The Perils of "Signature Agency" in Japanese Notarial Deeds: Supreme Court's Stance on Validity

In Japan, a "notarial deed" (公正証書 - kōsei shōsho), particularly one containing an "execution undertaking clause" (執行受諾文言 - shikkō judaku mongon), can serve as a powerful "title of obligation" (債務名義 - saimu meigi). This allows a creditor to proceed directly to compulsory execution without first obtaining a court judgment if the debtor defaults. Given the significant legal power of these "execution deeds," Japanese law, specifically the Notary Act, imposes strict procedural requirements for their creation.

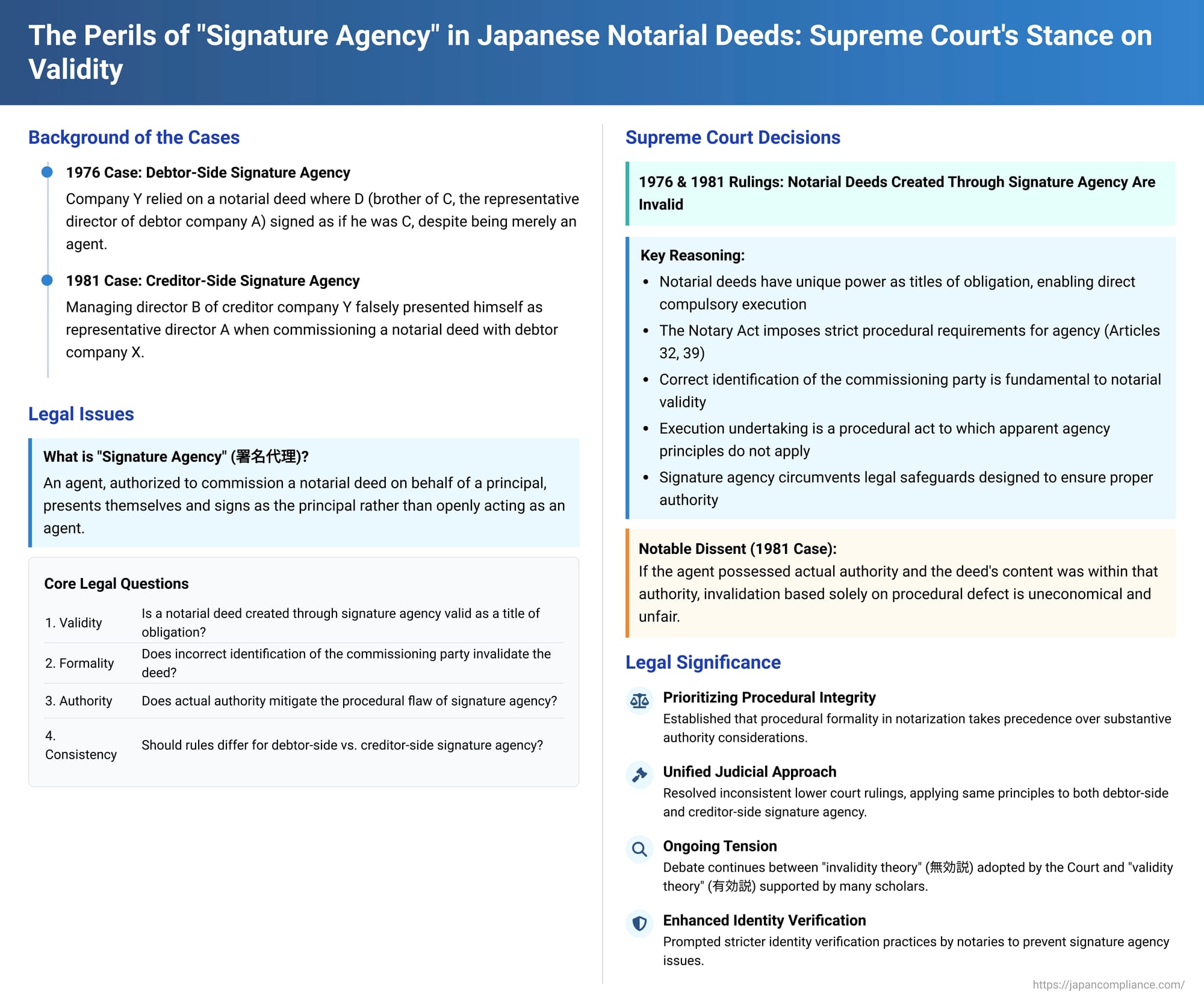

A critical issue arises when an agent, authorized to commission the creation of a notarial deed on behalf of a principal, does so by presenting themselves and signing as the principal, rather than openly acting as an agent. This practice is sometimes referred to as "signature agency" (署名代理 - shomei dairi). Two key Supreme Court decisions from 1976 and 1981 grappled with the validity of notarial deeds created under such circumstances, establishing a generally strict stance that prioritizes procedural formality.

