The Moving Target: Challenging Tax Assessments When the Taxman Issues New Ones Mid-Lawsuit (Japan's Makarazuya Case)

Date of Judgment: September 19, 1967

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Reassessment Disposition, etc. (昭和39年(行ツ)第52号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

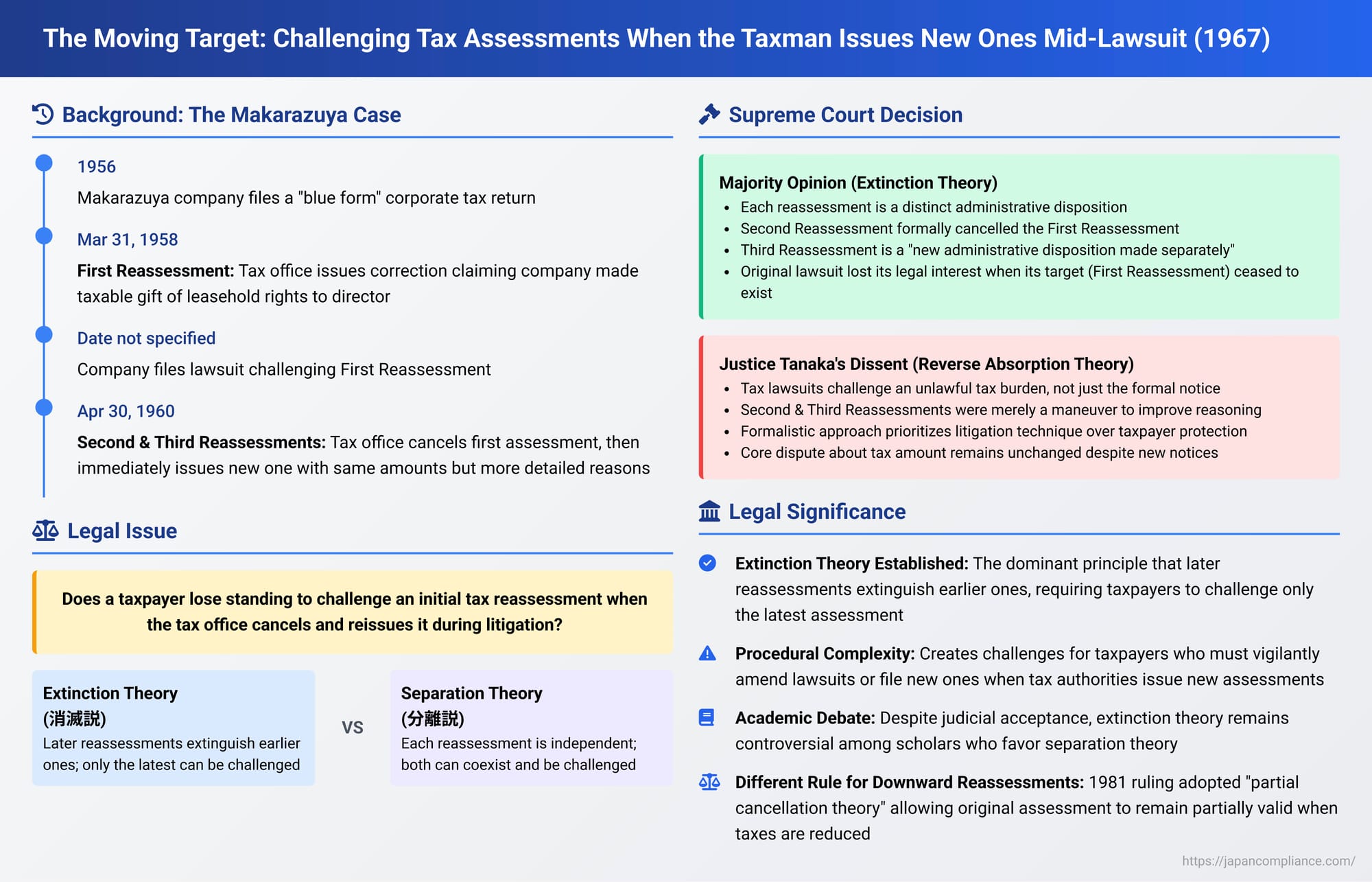

In a significant judgment on September 19, 1967, commonly known as the "Makarazuya case," the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a critical procedural issue in tax litigation: what happens to a taxpayer's lawsuit challenging an initial tax reassessment when the tax authorities issue further reassessments concerning the same tax liability while the original lawsuit is still pending? The Court's decision, which has been influential (though also debated), largely established the "extinction theory," holding that a subsequent reassessment can extinguish the legal interest in challenging the earlier one.

The Tax Dispute and the Shifting Sands of Reassessments

The plaintiff, X (Kabushiki Kaisha Makarazuya Yohinten, a clothing store in Kobe), was a corporation approved to file "blue form" tax returns, a system offering certain tax advantages in exchange for maintaining detailed accounting records. For its fiscal year Showa 31 (approximately 1956), X filed a corporate tax return declaring a tax liability of ¥1,066,767.

