The Poisoned Sugar Case: A 1918 Ruling on When a Crime by Mail Begins

When does a murder attempt begin? If a killer sends a poisoned gift through the mail, is the crime already underway the moment the package is sent, or does the attempt only commence when it lands on the victim's doorstep? This question, concerning crimes committed at a distance through an innocent intermediary, was definitively answered by Japan's highest court over a century ago. The ruling, issued by the Supreme Court of Judicature (the predecessor to the modern Supreme Court) on November 16, 1918, established a clear and enduring principle for determining the "point of no return" in cases of indirect perpetration.

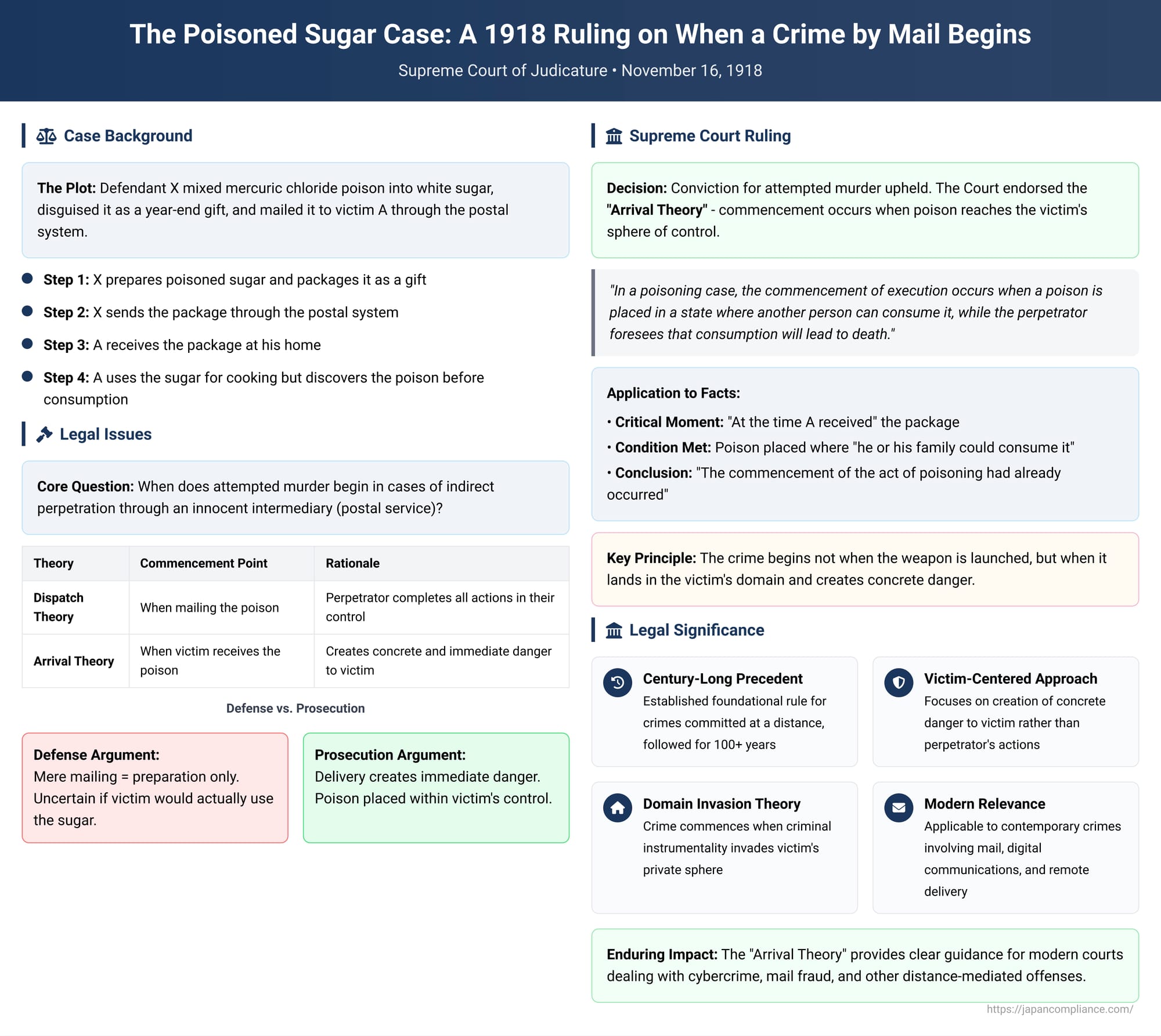

The Facts: A Gift of Poisoned Sugar

The facts of the case are as simple as they are chilling. The defendant, X, sought to kill his acquaintance, A. To achieve this, X mixed a lethal quantity of a potent poison, mercuric chloride, into a pound of white sugar. He then disguised the poisoned sugar as a traditional year-end gift and sent it to A as a parcel through the postal system. X fully foresaw that if A or his family consumed the sugar, believing it to be pure, they would die of poisoning.

