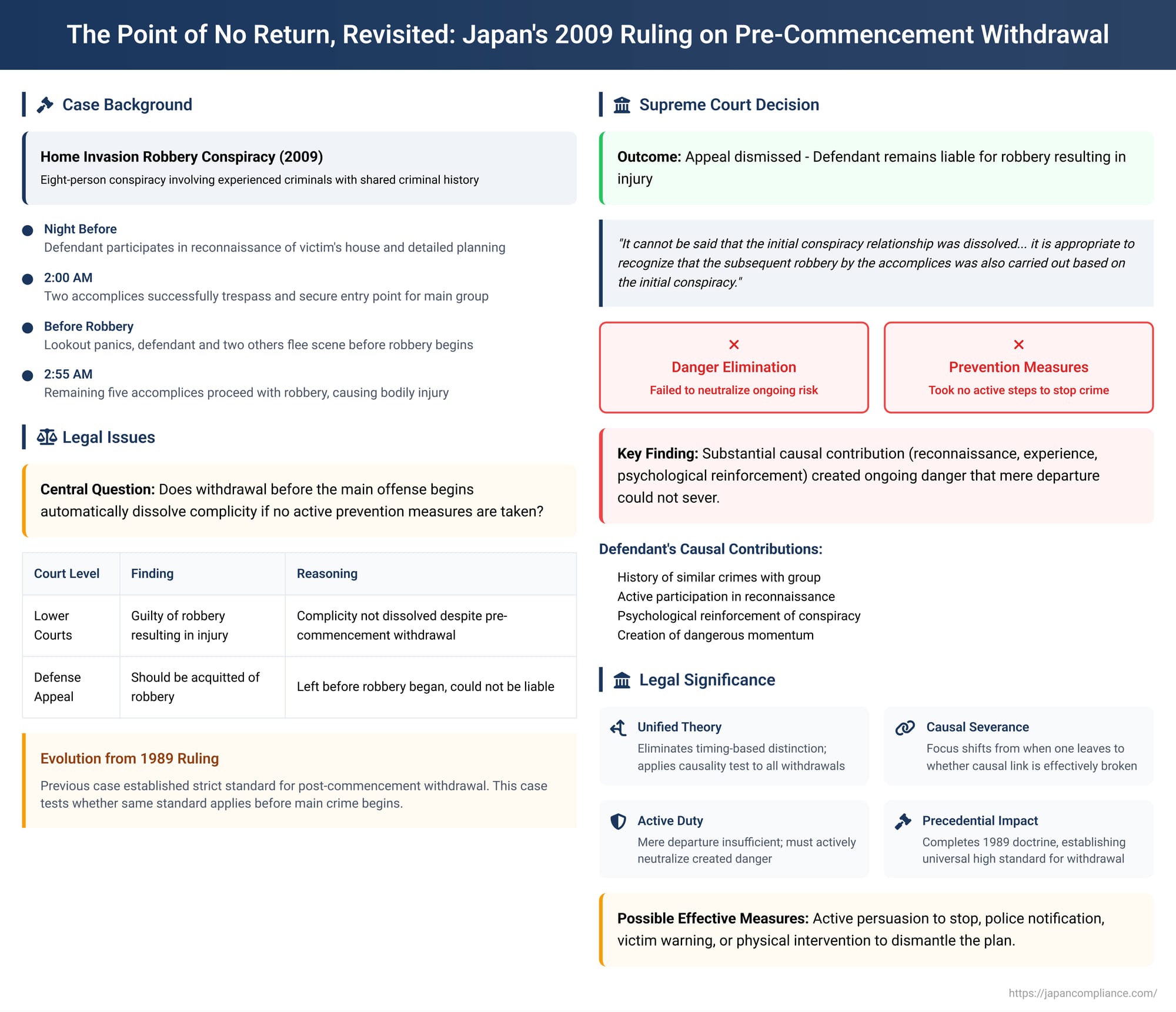

The Point of No Return, Revisited: Japan's 2009 Ruling on Pre-Commencement Withdrawal from a Conspiracy

Case Title: Jūkyo Shinnyū, Gōtō Chishō Hikoku Jiken (Case Concerning Trespass, Robbery Resulting in Injury)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Date of Judgment: June 30, 2009

Case Number: 2007 (A) No. 1580

Introduction: Redefining the Exit from a Criminal Plan

What does it truly take to walk away from a crime? The 1989 Supreme Court of Japan decision on dissolving a complicity relationship established a stringent standard: an accomplice who leaves mid-crime must take active steps to prevent the harm they helped set in motion. This ruling, however, left a critical question unanswered: does the same high bar apply to an accomplice who withdraws before the main offense even begins? Can a conspirator who gets cold feet during the planning or approach phase simply back out, or are they already bound by a causal chain of their own making?