Subsequently, on March 31, 1958, the head of the Kobe Tax Office, Y, issued a corrective reassessment (hereinafter, "First Reassessment") against X. The primary reason for this reassessment was the tax office's determination that X had effectively made a taxable gift of leasehold rights to its representative director by selling the company's store premises to him at a price significantly below fair market value. This alleged gift was treated as a non-deductible donation for corporate tax purposes, leading to an increase in X's taxable income to ¥2,423,100. The reassessment notice stated "Donation ¥1,275,203" as the grounds.

X contested this First Reassessment, first through an administrative appeal to the Osaka Regional Tax Bureau Director, which was rejected. The Director upheld the tax office's view that X had transferred the building at an unduly low price, thereby gifting the economic difference to the director. X then filed a lawsuit in court seeking the cancellation of the First Reassessment. In its lawsuit, X argued that no gift of leasehold rights had actually occurred, that the amount calculated by the tax office was incorrect (claiming the disputed amount should be ¥1,373,560, if anything), and, crucially, that the reasons provided in the First Reassessment notice were insufficient and lacked specific factual basis.

While this lawsuit against the First Reassessment was pending, on April 30, 1960, the tax office (Y) took further action. It issued two more reassessment notices to X, both sent in the same envelope:

- Second Reassessment: This notice effectively cancelled the First Reassessment by reducing X's taxable income for the Showa 31 fiscal year back to the amount X had originally declared in its initial tax return.

- Third Reassessment: Issued immediately alongside the Second Reassessment, this notice then reassessed X's income and tax liability back to the same monetary amounts as the First Reassessment. However, this Third Reassessment notice provided more detailed reasons and justifications for the tax office's position regarding the alleged donation.

Following these actions, the tax office (Y) argued in court that X's original lawsuit, which specifically sought the cancellation of the First Reassessment, had lost its legal basis or "legal interest to sue" (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki, akin to standing). Y contended that since the First Reassessment had been formally cancelled and superseded by the Second Reassessment, there was no longer an existing administrative disposition for X's lawsuit to target. The lower courts (Kobe District Court and Osaka High Court) agreed with this argument and dismissed X's lawsuit without ruling on the substantive merits of the tax dispute. X then appealed this procedural dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Procedural Quagmire: Which Assessment to Sue?

The core legal question before the Supreme Court was a procedural one: When a tax authority issues an initial reassessment, and the taxpayer initiates a lawsuit to cancel it, what is the legal effect on that pending lawsuit if the tax authority subsequently issues one or more further reassessments that alter or replace the initial one? Specifically, does the taxpayer lose their "legal interest to sue" with respect to the original reassessment if it is formally cancelled by a subsequent administrative act, even if that cancellation is immediately followed by a new reassessment that substantially reinstates the original tax liability?

This issue involves competing legal theories on the relationship between successive tax assessments:

- Extinction Theory (消滅説 - shōmetsu setsu) or Absorption Theory (吸収説 - kyūshū setsu): This theory posits that a later reassessment (particularly an upward one, or one that replaces the earlier one) extinguishes or absorbs the earlier assessment, making the latest assessment the sole object of any legal challenge.

- Separation Theory (分離説 - bunri setsu) or Coexistence Theory (併存説 - heizon setsu): This view holds that each reassessment is an independent administrative act, and both the original and subsequent reassessments can coexist and be independently challenged, at least concerning the portions they respectively assert or modify.

- Reverse Absorption Theory (逆吸収説 - gyaku kyūshū setsu) or Investment Theory (投入説 - tōnyū setsu): Championed by the dissenting justice in this case, this theory suggests that an initial lawsuit challenging a reassessment should be understood as encompassing a challenge to the underlying unlawful tax burden, and thus later reassessments related to the same core dispute are effectively drawn into the scope of the original lawsuit.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Original Lawsuit Loses Standing (Extinction Theory Affirmed)

The Supreme Court's majority opinion dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' view that the lawsuit specifically targeting the First Reassessment had lost its legal interest and was correctly dismissed.

The majority reasoned as follows:

- It acknowledged the peculiar nature of the tax office's actions: the Second Reassessment (cancelling the first) appeared to be merely a "preliminary procedure" (前提手続 - zentei tetsuzuki) to enable the Third Reassessment. Furthermore, the Third Reassessment, in substance, seemed to be little more than a restatement of the First Reassessment with the addition of more detailed reasons; the majority even conceded that "the validity of such actions is not without question."

- However, the majority emphasized that, formally, each of these actions (the Second and Third Reassessments) constituted an "independent administrative disposition" (各々独立の行政処分であることはいうまでもなく - ono ono dokuritsu no gyōsei shobun de aru koto wa iu made mo naku).

- Since X's lawsuit specifically sought the cancellation of only the First Reassessment, and this First Reassessment had been formally cancelled by the Second Reassessment (which X had not specifically challenged in the current proceedings), the legal object of X's lawsuit had ceased to exist.

