The Motive of a Disloyal Executive: A Japanese Ruling on the Intent Requirement for Breach of Trust

When a corporate executive makes a disastrously risky decision that harms their company while benefiting a third party, what separates a poor business judgment from a criminal act? If the executive claims their ultimate goal was to help their own company, does this "good" motive shield them from criminal liability for breach of trust?

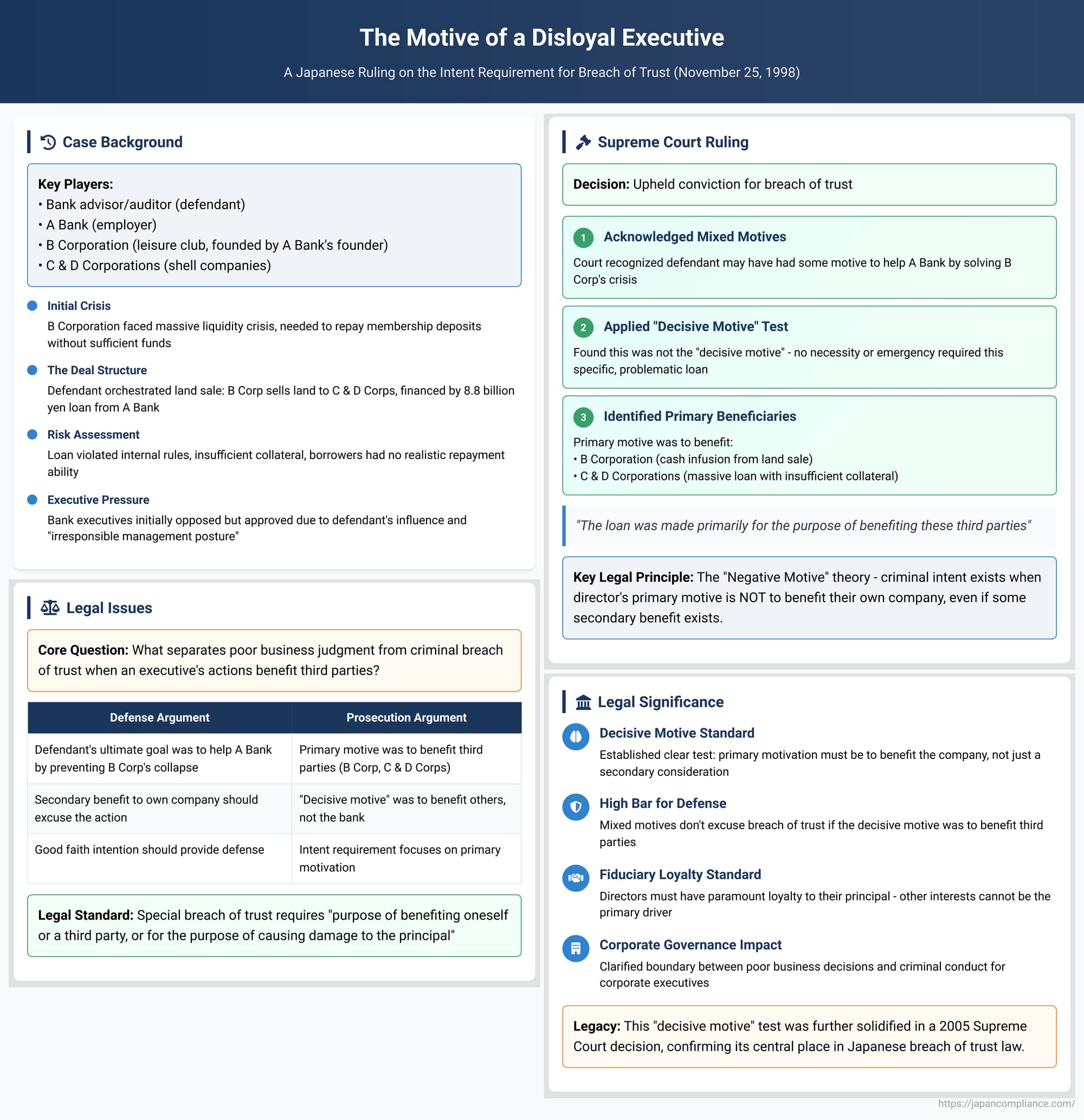

This question—which probes the subjective intent of a corporate fiduciary—was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on November 25, 1998. The case involved a powerful bank advisor who orchestrated a massive, high-risk loan to a struggling, related company. The Court's ruling clarified the crucial subjective element of the crime of breach of trust: the "intent to benefit oneself or a third party, or to harm the principal." It established that a secondary or potential benefit to one's own company is not enough to excuse a disloyal act undertaken primarily for the benefit of others.

