The Obligation to Work Overtime in Japan: Analyzing a Landmark Supreme Court Decision (November 28, 1991)

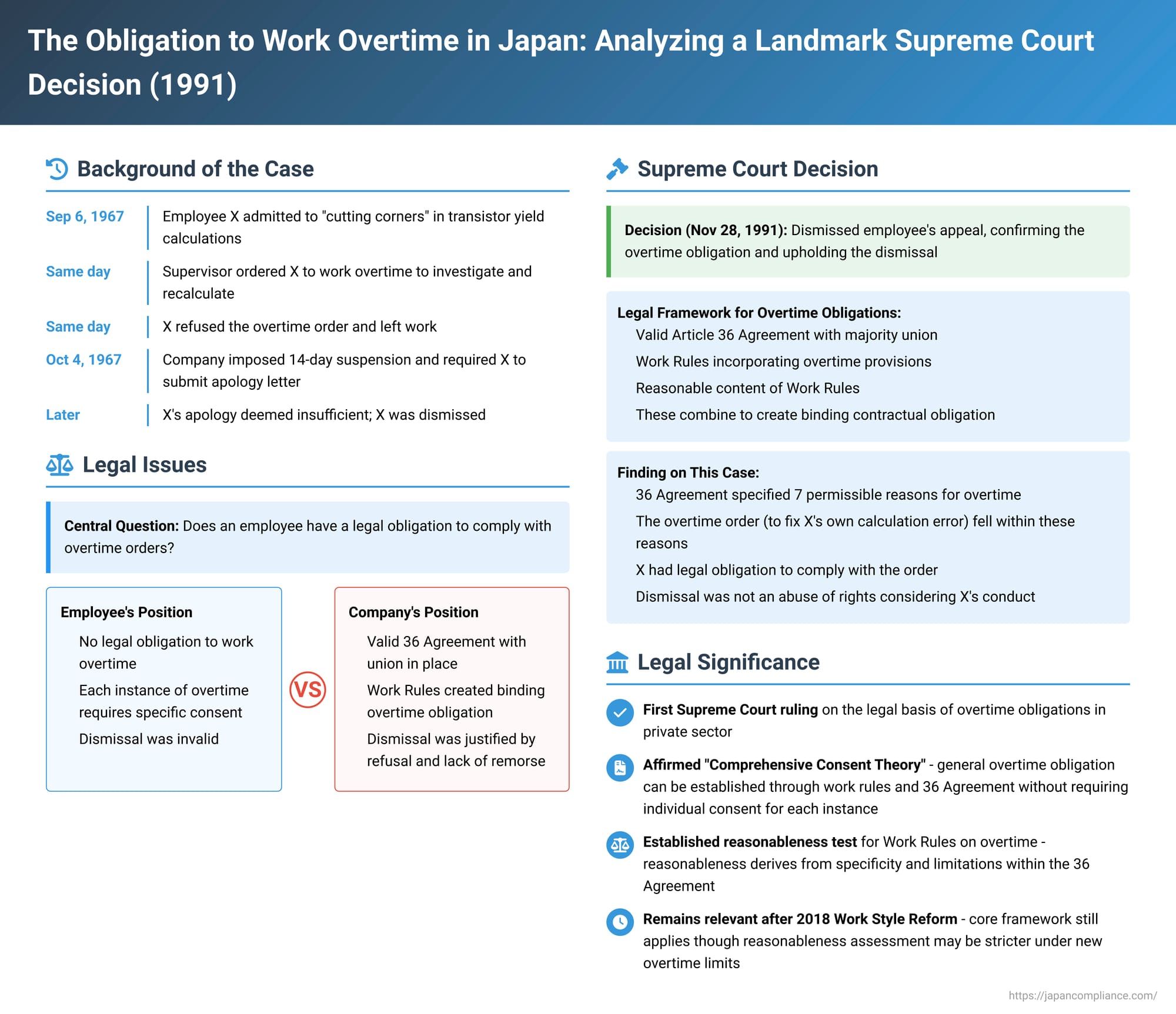

On November 28, 1991, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a pivotal judgment in a case concerning an employee's obligation to perform overtime work and the validity of a dismissal for refusing such work. This case, often referred to by commentators as the "Hitachi Manufacturing Musashi Plant Case," provides fundamental principles for understanding when Japanese employers can require overtime.

