The Mistake in Death: A 1923 Japanese Case That Defined a Century of Causation Law

Decision Date: April 30, 1923

Case Name: Murder

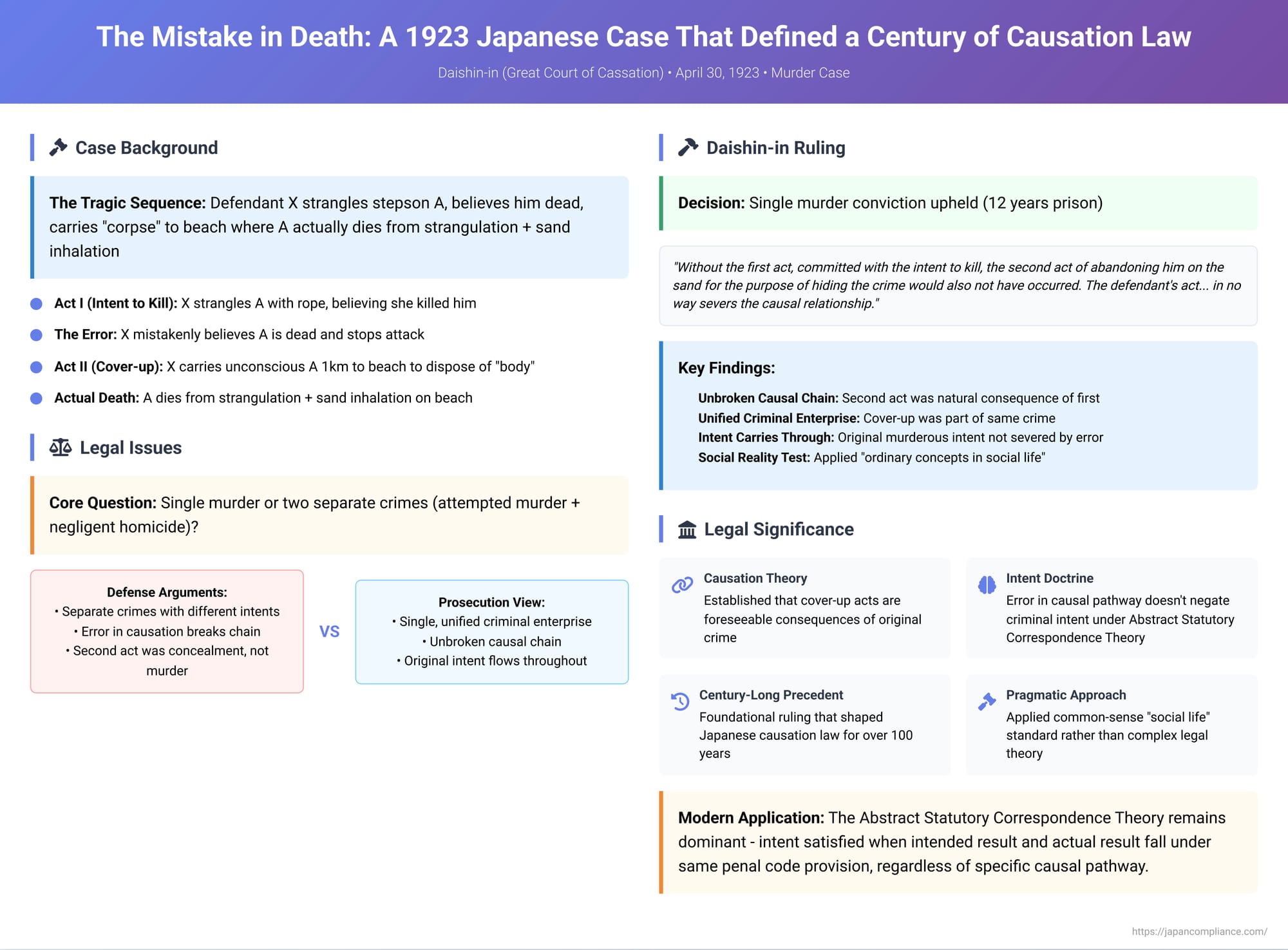

The annals of criminal law are filled with unusual facts, but few cases present a legal paradox as confounding as the one decided by Japan’s highest court, the Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), on April 30, 1923. The case involves a defendant who, after attempting to kill her stepson, mistakenly believes him to be dead. In her effort to dispose of what she thinks is a corpse, she inadvertently causes his actual death.