The Legal Framework: The Subjective Element of Breach of Trust

The crime of "special breach of trust" (tokubetsu hainin-zai), which applies specifically to corporate directors and other fiduciaries, is defined in Japan's Companies Act. The crime requires that a director, acting contrary to their duties, causes financial damage to the company. However, unlike a simple act of negligence, it requires a specific criminal state of mind: the act must be done for the "purpose of benefiting oneself or a third party, or for the purpose of causing damage to the principal" (tori-kagay-mokuteki).

This subjective element is crucial. It narrows the scope of the crime to acts of genuine disloyalty, distinguishing it from mere incompetence or honest mistakes. The central legal debate has long been about how to define this intent. Is it enough that the director simply knew their actions would benefit a third party? Or must it be their primary, driving motivation? This 1998 decision provided a clear answer.

The Facts: The Bank, The Club, and The Risky Loan

The case involved a web of close and ultimately toxic relationships between A Bank and a members-only leisure club company, B Corporation. The defendant was a highly influential figure at A Bank, serving as both an auditor and its legal advisor. B Corporation, founded by A Bank's own founder, was in a precarious financial state. It faced a massive liquidity crisis, needing to repay membership deposits it did not have the funds for. A failure of B Corporation could have triggered a crisis of confidence in its closely linked partner, A Bank.

To raise cash, B Corporation sought to sell a large parcel of unused land. The defendant orchestrated a deal whereby two shell companies, C Corporation and D Corporation, would purchase the land. The entire purchase would be financed by a massive, 8.8 billion yen loan from A Bank.

The loan was, by any objective measure, extraordinarily risky and a clear violation of A Bank's internal lending rules. The collateral for the loan was grossly insufficient, and the borrowing companies had no realistic ability to repay the debt. The bank's own executives in charge of lending, including co-defendants X, Y, and Z, were all initially opposed to the deal, recognizing that it was almost certain to become a bad debt.

However, the defendant, as the architect of the deal and an influential figure at the bank, pushed the loan forward. The court found that the bank's executives, rather than exercising their own judgment, acted out of an "extremely easy and irresponsible management posture," ultimately approving the loan because the defendant said it was necessary. The court also analyzed the defendant's own motives, noting that while helping the bank was a potential goal, his more immediate motivations were to see a deal he had personally engineered come to fruition and to manage his relationships with the parties he had brought to the table.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The "Decisive Motive" Test

The Supreme Court upheld the defendant's conviction for breach of trust. Its ruling focused on a detailed analysis of the defendants' motives to determine if the "intent to benefit a third party" was present.

The Court acknowledged that the defendants may have had some motive to help their own institution, A Bank. By providing funds to B Corporation, they could solve B's immediate cash-flow problem and thus avert a crisis that might have harmed A Bank.

However, the Court found that this was not their "decisive motive." It noted that there was no "necessity or emergency" that required the bank to make this specific, highly problematic loan, as other, less risky options could have been explored.

Instead, the Court concluded that the primary motive was to benefit the other parties involved in the transaction:

- B Corporation gained the benefit of selling off an idle asset and receiving a massive cash infusion.

- C and D Corporations (the buyers) gained the benefit of receiving a huge loan with grossly insufficient collateral.

Because the loan was made "primarily for the purpose of benefiting" these third parties, the Court ruled that the "intent to benefit" requirement of the breach of trust statute was satisfied.

Analysis: The "Negative Motive" Theory in Practice

The Court's "decisive motive" test is a practical application of what is sometimes called the "Negative Motive" theory for breach of trust. Under this view, to establish the criminal intent, a prosecutor does not need to prove that the director had an overwhelming, active desire to enrich a third party.

Instead, it is sufficient to prove that the director's primary, "decisive" motive was not to benefit their own company. The absence of a primary, legitimate motive, when combined with actions that knowingly benefit a third party and harm the company, is enough to establish the disloyal intent required for the crime. This approach focuses on the why behind the breach of duty. If the main reason for the harmful act is not to serve the principal, the act is a criminal breach of trust.

This decision built upon a 1988 Supreme Court ruling that had hinted at this motive-based analysis, but the 1998 case was the first to use the word "motive" (dōki) explicitly and to frame the test as a comparison between the "decisive motive" and other, secondary intentions. This approach was further solidified in a 2005 Supreme Court decision, confirming its central place in the law.

Conclusion: A High Bar for Fiduciary Loyalty

The 1998 Supreme Court decision is a crucial ruling for Japanese corporate governance and criminal law. It provides a clear, if demanding, standard for assessing the subjective intent of directors in breach of trust cases.

The legacy of the ruling is its "decisive motive" test. To avoid criminal liability for a harmful transaction, a director's actions must be driven primarily and decisively by a good-faith intent to benefit their company. The existence of a secondary or "potential" benefit to the company will not excuse a disloyal act that is undertaken mainly for the benefit of the director themselves or, as in this case, a third party. The decision sends a clear message to corporate fiduciaries: their loyalty to their principal must be their paramount and decisive motivation. Any action that puts other interests first and causes foreseeable harm to the company risks crossing the line from a poor business decision into a serious crime.