The Politician, the Regulator, and the Bribe: How Japan's High Court Defined 'Improper' Influence

In the complex interplay between government and industry, the line between legitimate advocacy and criminal influence peddling can be perilously thin. A company facing regulatory action might naturally seek the help of a politician to make its case. But when does that politician's intervention, especially when accompanied by a hefty payment, cross into a criminal attempt to subvert the course of justice? And what if the regulatory agency's decision is discretionary? Can pressuring an official not to take action ever be a crime if they had the legal right not to act in the first place?

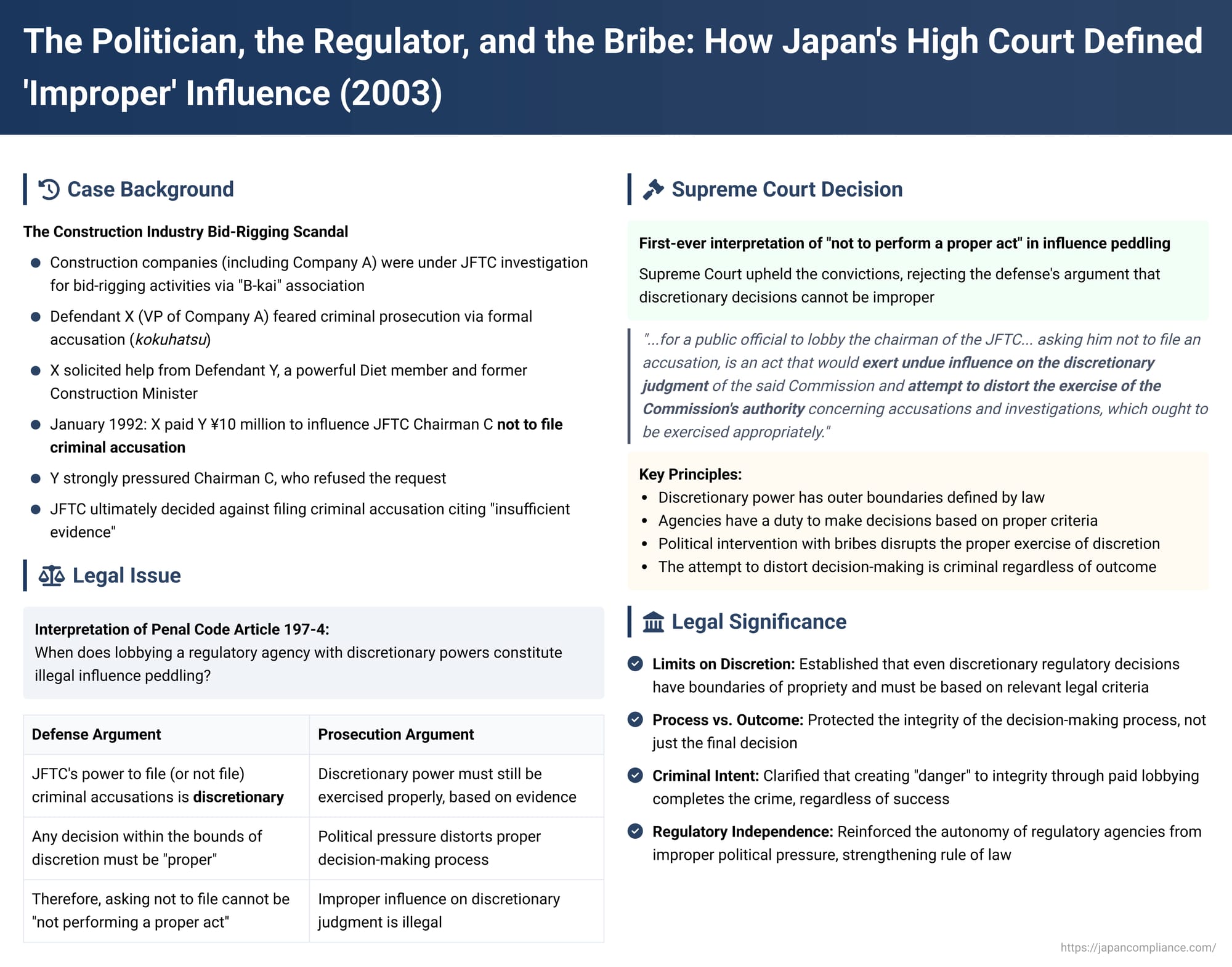

This sophisticated legal question was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on January 14, 2003. The case, arising from a major bid-rigging scandal in the construction industry, provided the Court's first-ever interpretation of a key clause in Japan's influence-peddling bribery statute, clarifying what it means to bribe a public official "not to perform a proper act."

The Facts: The Bid-Rigging Scandal and the Political Fixer

The case involved a classic scenario of industry seeking to evade regulatory enforcement through political channels.