Case 1: Debtor-Side Signature Agency (Supreme Court, October 12, 1976)

Case Name: Action of Objection to Distribution (Showa 50 (O) No. 918)

Decision Date: October 12, 1976

Facts:

Company X held a judgment against Company A and sought to attach Company A's bank deposits. However, Company Y had previously attached the same deposits based on an execution deed—a notarial debt payment agreement created between Y and A. The bank deposited the disputed funds with the court, which then prepared a distribution plan favoring Y. X objected, arguing that the notarial deed Y relied upon was invalid.

The alleged invalidity stemmed from how the deed was commissioned. C, the representative director of Company A, was absent. D (C's younger brother), who had received instructions from C to create the notarial deed and was given the necessary documents (including seal certificates), went to the notary's office. Instead of acting in the capacity of an agent for C, D signed the deed as "C" himself, using Company A's seal that C had entrusted to him. X argued this "signature agency" rendered the notarial deed procedurally defective and therefore void as a title of obligation.

The District Court and the High Court sided with X, invalidating Y's portion of the distribution and ordering a revised plan. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning:

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions that the notarial deed was invalid. The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Importance of Notarial Deeds: A notarial deed, by itself, becomes a title of obligation without needing court proceedings, enabling creditors to initiate compulsory execution once a certificate of execution is obtained. Therefore, for a notarial deed to have such "notarial effect" (公正の効力 - kōsei no kōryoku), it must meet the requirements stipulated by law (Notary Act, Article 2).

- Strict Procedural Requirements for Agency: When a notarial deed is commissioned by an agent, the Notary Act mandates specific procedures:

- Submission of documents proving agency authority and seal certificates (Notary Act, Article 32).

- The notary must notify the principal of the agent's name and other prescribed matters (Notary Act Enforcement Regulations, Article 13-2).

- The notary must read the prepared deed to, or allow its inspection by, those present, who must then individually sign and seal it (Notary Act, Article 39).

- Purpose of Requirements: The Court emphasized that the purpose of these regulations, given the importance of notarial deeds, is to ensure that they are commissioned by individuals with legitimate authority and that their contents are true.

- Fundamental Nature of Identity: The correct identification of the person actually commissioning the deed is a most fundamental requirement in its creation. Signatures are a crucial method for identifying the actor.

- Execution Undertaking as a Procedural Act: The "execution undertaking" (the debtor's statement consenting to execution if they default) contained in a notarial deed is a procedural act directed towards the notary. Crucially, the Court reiterated a prior ruling (Supreme Court, May 23, 1958) stating that the Civil Code provisions on apparent agency (表見代理 - hyōken dairi), which aim to protect relying parties in private transactions, do not apply or apply mutatis mutandis to such procedural acts.

- Signature Agency Circumvents the Law: Therefore, in the case of a notarial deed commissioned by an agent, the procedures stipulated in the Notary Act must be followed, and the agent commissioning the deed must sign it themselves (as an agent). An agent commissioning the deed by posing as the principal circumvents these provisions. Such a commission is illegal, and a notarial deed created based on it cannot produce any notarial effect. There is no room to recognize signature agency.

Applying this to the facts, C, the representative of the debtor Company A, did not appear before the notary. D, C's agent, commissioned the deed but did not follow the prescribed agency procedures, instead posing as C and signing as C. The Supreme Court concluded the commission was illegal, and the notarial deed had no notarial effect, thus being invalid as a title of obligation.

Case 2: Creditor-Side Signature Agency (Supreme Court, March 24, 1981)

Case Name: Action of Objection to Claim (Showa 53 (O) No. 203)

Decision Date: March 24, 1981

Facts:

Company X (lessee) and Company Y (lessor) entered into a building lease agreement, in connection with which a notarial deed was created. This deed included an execution undertaking clause stating that if X failed to pay rent, Y could immediately proceed to compulsory execution without prior notice. When X fell into arrears, Y initiated execution based on this deed. X filed an action of objection to claim, arguing the deed was invalid.

