The Phantom Residence: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Arson of a 'Sham' Home

Imagine a house that is not a home. It is a stage, fully furnished and equipped, where people are paid to sleep overnight, all to create the illusion of habitation for a fraudulent purpose. Now, imagine the orchestrator of this sham secretly removes the "inhabitants" for a few days and, in their absence, has the house burned to the ground. Has he committed the grave crime of destroying an "inhabited building," or did he merely destroy an empty stage set?

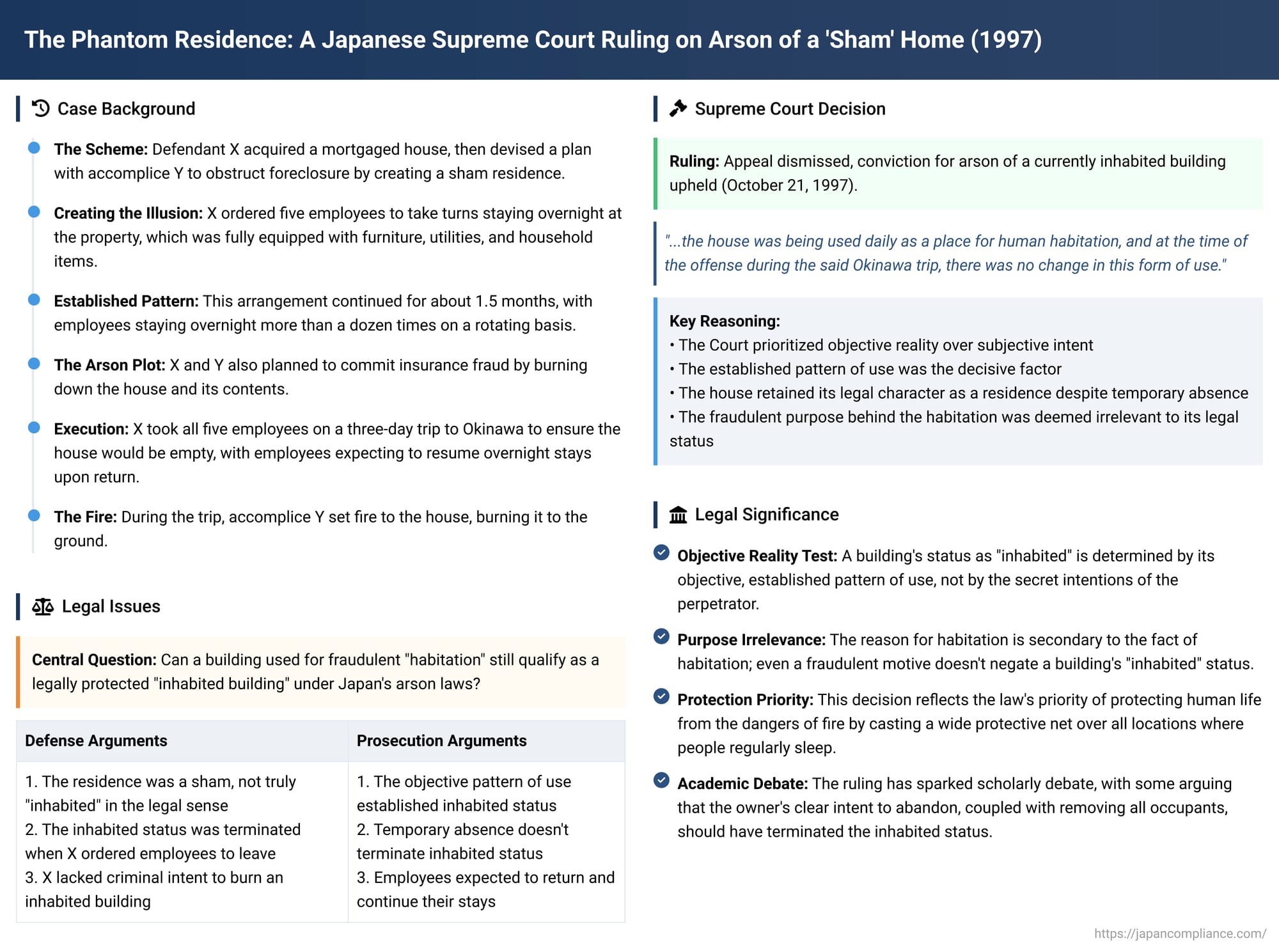

This bizarre and complex scenario was not a work of fiction but the subject of a fascinating and pivotal ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on October 21, 1997. The case forced the Court to probe the very definition of a "residence" and question whether a building's protected status as a "home" depends on the subjective intent of its occupants or the objective reality of its use, even when that use is a carefully constructed deception.

The Facts: A Conspiracy of Fire and Deception

The case involved a defendant, X, who had acquired a house with an existing mortgage for the purpose of resale. When foreclosure proceedings began, X, along with an accomplice, Y, devised a plan to obstruct the auction.

