The Paradox of Stopping Too Soon: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Preparation vs. Attempt

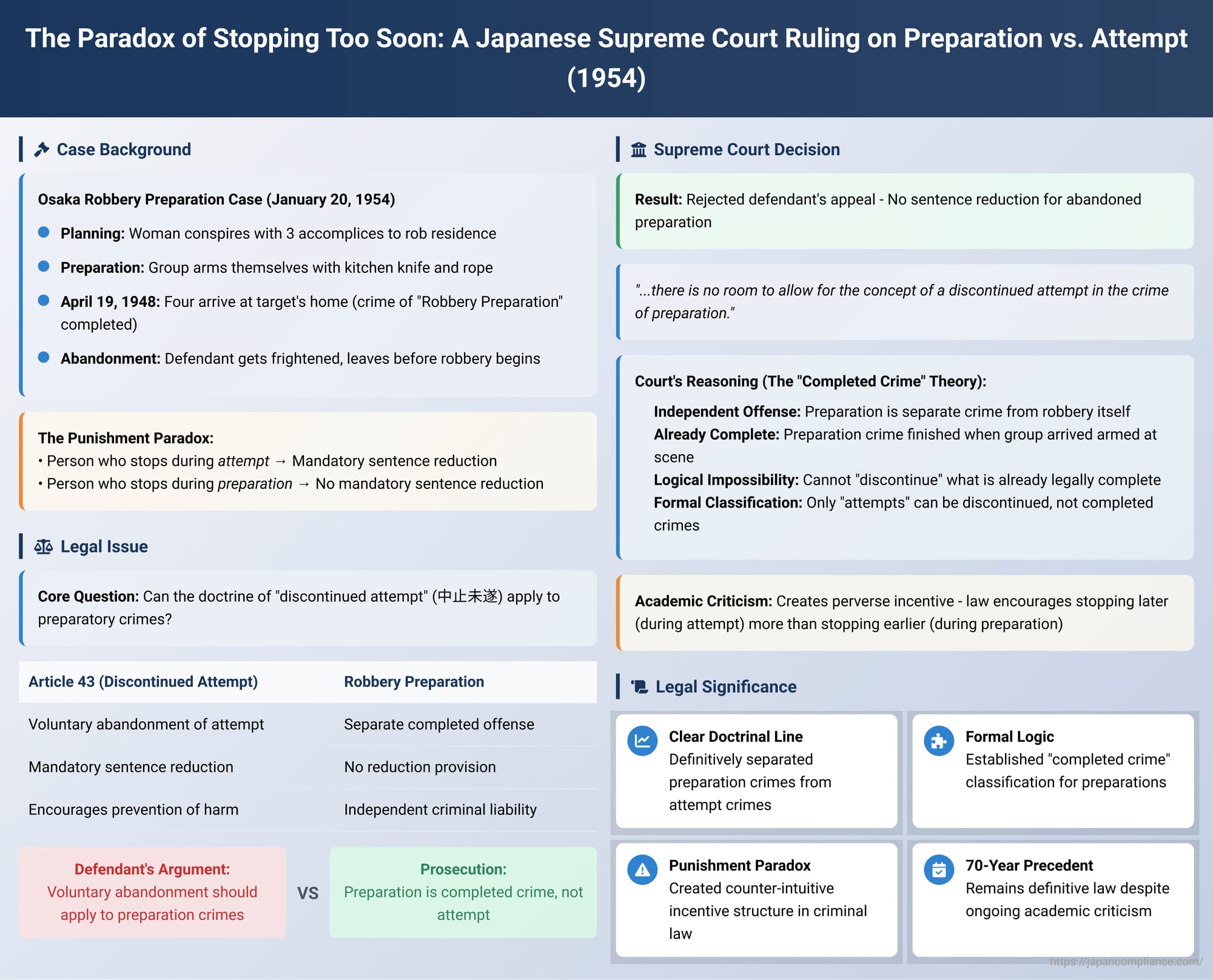

Which criminal is more deserving of leniency: the one who begins a robbery but has a change of heart midway through, or the one who prepares for the same robbery, goes to the scene, but gets scared and leaves before ever starting? Intuition suggests the person who stops earlier is more commendable. Yet, under a long-standing principle of Japanese law, it is the person who stops later who receives a mandatory reduction in their sentence, while the one who stops earlier does not.

