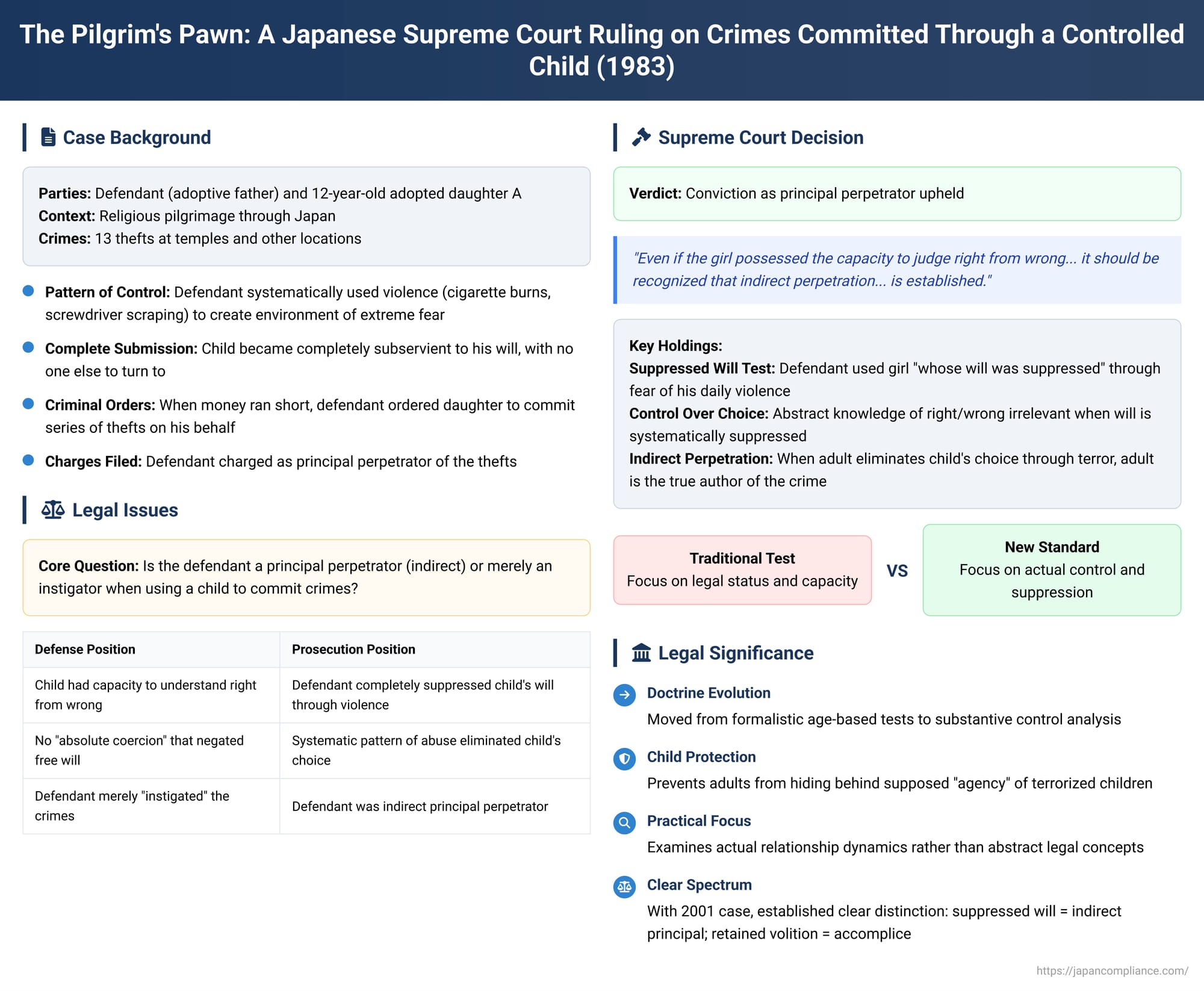

The Pilgrim's Pawn: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Crimes Committed Through a Controlled Child

When a person uses a child to commit a crime, who is the real criminal in the eyes of the law? Is the adult merely an "instigator" who encouraged the child's misdeeds, or are they the principal perpetrator, the true author of the crime itself? This question was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on September 21, 1983. The case, involving a man who forced his young adopted daughter to steal for him, provides a crucial definition of "indirect perpetration" (間接正犯 - kansetsu seihan) and establishes that the key factor is not the child's abstract knowledge of right and wrong, but the adult's absolute control over the child's will.