The package arrived at A's home, and A received it, believing it to be a genuine gift. Sometime later, A was preparing a meal (a stew known as Satsuma-ni) and decided to use the sugar for seasoning. He took a spoonful and added it to the pot. However, upon doing so, he noticed an unusual reaction—the stew began to bubble strangely. This alerted him to the fact that something was wrong. He discovered the poison's presence before he or his family consumed any of the food, and the murder plot was foiled.

The defendant was tried and convicted of attempted murder. On appeal, his defense lawyer argued that the crime of murder had not yet commenced. The argument was that simply mailing the poisoned sugar was not enough; it was uncertain whether A would actually use it. Therefore, the act of mailing did not, by itself, place the victim in a state where he would inevitably consume the poison. It was, the defense contended, still mere preparation.

The Legal Debate: Dispatch vs. Arrival

This case brought to the forefront a classic legal debate in the context of "indirect perpetration"—where a perpetrator uses an innocent third party (here, the postal service) as an instrument to commit a crime. When does the attempt begin?

- The "Dispatch Theory" (利用者標準説 - riyōsha hyōjun setsu): This theory holds that the commencement of the crime occurs at the moment the perpetrator uses the intermediary. In this case, the attempt would have begun when X handed the parcel over to the post office. The perpetrator has done everything in their power, and the causal chain is set in motion.

- The "Arrival Theory" (到達時説 - tōtatsu jisetsu): This theory argues that the commencement occurs only when the criminal act reaches the victim's sphere of control, creating a direct and immediate danger. In this case, the attempt would begin when the poisoned sugar was delivered to and received by A.

The Court's Landmark Ruling

The Supreme Court of Judicature rejected the defense's argument and upheld the conviction. In its judgment, the court established a general principle that would guide Japanese law for the next century.

The court stated that in a poisoning case, the commencement of execution occurs when a poison is "placed in a state where another person can consume it," while the perpetrator foresees that consumption will lead to death.

Applying this principle to the facts, the court found that "at the time A received" the package, the poisoned sugar was "placed under a condition where he or his family could consume it." Therefore, the court concluded, "the commencement of the act of poisoning had already occurred."

With this reasoning, the court decisively endorsed the "Arrival Theory." The crime didn't begin when the weapon was launched, but when it landed.

A Century of Precedent: The Enduring "Arrival Theory"

The 1918 Poisoned Sugar case became the foundational precedent for crimes committed at a distance in Japan. For over 100 years, Japanese courts have consistently followed the "Arrival Theory," focusing not on the perpetrator's action but on the creation of concrete danger for the victim.

This principle is illustrated by other cases:

- Commencement Denied: In a later case, a defendant left poisoned juice on a rural path that his intended victims were known to use, hoping they would find and drink it. They did not, but another person did. The court ruled that the murder attempt against the intended victims had not commenced. Simply leaving the poison in a public place did not place it within the victims' sphere of control or create a sufficiently direct danger.

- Commencement Affirmed: In another early case involving a mailed extortion letter, the court ruled that the crime of attempted extortion began when the letter was delivered to the victim. At that point, the threat was placed in a state where the victim could become aware of it, creating the intended fear and thus initiating the crime.

The Theoretical Foundation: Invading the Victim's Domain

While the "Arrival Theory" is practical and intuitive, it poses a theoretical puzzle: how can the legal "commencement" of a perpetrator's crime happen at a time and place far removed from their own physical act? Legal scholars have debated this point for decades.

The older "Dispatch Theory" was criticized as being too formalistic. It focused entirely on the perpetrator's actions, even if the package was lost in the mail and no real danger ever materialized for the victim. The "Arrival Theory," conversely, focuses on the point where the risk becomes real.

A compelling modern justification for the "Arrival Theory" centers on the concept of invading the victim's domain. The crime's commencement is marked not by the perpetrator's act of "sending," but by the criminal instrumentality's act of "arriving." It is the moment when the perpetrator's criminal will crosses the threshold from the public sphere into the victim's private space—their home, their mailbox, their possession. This invasion creates a localized, concrete, and immediate danger that did not exist before, providing a solid theoretical and practical basis for marking the start of the criminal attempt.

Conclusion

The 1918 Poisoned Sugar case, though decided in a different era, remains a cornerstone of the modern law of criminal attempts. It provides a clear, principled, and enduring answer to the problem of crimes committed at a distance. By establishing the "Arrival Theory," the court wisely focused not on the perpetrator's last physical act, but on the moment their action created a tangible and imminent danger to the victim. The attempt begins not when the poisoned gift is sent, but the moment it is received, bringing the threat directly into the victim's life.