The ground for invalidity was, again, signature agency, but this time on the creditor's side. X alleged that when the notarial deed was commissioned, B, the managing director of the creditor Company Y, had falsely presented himself as A, the representative director of Company Y. X argued such a deed lacked proper formality and thus had no notarial effect.

The trial court (Osaka District Court) initially dismissed X's claim. It found that X's representative knew about Y's signature agency but raised no objection, leading the notary to mistakenly believe B was A. In such circumstances, the court held the deed was not necessarily invalid. However, the High Court (Osaka High Court) reversed this decision. It reasoned that the validity of a notarial deed should not differ based on whether the procedural violation occurred on the creditor's or debtor's side, citing the 1976 Supreme Court decision (Case 1). The High Court held that execution based on the deed was impermissible. Company Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court's Majority Decision and Reasoning:

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the High Court's judgment. The majority's reasoning was concise:

The principle established by the Court's precedent (referring to the 1976 decision regarding debtor-side signature agency) that such a deed has no notarial effect and is invalid as a title of obligation, applies equally when an agent of the creditor commissions the deed by posing as the creditor and signing the creditor's name.

Dissenting Opinion:

One Justice offered a dissenting opinion, arguing for the validity of the deed under certain conditions:

- If the agent (B, in this case) was actually granted authority by the creditor-principal (A) to commission the notarial deed, and the content of the created deed was within the scope of that granted authority, then the notarial deed should be considered valid as a title of obligation.

- While the Notary Act sets forth strict procedural rules for agency (Articles 31, 28, 32, 39; Enforcement Regulations Article 13-2) to ensure deeds are commissioned by those with proper authority and that their contents are true, thereby enhancing public trust, these procedures must indeed be followed.

- However, if a deed has already been created, and the flaw is that the creditor's agent concealed their agency and signed as the principal, it is inappropriate to invalidate it solely for this procedural defect if the agent genuinely possessed the authority and the deed's content was within that authority.

- Invalidating such deeds, as the majority did, would be uneconomical (requiring the parties to go through the process of creating a new, identical deed) and would unfairly benefit the debtor, which goes against the principle of fairness.

Significance and Analysis of the Decisions

These Supreme Court rulings, along with a third decision on the same day as Case 2 (March 24, 1981, Hanrei Jihō No. 999, p. 56, which invalidated a deed where a sub-agent signed as the primary agent), clearly established the Supreme Court's consistent position: notarial deeds created through signature agency are invalid as titles of obligation. This stance unified previously inconsistent lower court judgments, some of which had found deeds valid, especially in cases of creditor-side signature agency.

1. The Prevailing "Invalidity Theory" (無効説 - mukō setsu)

The Supreme Court's decisions firmly adopted what is known as the "invalidity theory." The core arguments supporting this theory, as reflected in the judgments and legal commentary, include:

- Strict Procedural Adherence: The notary's power to examine the legality of the transaction is primarily focused on procedural propriety and limited in its ability to delve into substantive validity unless specific doubts arise. This limitation places a higher premium on the meticulous observance of formal procedures, especially those concerning agency as laid out in the Notary Act (Articles 2, 28, 32, 39). Overlooking such formalities (condoning a mismatch between form and substance) is deemed unacceptable given the significant power of a notarial deed to initiate compulsory execution.

- Execution Undertaking as a Procedural Act: The debtor's execution undertaking is considered a procedural act toward the notary. The established judicial precedent that principles of apparent agency (which protect parties in private substantive law transactions) do not apply to such acts is a key justification.

- Systemic Integrity and Prevention of Abuse: Allowing signature agency could lead to laxity in verifying the identity of the commissioning party. Notaries might become less diligent, and agents might be tempted to bypass the more cumbersome procedures required for proving agency. This could result in an increase in notarial deeds where the true commissioning party is unclear, undermining the Notary Act's objective of preventing unauthorized commissions.

- Avoiding Instability: If signature agency by an authorized agent were deemed valid, it might become difficult to deny validity if an unauthorized agent did the same and the principal later attempted to ratify the act, leading to legal instability.

2. The "Validity Theory" (有効説 - yūkō setsu) – The Dissenting View and Scholarly Support

Despite the Supreme Court's stance, many legal scholars and the dissenting opinion in the 1981 case favor the "validity theory," particularly when the agent genuinely possessed the authority from the principal. Their arguments include:

- Analogy to Private Law: In general private law transactions, an act performed by an agent who signs as the principal can be valid if the agent was authorized to act in that specific manner. To require parties to create a new deed or obtain a separate title of obligation when the substantive agreement and authority exist is often seen as overly burdensome and economically inefficient.