- The Third Reassessment, according to the majority, must be construed as a "new administrative disposition made separately from the First Reassessment" (第一次更正処分とは別個になされた新たな行政処分であると解さざるを得ない - dai-ichiji kōsei shobun to wa bekko ni nasareta arata na gyōsei shobun de aru to kaisazaru o enai).

- Therefore, the lawsuit limited to seeking the cancellation of the (now defunct) First Reassessment had, from the moment the Second Reassessment was issued, lost its legal interest. The lower courts' judgment to this effect was deemed correct.

Justice Jiro Tanaka's Dissenting Opinion:

Justice Tanaka offered a strong dissent, arguing that the majority's highly formalistic approach prioritized litigation technique over substantive justice and the practicalities of taxpayer protection.

- He contended that a lawsuit to cancel a tax reassessment is, in essence, a claim by the taxpayer that they have been subjected to an unlawful tax burden exceeding their correct liability. The specific reassessment notice is merely the formal "peg" for this substantive challenge.

- If subsequent reassessments issued by the tax office during the litigation still impose what the taxpayer alleges to be an excessive tax, the original lawsuit challenging this unlawful state of affairs should not be so easily dismissed. The taxpayer's core complaint about the amount of tax due remains.

- Justice Tanaka viewed the Second and Third Reassessments in this particular case not as genuinely new and independent assessments based on new findings, but as a singular, combined maneuver by the tax office. The tax office, recognizing the potential defect in the reasoning of the First Reassessment (a point X was litigating), used the Second Reassessment to formally wipe the slate clean and the Third Reassessment to immediately reinstate the same tax amount but with purportedly improved reasoning.

- He argued that the Second and Third Reassessments were, in substance, merely a measure to supplement the reasons for the First Reassessment. To treat them as entirely separate and new dispositions, requiring the taxpayer to constantly amend their lawsuit or file new ones, would be overly burdensome and could effectively deny taxpayers a meaningful opportunity for judicial review. The focus should be on the substance of the dispute, which remained the same.

- He feared that allowing tax authorities to freely issue such successive reassessments, and thereby extinguish pending lawsuits unless the taxpayer navigates complex procedural amendments, would put taxpayers at a severe disadvantage and undermine the role of judicial review as a remedy.

Analysis and Implications: The Dominance of the "Extinction Theory"

The Makarazuya case is a leading precedent in Japanese tax litigation, generally understood to affirm the "extinction theory" (消滅説 - shōmetsu setsu), also known as the absorption theory. This theory holds that when an initial tax assessment or reassessment is followed by a further reassessment (particularly an upward one, or one that replaces the earlier one), the initial assessment is legally extinguished or absorbed into the later one. Consequently, a lawsuit targeting only the initial, superseded assessment loses its legal interest.

- Practical Challenges for Taxpayers: This doctrine, while offering a clear rule that the latest assessment is the one to be challenged, can create procedural complexities and potential pitfalls for taxpayers. If a tax authority issues a new reassessment while a lawsuit concerning a prior one is pending, the taxpayer must be vigilant and promptly amend their existing lawsuit or file a new one to target the latest disposition. Failure to do so can lead to their case being dismissed for lack of a proper object, as happened to Makarazuya.

- Debate and Academic Criticism: The PDF commentary provided with the case materials highlights that the extinction theory, while dominant in case law, has faced considerable academic criticism. Many scholars favor the "separation theory" (bunri setsu), which argues that each reassessment should be treated as an independent act, and the original assessment should remain a valid subject of litigation regarding the tax amount it initially imposed. This view often draws support from provisions in the General Act of National Taxes that seem to imply earlier tax liabilities retain a degree of independent existence even after subsequent reassessments. Critics of the extinction theory argue it can be unfair to taxpayers, potentially allowing tax authorities to "cure" defects in earlier assessments by simply reissuing them, thereby forcing taxpayers to restart the often lengthy and costly appeal process.

- Distinction for Downward Reassessments: It is important to note that the Supreme Court later adopted a different approach for downward reassessments. In a judgment from Showa 56 (1981) (April 24, Minshu Vol. 35, No. 3, p. 672), the Court held that a downward reassessment only affects the reduced portion of the tax, and the taxpayer can continue to challenge the remaining part of the original assessment. This "partial cancellation theory" (ichibu torikeshi setsu) creates a somewhat inconsistent treatment between upward/replacing reassessments (where the original is extinguished) and downward reassessments (where the original partially survives).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1967 decision in the Makarazuya case remains a significant, albeit debated, landmark in Japanese tax procedural law. It established the "extinction theory" as the prevailing judicial view regarding the effect of subsequent tax reassessments on pending litigation challenging earlier ones: generally, a later reassessment supersedes and extinguishes the prior one, requiring the taxpayer to focus their legal challenge on the latest administrative disposition. While this approach aims to provide clarity on the proper object of litigation, it also necessitates careful procedural maneuvering by taxpayers to ensure their substantive claims are not dismissed on procedural grounds. The strong dissenting opinion in the case, along with ongoing academic discussion, highlights the inherent complexities in balancing administrative finality, efficiency, and effective judicial remedies for taxpayers in the face of evolving tax assessments.