The Factual Background: An Overtime Order and Its Aftermath

The case involved Employee X, who worked at the M Plant of Company Y, a manufacturing concern. X was engaged in tasks related to improving the quality and yield of transistors.

The events leading to the dispute unfolded as follows:

- The Error and the Order: On September 6, 1967, X's supervisor, A, discovered that actual production yields were lower than X's calculated estimates. Upon questioning, X admitted to having "cut corners" or performed substandard work (手抜き作業 - tenuki sagyō) in his calculations. Consequently, Supervisor A ordered X to work overtime that same day to investigate the cause of the discrepancy and recalculate the yield estimates.

- Refusal and Departure: Employee X refused this overtime order and left work for the day.

- Work Rules and the 36 Agreement:

- Company Y's M Plant had Work Rules which stipulated that the standard eight-hour workday could be extended if operational needs required it, based on an agreement with the B Union. B Union was the labor union representing a majority of employees at the M Plant.

- A formal written agreement under Article 36 of the Labor Standards Act (an "Article 36 Agreement" or "36 Agreement") was in place between Company Y (M Plant) and B Union. This agreement, properly filed with the local Labor Standards Inspection Office, permitted overtime for several specified reasons, including:

- Risk of serious disruption if delivery deadlines were not met.

- Urgent tasks related to payroll, inventory, audits, or payments.

- Piping, wiring, or similar work difficult to perform during regular hours.

- Urgent needs for moving, installing, or repairing equipment.

- Necessity to achieve production targets.

- When unavoidable due to the nature of the work.

- Other reasons analogous to the preceding points.

- The 36 Agreement generally capped such overtime at 40 hours per month, though provisions existed for emergency extensions if agreed upon in advance.

- Disciplinary Actions:

- Following the overtime refusal, Company Y imposed a 14-day suspension on X on October 4, 1967, and also required him to submit a formal letter of apology or explanation (始末書 - shimatsusho).

- X submitted a letter, but Company Y rejected it as not demonstrating sufficient remorse or reflection. X continued to maintain that he had no obligation to follow the overtime order.

- Subsequently, Company Y dismissed X. The grounds for dismissal were X's perceived lack of remorse and repentance, viewed in conjunction with his past disciplinary record, under a Work Rule provision allowing for dismissal when an employee "despite repeated disciplinary actions or warnings, shows no prospect of repentance".

- Legal Challenge: Employee X challenged the dismissal's validity, seeking confirmation of his employment status. The first instance court ruled in X's favor, finding no overtime obligation. However, the Tokyo High Court (the appellate court in this instance) overturned this, affirming the overtime obligation and the validity of the dismissal. Employee X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed Employee X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that the dismissal was valid. The Court's reasoning laid out a clear framework for determining an employee's obligation to work overtime.

I. The Legal Basis for an Overtime Obligation

The Court established that an employee's obligation to work overtime can arise if specific conditions are met:

- If an employer has concluded a written Article 36 Agreement with a majority union (or an employee representative if no such union exists) permitting the extension of working hours beyond the limits set by Article 32 of the Labor Standards Act, and this agreement has been duly filed with the competent Labor Standards Inspection Office Director-General.

- And, if the employer's Work Rules, applicable to the specific workplace, contain provisions stating that, within the scope defined by that Article 36 Agreement, employees can be required to work beyond their contractually stipulated hours for certain defined operational reasons.

- Then, provided that the content of these Work Rule provisions is reasonable, these provisions become an integral part of the specific employment contract between the employer and the employee.

- Consequently, employees subject to such Work Rules are obligated to perform overtime work as stipulated therein.