- The Investigation: A number of construction companies, including Company A, were under investigation by Japan's Fair Trade Commission (JFTC). They were suspected of violating the Antimonopoly Act through bid-rigging activities organized via an association known as "B-kai."

- The Threat: The companies, represented by Defendant X (the vice president of Company A), feared that the JFTC would file a formal criminal accusation (kokuhatsu) with the Prosecutor-General, which would trigger criminal prosecutions.

- The Political Fixer: To prevent this outcome, Defendant X solicited the help of Defendant Y, a powerful member of the House of Representatives. Y was a former Minister of Construction and a high-ranking member of the ruling party's special committee on the Antimonopoly Act, making him an influential figure on this issue.

- The Bribe and the Request: In January 1992, at the Diet Members' Office Building, X formally requested that Y intervene on their behalf. The request was specific: Y was to use his political influence to persuade the JFTC Chairman, C, not to file the criminal accusation. Y accepted this request, and in return for his services, X gave him a bribe of 10 million yen in cash.

- The Aftermath: Following the payment, Y did, in fact, strongly pressure Chairman C to drop the case, but C refused the request. Ultimately, the JFTC decided not to file a criminal accusation due to what it deemed insufficient evidence, though it did issue a cease-and-desist recommendation to the companies involved.

The Legal Question: The Nature of a "Proper Act"

The defendants were charged with giving and accepting a bribe for influence peddling under Article 197-4 of the Penal Code. This statute is unique among Japan's bribery laws. It applies when a public official (the "influence peddler," like the Diet member) accepts a bribe in exchange for using their influence to lobby another public official (the "duty official," like the JFTC Chairman).

Crucially, to prevent abuse and protect legitimate political activity, the law limits the crime to situations where the influence is for the purpose of getting the duty official to "perform an improper act" or "not to perform a proper act" (shokumu jō sōtō no kōi o sezaru yō ni).

This created the central legal issue in the case.

- The JFTC's decision on whether to file a criminal accusation is generally understood to be a discretionary power. It is required to file an accusation when it "believes that a crime... has occurred," a determination that inherently involves judgment.

- The defense argued that if the JFTC has the discretion not to file an accusation, then choosing not to file cannot be a failure "to perform a proper act." Any choice within the bounds of discretion is, by definition, proper.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Distorting Discretion is Improper

The Supreme Court rejected the defense's argument and upheld the convictions. In its first-ever ruling on this specific clause, the Court established a powerful legal principle regarding discretionary authority. The Court held that:

"...for a public official, upon being solicited, to lobby the chairman of the JFTC regarding an investigation case... asking him not to file an accusation, is an act that would exert undue influence on the discretionary judgment of the said Commission and attempt to distort the exercise of the Commission's authority concerning accusations and investigations, which ought to be exercised appropriately. Therefore, it should be understood as constituting influence peddling 'to cause [an official] not to perform a proper act'..."

Analysis: The Limits of Discretion

The Court's decision brilliantly navigated the complexities of discretionary power. It did not deny that the JFTC has discretion. Instead, it focused on the integrity of the decision-making process.

- Discretion is Not Absolute: The ruling establishes that an official's discretion is not a shield against the law. While the final outcome of a discretionary decision may be flexible, the process for reaching that outcome is not.

- The Duty of Appropriate Judgment: A regulatory body like the JFTC has an overarching duty to exercise its discretion properly and based on relevant, legally sound criteria—in this case, the evidence gathered during its investigation. To make a decision based on outside political pressure or a bribe would be a violation of this duty.

- Lobbying as an Attempt to Distort: The act of lobbying, when backed by a bribe, is a criminal attempt to introduce an improper and corrupting factor into the agency's deliberations. It is an effort to distort the official's judgment and cause them to deviate from their duty to make an evidence-based decision. It is this attempt to cause a distortion that makes the lobbying an effort to get the official "not to perform a proper act."

- The "Danger" is Enough: The crime of influence-peddling bribery is complete when the influence is solicited and paid for. It creates a danger to the integrity of the regulatory process at that moment. It is irrelevant that the JFTC Chairman ultimately resisted the pressure or that the commission decided not to file an accusation for other reasons (insufficient evidence). The crime was in the corrupt attempt to influence the decision, not in the success of that attempt.

Conclusion

The 2003 Supreme Court decision in this major political corruption case provides a vital interpretation of what constitutes illegal influence peddling when directed at the discretionary powers of a regulatory agency. The ruling clarifies that even when an agency has the legal freedom to choose between different outcomes, it has an overriding duty to exercise that discretion appropriately and based on proper criteria. The case sends a powerful message that attempting to use bribes and political pressure to sway an official's discretionary judgment is a criminal act. The law protects not only the final outcome of a regulatory decision but also the integrity and fairness of the decision-making process itself from corrupting influence.