This legal curiosity, known as the "punishment paradox," was cemented by a landmark decision from the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on January 20, 1954. The case drew a sharp and definitive line between a criminal preparation and a criminal attempt, establishing a formalistic logic that has been the law of the land for over 70 years.

The Facts: A Robbery Abandoned

The case involved a woman who conspired with three accomplices to commit a robbery at a residence in Osaka. In preparation, the group armed themselves with a heavy kitchen knife and a rope. On the evening of April 19, 1948, the four went together to the target's home. Under Japanese law, the act of preparing weapons and proceeding to the scene with the intent to commit robbery constitutes the crime of "Robbery Preparation" (強盗予備 - gōtō yobi).

However, the robbery itself never happened. The defendant claimed that she had only guided the others to the location and, upon seeing her accomplices knocking on the door, became frightened and went home. Based on this, she made a crucial legal argument on appeal.

The Legal Question: Can You "Abandon" a Preparation?

The defendant argued that even if she were guilty of preparing for a robbery, her act of leaving the scene should be considered a "voluntary abandonment" of the crime. She asked the court to apply the legal doctrine known as "discontinued attempt" (中止未遂 - chūshi misui).

Article 43 of the Japanese Penal Code provides a powerful incentive for criminals to have second thoughts. It states that if a person commences a crime but voluntarily abandons it or prevents its completion, their punishment must be reduced or remitted entirely. This is a policy choice designed to encourage the prevention of harm, even after a crime is already in motion.

The central question before the Supreme Court was whether this significant legal benefit, which applies to a criminal attempt, could also be extended to a criminal preparation.

The Supreme Court's Decisive Answer: No

The Supreme Court definitively rejected the defendant's plea. In a categorical statement that would echo through decades of jurisprudence, the Court declared:

"...there is no room to allow for the concept of a discontinued attempt in the crime of preparation."

The Court's ruling was not limited to the specific facts of the case or even to the crime of robbery preparation. It was a broad declaration that the doctrine of voluntary abandonment does not apply to the entire category of preparatory offenses.

The Logic Behind the Ruling: The "Completed Crime" Theory

While the 1954 decision itself did not elaborate extensively on its reasoning, subsequent court decisions and legal analysis have clarified the formal logic behind this seemingly harsh rule. The rationale rests on how Japanese law classifies the crime of preparation.

In the eyes of the law, a "crime of preparation" like robbery preparation is not an "attempt" to commit robbery. It is a separate, independent, and self-contained offense.

The crime is legally "completed" (既遂 - kisui) the moment the preparatory acts are finished with the requisite criminal intent. In this case, the crime of robbery preparation was perfected the instant the group, armed with weapons and a common purpose, arrived at the scene.

From this perspective, the Court's conclusion is a matter of pure logic. The doctrine of "discontinued attempt" (chūshi misui) can only apply to a crime that is still in the "attempt" phase (i.e., legally incomplete). It cannot, by definition, apply to a crime that is already legally "completed" (kisui). The defendant did not abandon an attempted preparation; she fully completed the crime of preparation and then simply chose not to commit a second and different crime—the robbery itself.

The Punishment Paradox and the Academic Debate

This formal logic, while internally consistent, creates the "punishment paradox" that has been the subject of intense academic debate ever since. The result is that:

- A perpetrator who begins an attempt (e.g., breaks down the door) but then voluntarily stops receives a mandatory sentence reduction.

- A perpetrator who prepares for the crime (e.g., arrives at the door with weapons) but voluntarily stops receives no mandatory sentence reduction for the crime of preparation.

Critics argue that this creates a perverse incentive. The law more strongly encourages a criminal to stop later in the process, after a more direct danger has already been created, than it does to stop earlier. From a public policy standpoint of preventing harm, this seems backward. Many scholars have argued that the rule for voluntary abandonment should be "analogously applied" to preparatory offenses to resolve this imbalance and encourage criminals to desist at the earliest possible moment.

Conclusion

The 1954 Supreme Court decision remains a landmark ruling that draws a bright, formalistic line between the legal concepts of preparation and attempt. By classifying preparatory offenses as independent, "completed" crimes, the Court logically concluded that the doctrine of voluntary abandonment could not apply. While this creates a punishment paradox that has troubled legal scholars for decades, the Court's clear and unwavering logic has stood the test of time and remains the definitive law in Japan. The case serves as a powerful illustration of how formal legal reasoning can sometimes produce outcomes that appear counter-intuitive from a purely practical or policy-oriented perspective, highlighting the ongoing tension between doctrinal consistency and a law's real-world incentives.