The Facts: A Pilgrimage of Fear and Theft

The facts of the case paint a disturbing picture of domination and abuse. The defendant was on a religious pilgrimage through Japan with his 12-year-old adopted daughter, A. This was not a journey of faith, but one of control. The defendant had a history of violence that had driven his wife from the home, leaving the young girl in his sole care. He cultivated an environment of extreme fear, systematically crushing any sign of defiance. Whenever A showed the slightest resistance, he would burn her face with a lit cigarette or scrape it with a screwdriver.

With no one else to turn to, the child became completely subservient to his will. When the defendant ran short of money on their trip, he turned his daughter into his criminal instrument. Over a period of several months, he ordered her to commit a series of 13 thefts at temples and other locations along their pilgrimage route, stealing cash and goods on his behalf.

The Legal Defense: An Instigator, Not a Thief?

The defendant was charged as the principal perpetrator of the thefts. His defense lawyer, however, put forward a nuanced legal argument. They did not deny that the defendant had ordered the girl to steal. Instead, they argued that his culpability should be limited to that of an "instigator" (教唆 - kyōsa), a role that is generally punished less severely than that of a principal perpetrator.

Their argument was based on the child's state of mind:

- A was 12 years old and, they claimed, possessed the capacity to understand that stealing was wrong.

- The defendant's commands did not amount to "absolute coercion" that would completely negate her free will in every moment.

- Therefore, she acted with a degree of her own agency.

Since the defendant had merely "used" a person who was capable of making her own moral judgments, he should be seen as an instigator who prompted her illegal acts, not as the principal thief himself.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Control is the Key

The Supreme Court of Japan unequivocally rejected this argument and affirmed the defendant's conviction as the principal perpetrator. The Court's reasoning cut through the defense's claims about the child's abstract knowledge and focused instead on the stark reality of their relationship.

The Court highlighted the defendant's pattern of violence—the cigarette burns and the screwdriver—as the foundation of his control. It found that he had systematically used these acts to make the child obey his every command. Based on this, the Court delivered its key holding:

The defendant "used" the girl, who was "in fear of his daily conduct and whose will was suppressed," to carry out the thefts. Therefore, "even if the girl possessed the capacity to judge right from wrong... it should be recognized that indirect perpetration... is established."

In essence, the Court ruled that the defendant's complete suppression of the child's will was the legally decisive factor. Her ability to intellectually distinguish right from wrong was irrelevant in the face of the terror that governed her actions.

The Evolution of a Doctrine: A Substantive Test of Control

This 1983 ruling was a landmark because it solidified a modern, substantive approach to indirect perpetration, moving away from older, more formalistic standards. Previously, some interpretations had focused almost exclusively on the legal status of the person being used—if they were under the age of criminal responsibility (14 in Japan), the user was automatically the indirect principal.

This case established that the true test is the actual state of control and suppression of will. This principle was further clarified by a contrasting Supreme Court decision in 2001. In that case, a mother persuaded her reluctant 12-year-old son to commit a robbery. The court found that this was not indirect perpetration. The mother had used persuasion, not a campaign of terror. The son, while influenced, ultimately acted with his own volition and adapted to the situation as it unfolded. The mother was convicted not as an indirect principal, but as a co-perpetrator with her son.

Together, these two cases create a clear and practical spectrum in Japanese law:

- Suppressed Will (The 1983 Pilgrim Case): When a person uses violence and fear to crush the will of a minor, they are the indirect principal.

- No Suppressed Will (The 2001 Mother-Son Case): When a person merely persuades or encourages a minor who retains their own volition, they are an accomplice (either a co-perpetrator or an instigator).

The degree of suppression required does not have to be "absolute" in the sense of a hypnotic trance. As this case shows, a sustained pattern of abuse, combined with the victim's youth, isolation, and dependency, is sufficient to establish the level of control needed for a finding of indirect perpetration.

Conclusion

The 1983 "Pilgrim's Pawn" case is a foundational decision in the Japanese law of complicity. It powerfully defines perpetration not by who physically performs the criminal act, but by who truly controls the criminal will. The ruling teaches that one cannot hide behind the supposed "agency" of a child when that agency has been systematically eroded by fear and violence. The Supreme Court looked past the child's hands that committed the thefts and saw the defendant's will as the true and only moving force behind the crime. It established, with resounding clarity, that in the eyes of the law, the master of the puppet is the true author of its deeds.