing and the taking are seen as one unified act driven by a single criminal intent.

- The Opportunistic Killer (The Scenario in This Case): A person kills a victim for reasons other than theft (e.g., to silence them, out of rage) and only forms the intent to take property after the victim is already dead. This is the most legally contentious scenario.

- The Third-Party Taker: A person who had no involvement in the victim's death stumbles upon the body and takes property from it.

This case forced the Supreme Court to provide a definitive ruling for the second, most difficult scenario.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Legal Fiction to Bridge the Gap

The Supreme Court upheld the defendant's conviction for theft, rejecting his argument. The Court's reasoning, delivered in a parenthetical remark within its judgment, created a new and powerful legal fiction.

The Court acknowledged that the defendant did not initially intend to steal the watch and only formed the intent to do so after he had killed the victim. However, it emphasized the context: the taking happened "immediately after the criminal act, at the scene of the crime."

Based on this, the Court announced its core principle:

"In such a case, it should be said that it accords with the purpose of the law that the possession of property that the victim had while alive continues to be protected even immediately after her death."

The Court reasoned that because the defendant was "utilizing his own act that caused the victim to be separated from the possession of her property to then seize said property," his course of conduct, when "considered holistically," was an infringement of the victim's possession. In essence, the Court ruled that the victim's living possession is conceptually "extended" beyond the moment of death, but only as against the killer who wrongfully terminated that possession. The killer is estopped from benefiting from the legal consequences of the death he himself caused.

The Great Debate: Theft vs. Embezzlement of Lost Property

The Supreme Court's ruling, while providing a clear precedent, remains the subject of intense scholarly debate. The central conflict is between the Court's pragmatic legal fiction and a more logically rigid application of legal principles.

- The Court's "Extended Possession" Theory: This view, now the controlling precedent in Japan, focuses on the tight causal link between the killing and the taking. It requires strict temporal and spatial proximity—the taking must occur immediately after the death and at the same location. The theory's justification is that the killer should not be allowed to profit from his own homicidal act by having his subsequent property crime reduced to a lesser offense. However, critics point out that later court decisions have stretched the concept of "immediacy," especially in cases of indoor killings, sometimes upholding theft convictions for takings that occurred days later, arguably weakening the original test.

- The Prevailing Scholarly "Embezzlement" Theory: Many, if not most, legal scholars in Japan argue that the logically correct charge in this scenario is embezzlement of lost property. Their reasoning is direct and formalistic:Proponents of this view argue that the Court's ruling is an emotionally driven solution that conflates two separate crimes. The wrongfulness of the murder, they contend, should be punished fully by the murder charge, not used to artificially elevate a subsequent, and technically distinct, property crime from embezzlement to theft.

- A person cannot possess property when they are dead. Possession is a factual state of control that ends with life.

- At the moment the defendant formed the intent to steal, the victim was already deceased.

- Therefore, the property on her body was, by definition, "property separated from possession" (sen'yū ridatsubutsu).

- Taking such property precisely fits the definition of embezzlement of lost property.

The Final Piece: What About a Third-Party Taker?

To complete the legal picture, it is important to consider the third scenario. Here, both the Court's "extended possession" theory and the scholarly "embezzlement" theory reach the same conclusion. If a third party, who was not involved in the victim's death, discovers the body and takes the wristwatch, they would be guilty only of embezzlement of lost property. This is because there is no reason to "extend" the victim's possession as against someone who bears no responsibility for her death.

Conclusion

The 1966 Supreme Court decision on the "possession of the deceased" remains a vital and illustrative precedent in Japanese criminal law. It established that a killer who takes property from their victim as an afterthought, immediately and at the scene of the crime, is guilty of theft, not a lesser offense. It achieved this result by creating a legal fiction—that as against the killer, the victim's possession continues after death.

While this ruling provides what many consider to be an intuitively just outcome, it does so through a legally controversial framework that pits judicial pragmatism against theoretical purity. The case is a classic example of the law grappling with an extreme scenario, revealing the tension that can exist between formal legal definitions and the judiciary's pursuit of a result that aligns with broader societal notions of justice and culpability.