- Purpose of Notary Act Formalities: The strict agency rules in the Notary Act are intended to ensure that deeds are commissioned by legitimately authorized individuals, thereby guaranteeing the truthfulness of the deed's content. If an agent who actually has the requisite authority performs the commission, invalidating the deed solely due to a flaw in the form of representation (i.e., signing as principal instead of as agent) may not align with the underlying purpose of these rules, especially if the content of the deed accurately reflects the principal's intentions and the scope of the agent's authority.

- Nature of Execution Undertaking: While the execution undertaking is a procedural act, it is typically an integral part of a substantive contractual agreement recorded in the notarial deed. Arguing for a sharp distinction between the two for the purpose of validity can be questioned.

- Potential for Abuse by Debtors: The invalidity theory can be exploited by debtors seeking to delay or evade rightful execution.

- Inapplicability of Apparent Agency Precedent: The Supreme Court's reliance on the non-applicability of apparent agency to procedural acts is critiqued. Apparent agency deals with situations where the "agent" lacks actual authority, and the rule protects third parties who reasonably believed authority existed. Signature agency, in contrast, often occurs where the agent does have actual authority but fails to disclose their status. Thus, the preclusion of apparent agency (which addresses unauthorized agency) is not necessarily a strong reason to invalidate acts of authorized agents who merely use an improper form.

- Behavioral Norms vs. Post-Facto Validity: The strict rules for agency in the Notary Act can be seen as "behavioral norms" that should be followed during the creation of the deed. However, if a deed is already created and a defect like signature agency is discovered, its validity in subsequent litigation (e.g., an action of objection to claim) could arguably be assessed with more consideration for the substantive realities, such as the existence of actual authority.

3. Evaluation and Balancing Interests

The Supreme Court's majority opinions prioritize the integrity and reliability of the notarial system by insisting on strict adherence to formal procedures. From the notary's perspective, who has limited powers to investigate substantive rights, the correct identification of the commissioning party is paramount. Any deception or error in this regard is seen as a fundamental flaw in the procedure, justifying invalidation. This perspective views the matter as transcending a simple balancing of interests between the immediate parties and touching upon the foundational trust in the public institution of notarization.

However, as highlighted by the dissenting opinion in the 1981 case and supporting academic views, when a notary fails to detect signature agency despite the agent possessing actual authority, a rigid application of the invalidity rule can lead to outcomes that seem misaligned with the substantive agreement between the parties. It can impose significant economic and time burdens on the party who rightfully expected a valid deed, potentially leading to the very execution delays the system seeks to avoid. The argument is that the focus should be on protecting the legitimate interests of the parties involved, and if the substantive requirements (like actual agency authority) are met, procedural missteps that don't harm the other party or public order shouldn't automatically void the entire instrument.

4. The Role of Notary's Identity Verification Practices

Ultimately, the problem of signature agency often arises from a failure in the notary's identity verification process. If notaries employ more rigorous methods to confirm the identity of individuals commissioning deeds and their capacity (principal or agent), the incidence of undetected signature agency could be significantly reduced.

There have long been proposals to enhance these verification methods, such as requiring notaries to ask explicitly whether a person is commissioning as a principal or an agent, and demanding photo identification documents (e.g., My Number Card, driver's licenses, passports) in addition to traditional seal certificates and seals. Current notary practices in Japan appear to be moving towards stricter identity verification, incorporating such measures. Legislative amendments to explicitly require such measures in the Notary Act (e.g., Article 28) have also been suggested. Such advancements in identity verification could make the "correct identification of the commissioning party" more reliably achievable, thereby potentially mitigating the frequency and impact of signature agency disputes.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court has taken a firm stance that notarial deeds created through "signature agency"—where an authorized agent signs as the principal—are procedurally flawed and lack notarial effect, rendering them invalid as titles of obligation. This approach emphasizes the paramount importance of strict adherence to the Notary Act's procedural requirements to safeguard the integrity and public trust in the notarial system.

However, this "invalidity theory" is not without its critics, particularly in situations where the agent possessed actual authority and the content of the deed was within that authority. Dissenting opinions and significant academic commentary argue for a more substance-oriented approach in such cases, pointing to potential inequities and inefficiencies. As notary practices for identity verification continue to evolve and strengthen, the practical dilemmas posed by signature agency may lessen, but the tension between procedural strictness and substantive fairness in this context remains a noteworthy aspect of Japanese civil execution law.