This scenario, often called the "later-than-expected realization of the crime," raises fundamental questions that strike at the heart of criminal liability. Is this a single, consummated murder, where the initial intent carries through the entire sequence of events? Or is it two separate acts: a failed murder attempt followed by a negligent killing? The 1923 ruling provided a foundational answer that has shaped Japanese legal thought on causation and intent for over a century, establishing a pragmatic and enduring principle for one of the most perplexing situations in criminal law.

The Facts: A Story of Despair and a Fatal Miscalculation

The facts of the case, as laid out in the court records, paint a tragic picture of domestic turmoil culminating in a bizarre and fatal sequence of events.

- The Relationship and Motive: The defendant, X, was involved in an illicit affair with her adult stepson, A. A had fallen ill, and his condition was creating a severe financial strain on the household. X, fearing both the continued financial burden and the potential discovery of their affair, decided that she had to kill him.

- Act I: The Intentional Attack: In the pre-dawn hours of a summer day, X acted on her decision. With clear intent to kill, she took a thin, 2.5-meter-long rope and strangled the sleeping A by the neck. She continued until he stopped moving.

- The Critical Error: At this point, X made a crucial mistake. Believing that A had already died from the strangulation, she ceased her attack.

- Act II: The Cover-Up: Operating under the false assumption that she was handling a corpse, X’s motive shifted to concealing her crime. To prevent the discovery of what she believed she had done, she carried A on her back, with the rope still around his neck, for approximately one kilometer to a nearby sandy beach. She left him on the sand and returned home.

- The Actual Cause of Death: However, A was not dead. Left unconscious on the beach, he died from a combination of the initial strangulation and the subsequent inhalation of sand into his lungs. The act of disposing of the "body" was what ultimately, and ironically, completed the act of killing.

X was charged with consummated murder, and the lower court found her guilty, sentencing her to 12 years in prison.

The Legal Battleground: The Defense's Challenge

The defendant's counsel appealed to the Daishin-in, mounting a sophisticated legal challenge that framed the core issue perfectly. The defense argued that finding X guilty of a single, consummated murder was a misapplication of the law for three key reasons:

- Separation of Crimes: The first act (strangling) was an attempted murder, as it did not result in death. The second act (leaving him on the beach) was, at most, a negligent homicide, as she lacked the intent to kill during this phase. Therefore, she should be convicted of two separate crimes, not one.

- Separation of Intent: A murderous act driven by intent cannot be legally combined with a subsequent act of concealment performed without homicidal intent to form a single, unified crime.

- Error in Causation: The defendant’s mistake about the causal process—believing death occurred from Act I when it actually resulted from Act II—was a fundamental error that should negate the intent required for a consummated murder conviction.

The Daishin-in's Landmark Ruling: An Unbroken Causal Chain

The Daishin-in rejected the defense's arguments and upheld the murder conviction. The court's reasoning was not based on complex legal theory but on a pragmatic, common-sense view of causation rooted in social reality.

The court reasoned as follows:

"Although it is true that without the second act of abandoning him on the sand, the inhalation of sand would not have occurred, it is also of course true that without the first act, committed with the intent to kill, the second act of abandoning him on the sand for the purpose of hiding the crime would also not have occurred. Viewing this through the lens of ordinary concepts in social life, it is proper to recognize a relationship of cause and effect between the defendant's act committed with the intent to kill and A's death. The defendant's act, which arose from the purpose of abandoning a corpse due to her mistaken belief, in no way severs the aforementioned causal relationship."