In articulating this, the Supreme Court referenced its earlier landmark rulings on the binding nature of reasonable work rules. This anchors the overtime obligation in the established legal principle that work rules, when reasonable, can modify individual employment contracts.

II. Assessing the "Reasonableness" of the Work Rule Provisions

Applying this framework to the present case, the Supreme Court found Company Y's Work Rule provisions regarding overtime to be reasonable:

- The concrete details of overtime work at the M Plant were governed by the existing 36 Agreement.

- This 36 Agreement not only set limits on the amount of overtime but also required that any overtime order be justified by one of the seven specific reasons enumerated within it.

- The Court acknowledged that some of these reasons (specifically items [5] "necessity to achieve production targets," [6] "unavoidable due to the nature of the work," and [7] "other similar reasons") were somewhat general and broad in their wording.

- However, the Court reasoned that the very purpose of Article 36 of the LSA contemplates the need for enterprises to flexibly adjust production plans to meet supply and demand dynamics.

- Considering the nature of Company Y's business at the M Plant, the types of duties performed by employees like X, and the typical workflow, the Court concluded that these more general reasons (items [5] through [7]) did not lack appropriateness in this context.

- Therefore, because the Work Rules incorporated these conditions from a valid and specific 36 Agreement, the Work Rule provisions themselves were deemed reasonable.

III. Application to Supervisor A's Overtime Order

The Court then determined that Supervisor A's specific order to Employee X fell within the permissible scope:

- Company Y had the authority to order X to work overtime if one of the conditions stipulated in the 36 Agreement was present.

- The overtime order issued by Supervisor A—requiring X to investigate the cause of the reduced transistor yield (a direct consequence of X's admitted corner-cutting) and to redo the yield estimations—was found to correspond to the situations described in items [5] through [7] of the 36 Agreement.

- As such, the Court concluded that Employee X had incurred a legally binding obligation to perform the overtime work as instructed.

IV. Upholding the Dismissal

Finally, the Supreme Court addressed the validity of X's dismissal:

- It highlighted that the overtime order was specifically aimed at rectifying and completing work that was deficient due to X's own admitted substandard performance.

- Considering this and all other facts established by the High Court (including the subsequent refusal to submit a satisfactory letter of apology and X's uncooperative attitude), the Supreme Court held that Company Y's decision to dismiss Employee X for failing to comply with the legitimate overtime order did not constitute an abuse of rights.

Deeper Insights and Contextual Understanding

This Supreme Court judgment is highly significant as it was the first time the Court directly addressed the basis of overtime obligations for employees in the private sector in Japan.

The "Comprehensive Consent" Principle

The ruling clearly aligns with the "comprehensive consent" theory (包括的同意説 - hōkatsuteki dōi setsu) regarding overtime obligations. This theory posits that an employee's general obligation to work overtime can be established through provisions in their employment contract, work rules, or a collective bargaining agreement, provided a valid Article 36 Agreement is also in place. This contrasts with the "individual consent" theory (個別的同意説 - kobetsuteki dōi setsu), which would require specific employee consent for each instance of overtime. The Supreme Court had previously indicated a similar stance for non-operational public sector employees, and this case firmly extended the comprehensive consent principle to the private sector based on reasonable work rules.

It's noteworthy that Justice Mimura, in a supplementary opinion to the main judgment, also discussed how a collective bargaining agreement itself, in conjunction with a 36 Agreement, could directly form the basis of an overtime obligation for union members covered by that collective agreement.

The Role and Nature of Article 36 Agreements

The Labor Standards Act generally prohibits employers from making employees work beyond statutory maximum hours. An Article 36 Agreement serves as a legal exception:

- It exempts the employer from criminal penalties for exceeding statutory hours (a "penal effect").

- It makes it legally possible, under private law, to set overtime hours within the agreed scope.

- However, the 36 Agreement itself does not automatically create an individual employee's duty to work overtime. A separate contractual basis – typically found in the work rules or individual employment contract, as affirmed by this judgment – is necessary to establish this positive obligation on the employee.