This question was definitively answered two decades later in a landmark 2009 Supreme Court decision. The case involved a multi-person home invasion robbery where the defendant, a key participant in the planning, withdrew from the scene before the robbery itself commenced but after the initial trespass had occurred. The Court’s judgment is a powerful sequel to the 1989 ruling, effectively erasing the old, simpler distinction between pre- and post-commencement withdrawal. It solidified a universal principle in Japanese law: the key to severing liability is not when one leaves, but whether one has done enough to neutralize the specific danger they helped create.

Factual Background

The case involved a large-scale conspiracy with a complex series of events:

- The Conspirators and the Plan: The defendant was part of a group of eight individuals who conspired to commit a home invasion and robbery. The defendant was not a newcomer; he had a history of committing similar crimes with these same accomplices, establishing a significant level of mutual trust and experience within the group. The night before the planned invasion, the defendant drove to meet the others and actively participated in a reconnaissance of the victim's house and the surrounding area. The detailed plan was that once the lights in the house went out, two accomplices would breach the premises and open an entrance from the inside, at which point the defendant and the others would enter to commit the robbery.

- Partial Execution: On the night of the crime, around 2:00 AM, the plan was set in motion. Two accomplices successfully entered the property through a basement window. Finding the connecting door to the main residence locked, they briefly exited, had another accomplice unlock a different window, and re-entered, this time successfully unlocking the door from the inside to secure an entry point for the main group. At this stage, the crime of trespass was complete, but the robbery had not yet begun.

- The Withdrawal: While the defendant and another accomplice waited in a nearby car, ready to execute the robbery, the designated lookout panicked. Seeing people gathering near the scene, he feared discovery. He called the two accomplices inside the house and urged them to abort, saying, "People are gathering. You should give up and get out now." They responded, "Wait a little longer." The lookout refused, unilaterally stating, "It's too risky. I can't wait. I'm leaving first," before hanging up. He then got into the car where the defendant was waiting. The three of them—the defendant, the lookout, and the other waiting accomplice—discussed the situation and decided to flee together. The defendant then drove the car away from the scene.

- The Crime Continues: The two accomplices who were inside the house briefly came out and realized that the defendant and the two others had departed. However, they did not abandon the plan. Around 2:55 AM, they, along with three other accomplices who had remained at the scene, proceeded with the robbery as planned. During the robbery, they assaulted two of the home's occupants, causing them bodily injury.

The lower courts found the defendant guilty not only of the initial trespass but also as a co-principal in the subsequent crime of robbery resulting in injury (gōtō chishō). The reasoning was that despite leaving the scene, the defendant had failed to take any active measures to prevent the other accomplices from carrying out the robbery, and therefore the complicity relationship had not been dissolved. The defendant appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court upheld the lower court's conviction, delivering a judgment that would profoundly impact the doctrine of complicity in Japanese law. The Court found that even though the defendant withdrew before the robbery itself commenced, his initial complicity relationship remained intact, making him liable for the final outcome.

The Court's reasoning meticulously weighed the defendant's actions against his contributions to the criminal enterprise. It acknowledged that the defendant had left the scene, that this was before the robbery was initiated, and that the remaining accomplices became aware of his departure. However, these facts were not decisive.

Instead, the Court focused on what the defendant failed to do. It pointed out that after the lookout unilaterally announced his intention to leave, the defendant "did nothing more than to depart... without taking any particular measures to prevent the subsequent crime."

The Court found the defendant's initial involvement to be substantial. He had a history of similar crimes with the group, he joined the conspiracy, and he participated in the crucial reconnaissance. This created a strong causal link to the subsequent crime. His passive departure was insufficient to sever that link. The Court concluded that "it cannot be said that the initial conspiracy relationship was dissolved," and that "it is appropriate to recognize that the subsequent robbery by the accomplices was also carried out based on the initial conspiracy."