The court concluded that the entire sequence constituted the crime of murder under Article 199 of the Penal Code and was not a combination of attempted murder and negligent homicide. In essence, the court held that the second act was a direct and natural consequence of the first, and the initial intent to kill flowed through the entire chain of events.

A Deeper Analysis: The Two-Part Legal Problem

While the 1923 court’s conclusion was clear, modern legal analysis reveals that the case presents two distinct and complex legal questions that the court fused together in its practical reasoning.

- The Question of Legal Causation: Is there an objective causal link between the first act (the strangulation) and the final result (death), even with the defendant’s own second act (abandoning the body) intervening?

- The Question of Intent (Mens Rea): If causation is established, does the defendant's error about the specific causal pathway—the discrepancy between the intended cause of death and the actual cause of death—negate the legal intent required for a consummated murder?

Part I: Forging the Unbroken Chain of Causation

The first hurdle is establishing that the strangulation can be considered the legal cause of death. Modern legal theory largely supports the Daishin-in's conclusion on this point. The reasoning is that the second act is not an abnormal, unforeseeable, or independent event. Rather, it is a highly predictable consequence directly "induced" by the first criminal act. A person who has just committed what they believe to be a murder will naturally and foreseeably take steps to conceal the crime. The second act is part of the same criminal enterprise, driven by the need to cover up the first act.

Legal causation would likely be severed only in a scenario where the second act introduced a completely new and unrelated risk, especially if the defendant had a change of heart. For instance, if X had realized A was alive, repented, and tried to perform a rescue, but did so in a grossly negligent way that created a new danger (e.g., causing a fatal accident while rushing to a hospital), then a court might find the chain of causation broken. In such a case, a conviction for attempted murder (for Act I) and negligent homicide (for Act II) would be appropriate. But in the actual case, where the second act was a continuation of the criminal plan, the chain remains intact.

Part II: The Nature of Intent and the Irrelevance of Error

Once legal causation is established, the second question arises: does the mistake matter for the purposes of intent? The defendant intended to kill A by strangulation, but the actual death was caused by strangulation and sand inhalation. The actual causal process differed from the one she envisioned. Does this factual error absolve her of guilt for the completed crime?

The dominant legal theory in Japan, both then and now—the Abstract Statutory Correspondence Theory (chūshōteki hōtei fugōsetsu)—provides a clear answer: the error is legally irrelevant.

This theory holds that criminal intent is satisfied as long as the intended result and the actual result fall under the same provision of the penal code. X intended to kill "a person" (A), and "a person" (A) died as a direct causal result of her actions. The specific causal pathway or the precise mechanism of death is not considered an essential element of the crime of murder that must be specifically intended. The core elements—the intent to kill and the resulting death of a person—match. Therefore, under this theory, there is no room to negate the intent for the consummated crime. If the facts established a legally valid causal chain, the inquiry into intent ends there, and a conviction for murder is the only possible outcome.

While other theories exist, such as the Concrete Statutory Correspondence Theory (gutaiteki hōtei fugōsetsu), which demands a closer match between intent and result, even under this more stringent view, most scholars would argue that the specific causal process is not a "concrete fact" that would alter the identity of the crime. The crime is "the murder of A," and minor deviations in how that result is achieved do not change its fundamental nature.

The Enduring Legacy of the 1923 Ruling

The Daishin-in's 1923 decision in what is often called the "Sand Inhalation Case" has stood for a century as a pillar of Japanese criminal law. It pragmatically resolved a deeply complex legal issue by grounding its reasoning in the common-sense observation that a criminal's effort to conceal their crime is an integral part of the crime itself.

The ruling established the enduring principle that a defendant's initial intent to kill is not nullified simply because they misjudged the precise moment of death. As long as their subsequent actions are a natural and foreseeable continuation of the original criminal enterprise, the initial intent flows through the entire sequence, and the unbroken causal chain holds them responsible for the final, consummated crime.