- Creating a Sham Residence: To create the appearance that the house was occupied, which could be used to claim residency rights and hinder the sale, X ordered five of his employees to take turns staying overnight at the property.

- The Setup: The house was fully equipped for daily life, with a bath, kitchen, toilet, and utilities like water, gas, and electricity. It was furnished with beds, bedding, tables, a refrigerator, a television, and other household items. Employees were given keys and could come and go freely.

- An Established Pattern: This arrangement continued for about a month and a half, during which employees stayed overnight more than a dozen times on a rotating basis. To neighbors, it appeared as though people had genuinely moved into the house.

- The Arson Plot: In parallel, X and Y conspired to commit insurance fraud by burning down the very same house and the household goods they had placed inside it.

- The Final Act: To ensure the house would be empty for the arson, X took all five employees on a three-day trip to Okinawa. He told the employees scheduled to be at the house that they did not need to stay during the trip. This was done specifically so they would not become aware of the arson plan. While they were away, accomplice Y set fire to the house, burning it to the ground.

Crucially, X never told the employees that the overnight stays were permanently over. The employees fully expected that, upon their return from Okinawa, they would resume their rotating shifts of staying at the house. The keys to the house were never collected from them; one employee even took a key with them on the trip.

A Three-Tiered Defense

When charged with arson of a currently inhabited building, X's defense presented a multi-layered argument:

- The Residence Was a Sham: They argued the house was never truly "inhabited" in the legal sense. The overnight stays were not for the purpose of daily living but were part of a ruse to obstruct a legal proceeding. It was not a genuine home.

- The Inhabited Status Was Terminated: Even if the house had achieved "inhabited" status, that status was extinguished when X, the person in control, ordered the employees to leave for the trip with the secret intention of destroying it.

- Lack of Criminal Intent: Since X had personally ensured the building was empty and believed its inhabited status was terminated, he could not have had the necessary intent (koi) to burn an inhabited building, which is a key element of the crime.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Objective Reality Over Subjective Intent

The Supreme Court unanimously rejected the appeal and upheld the conviction for the more serious crime. The Court's reasoning focused on the objective reality of the situation, effectively looking past the defendant's secret motives and plans. The Court declared:

"...the house was being used daily as a place for human habitation, and at the time of the offense during the said Okinawa trip, there was no change in this form of use."

In the Court's view, the established, observable pattern of use was the decisive factor. Because this pattern had been ongoing and the employees expected it to continue, the house retained its legal character as a residence, even during the temporary, orchestrated absence of its occupants.

Analysis: A Deep Dive into the Meaning of "Inhabited"

This decision delves into some of the most nuanced aspects of arson law, particularly the question of what makes a building a "home" and when that status is lost.

- Does the Purpose of Habitation Matter?: The Court's decision implicitly confirms that the reason for habitation is secondary to the fact of habitation. Precedent has long held that places not used for traditional family life, such as overnight duty rooms, can be considered "inhabited". The objective fact that people were regularly sleeping and using the house's facilities was sufficient, regardless of the fraudulent motive behind it.

- Whose Intent Defines the Home?: This is the most complex and debated aspect of the case. The central conflict is between the arsonist's subjective intent to abandon the residence and the "inhabitants'" belief that their residency would continue.

- The Court's Perspective (Objective Use): The Supreme Court prioritized the objective state of affairs. The house was equipped for living, a pattern of use was established, and the users (the employees) had every reason to believe it would continue. In the absence of an explicit, permanent termination of this arrangement, the "form of use" remained unchanged. This maintains a strong, protective standard for any location that objectively serves as a human dwelling.

- A Critical Counter-Argument: Some legal scholars have raised powerful counter-arguments. The employees' "residency" was entirely artificial and dependent on X's orders. Their intent to return was based on a deception. X, by planning the arson, had effectively revoked his own order to inhabit the house. His act of taking them on the trip was the physical manifestation of his decision to terminate the building's inhabited status so it could be destroyed. Punishing him for burning an "inhabited" building when he took every conceivable step to ensure it was un-inhabited seems paradoxical. This view argues that the owner's clear intent to abandon, coupled with the removal of all occupants, should terminate the inhabited status.

Conclusion

The 1997 "Phantom Residence" case is a profound lesson in the Japanese legal system's approach to property crimes. It establishes that a building's status as an "inhabited" dwelling is determined by its objective, established pattern of use, not by the secret, uncommunicated intentions of an arsonist—even when that arsonist is the one who created the pattern of use in the first place. The law, in its mission to protect human life from the dangers of fire, casts a wide protective net. Once a building takes on the objective characteristics of a home where people regularly sleep, it is afforded the law's highest protection. An offender cannot easily strip a building of that protected status through temporary, deceptive maneuvers designed to facilitate its destruction.