The ruling's most significant aspect is its application of this strict standard to a pre-commencement withdrawal. It signaled a major shift away from a simple, timing-based analysis toward a more holistic, causality-focused inquiry.

The Evolution of a Legal Doctrine: From Timing to Causality

The 2009 decision cannot be understood in isolation. It represents the culmination of a decades-long evolution in legal thought regarding the dissolution of complicity.

The Old "Timing-Based" Approach

For many years, lower court precedents suggested a relatively straightforward, timing-based distinction:

- Pre-Commencement Withdrawal: If an accomplice withdrew before the crime was put into execution, a clear expression of intent to withdraw, if accepted by the others, was often deemed sufficient to dissolve the conspiracy. The theory was that the agreement, the foundation of the conspiracy, was effectively rescinded.

- Post-Commencement Withdrawal: If withdrawal occurred after the crime had begun, a much higher standard was applied. Here, the withdrawing party had to take active steps to prevent the crime's completion, as a dangerous causal chain was already in motion.

This "timing-based indicator theory" (ridatsu jiki shihyō-ron) offered a clear, if somewhat mechanical, bright-line rule.

The 1989 Ruling: The Causality-Based Turning Point

The 1989 Supreme Court decision involving the joint assault marked a major shift toward the "causal severance theory" (inga-sei shadan-setsu). As that case involved a post-commencement withdrawal, it established that the accomplice had a duty to neutralize the danger he had helped create. His passive departure was insufficient. This ruling firmly grounded the analysis in causality but left open the question of whether the old, more lenient standard still applied to pre-commencement situations.

The 2009 Ruling: A Unified Theory

The 2009 decision resolved this ambiguity. By applying a strict, causality-based analysis to a pre-commencement withdrawal, the Supreme Court effectively declared that timing is no longer the dispositive factor. The ultimate question is always the same: Did the defendant's actions effectively sever the causal link between their contribution and the ultimate crime?

The Court demonstrated that a significant causal contribution can be made long before the main offense begins. The defendant's actions—leveraging his past criminal relationship, participating in reconnaissance, and agreeing to the plan—had already created a tangible momentum and a heightened risk of the crime's completion. The plan was not merely an abstract idea; it had been partially "objectified" when two accomplices, acting on the shared conspiracy, physically trespassed onto the property and prepared the way for the others. This created a dangerous situation that the defendant had a hand in building.

To escape liability, he needed to take active steps to dismantle it.

Analyzing the Defendant's Causal Contribution

The Court's conclusion rests on a deep analysis of the defendant's causal impact, which can be broken down into two components:

- Psychological Causality: The defendant was not a random newcomer. He was a trusted, experienced member of the crew. His agreement to participate and his presence during the planning and reconnaissance lent credibility to the enterprise and emboldened the other accomplices. This psychological reinforcement is a key causal factor in any conspiracy. The shared history created a strong bond of trust that made the plan more likely to succeed and harder to abandon.

- Physical Causality: While he did not enter the house himself, his participation in the reconnaissance was a direct physical contribution to the plan's execution. It provided essential information that facilitated the trespass and the planned robbery.

Given this substantial contribution, the risk of the remaining accomplices proceeding with the crime was high, even after the defendant's group departed. They had the know-how from the recon, a secured entry point, and the remaining members of the crew. The defendant simply leaving the scene did nothing to diminish this already-created danger. He effectively abandoned the dangerous situation he had helped to construct, making him responsible for the consequences.

What measures might have been sufficient? The ruling does not specify, but legal analysis suggests actions such as:

- Actively trying to persuade the remaining accomplices to abandon the plan.

- Calling the police to report the crime in progress.

- Taking steps to warn the victims.

These actions would represent a genuine effort to sever the causal link and prevent the harm, rather than simply saving one's own skin.

Conclusion: A Higher Standard for All

The 2009 Supreme Court decision is a crucial bookend to its 1989 ruling. Together, they establish a clear and unified doctrine on withdrawing from a criminal conspiracy in Japan. The simple act of walking away is not enough, regardless of the timing.

The law now demands a functional analysis: an accomplice's liability extends as far as their causal contribution. To terminate that liability, they must take active, preventative measures proportionate to their role in creating the criminal danger. The 2009 case makes clear that this duty can arise long before the primary crime is committed. By participating in the planning and preparation, an accomplice sets a causal chain in motion. To break that chain, they must do more than just step aside—they must endeavor to stop it.