The Critical Test of "Reasonableness" for Work Rules

The judgment underscores that for work rule provisions concerning overtime to be binding, they must be "reasonable".

- In this case, the reasonableness was largely derived from the fact that the Work Rules were linked to a 36 Agreement which itself specified limitations on overtime hours and listed the permissible reasons for such work.

- This implies that most work rules based on a legally compliant 36 Agreement (which, by law, must detail overtime hours and the reasons for it) would likely be found reasonable.

Considerations in the Modern Labor Law Landscape (Post-2018 Reforms)

While this judgment predates the significant 2018 amendments to the Labor Standards Act (which introduced stricter regulations on overtime, including absolute caps), the commentary suggests that the core framework established by the Supreme Court (Point I above) remains influential. However, the assessment of "reasonableness" (Point II) could be affected by these later reforms:

- Specificity of Reasons: For 36 Agreements incorporating "special clauses" (allowing overtime beyond the usual monthly/annual limits in exceptional circumstances), the 2018 reforms and subsequent guidelines demand greater specificity in the reasons for such extended overtime. The somewhat general reasons (items [5]-[7]) accepted in this 1991 case might now be scrutinized more strictly and potentially deemed insufficiently specific if used in a special clause context, possibly impacting a finding of reasonableness.

- Adherence to Limits: Modern LSA (post-2018) sets upper limits on overtime hours, even with a 36 Agreement. Any 36 Agreement purporting to allow overtime beyond these statutory caps would be invalid, and work rules relying on such an invalid agreement could not create a binding overtime obligation.

- Necessity and Proportionality: Current guidelines emphasize that overtime should be kept to the "minimum necessary". The assessment of reasonableness for work rules based on regular 36 Agreements (not exceeding general limits) would also consider whether the agreed overtime hours are within what is "normally foreseeable" given the workplace's typical業務量 (work volume) and overtime trends.

Limits to Enforcing Overtime Obligations

Even when a general obligation to work overtime is established under the comprehensive consent theory, there are still limits:

- Operational Necessity: The employer must have a genuine, substantive operational need for the overtime, corresponding to one of the valid reasons in the 36 Agreement. While the Supreme Court in this specific case appeared to accept the employer's stated reason without deep probing, contemporary analysis suggests that, especially after the 2018 reforms, the assessment of "operational necessity" or "reason for overtime" should be applied with a degree of rigor.

- Abuse of Rights: An overtime order, even if generally permissible, could be deemed an abuse of the employer's rights under certain circumstances (a principle now reflected in Article 3, Paragraph 5 of the Labor Contract Act). This might occur if, for example, an employee has compelling, unavoidable personal reasons for not being able to perform the overtime, or if a balancing of the employer's operational needs against the detriment to the employee shows the order to be excessively harsh.

Nuances of the Disciplinary Action in this Specific Case

The commentary points out that Employee X's dismissal was not solely for the act of refusing overtime. It was compounded by his subsequent defiant attitude, his failure to submit what the company considered an acceptable letter of apology, and his past disciplinary history. This raises distinct legal questions, such as the permissibility of disciplinary action for refusing to submit a letter of apology in a particular manner, and whether the dismissal could be seen as a form of "double jeopardy" if it disproportionately punished the initial overtime refusal. However, the Supreme Court, focusing on the totality of X's conduct post-refusal, found the dismissal not to be an abuse of rights.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1991 judgment in the "Manufacturing Company Y M Plant Case" remains a cornerstone in Japanese labor law concerning overtime. It firmly establishes that a combination of a valid Article 36 Agreement and reasonable, corresponding provisions in the company's Work Rules can create a binding obligation for employees to perform overtime work. The concept of "reasonableness" is key, often tied to the specificity and limitations within the 36 Agreement itself. While subsequent legal reforms have added more layers of protection for workers regarding overtime hours and reasons, the fundamental principles laid out in this decision continue to shape the understanding of overtime duties in Japan.