The Meeting's Over, But the Duty Isn't: A Japanese Ruling on Obstructing a Public Official

Imagine a contentious public meeting that descends into chaos. The chairman, unable to proceed, pounds the gavel and declares a recess. The formal proceedings have stopped. If angry protestors then physically assault the chairman as he attempts to leave the room, can they be found guilty of "Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty"? Or did the chairman's official duty end the moment he declared the recess, making the subsequent attack a simple, albeit illegal, assault?

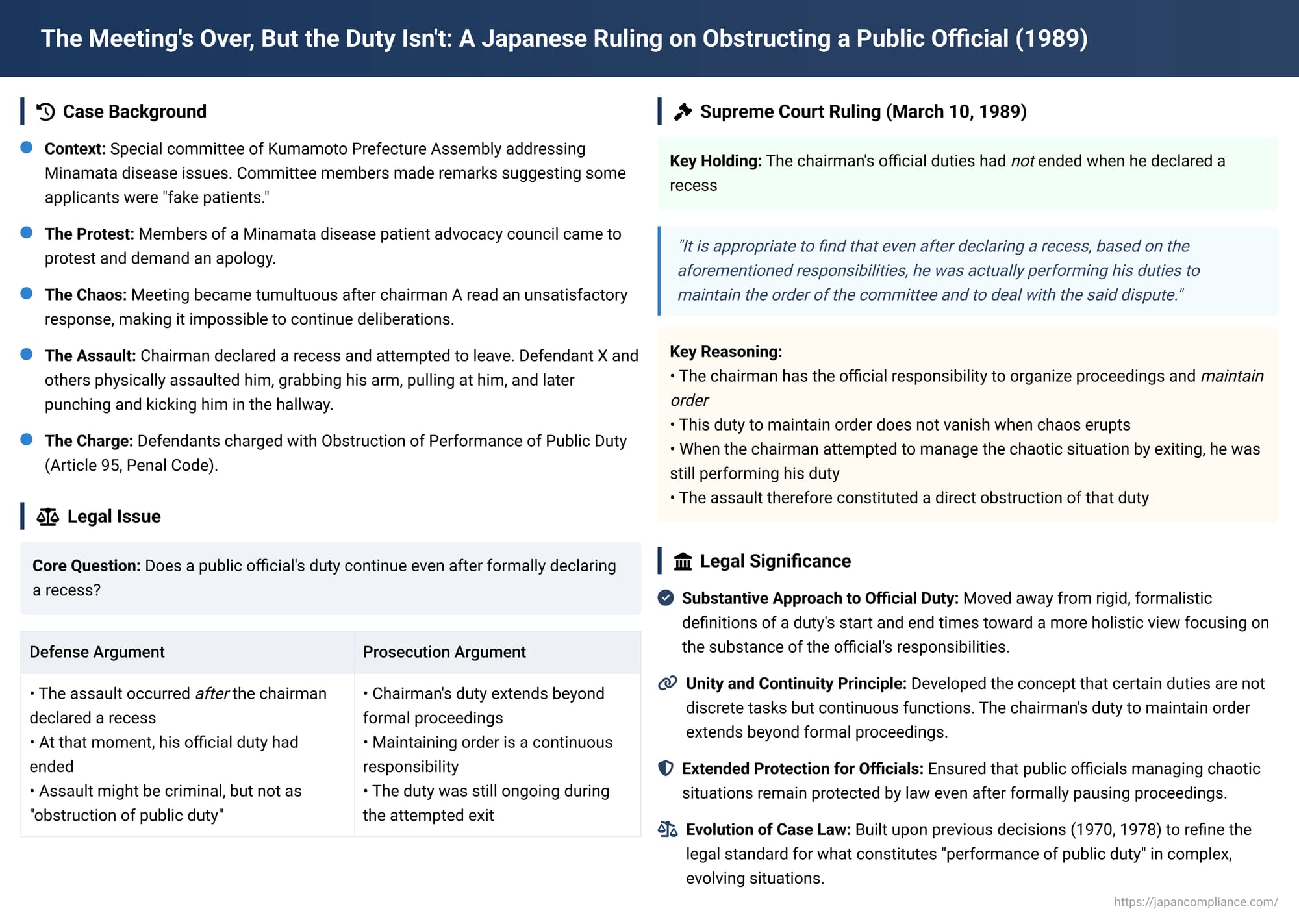

This question, which probes the precise temporal limits of a public official's duty, was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 10, 1989. The ruling, stemming from a violent confrontation at a prefectural assembly committee meeting, established that the law should look at the substance, not the mere form, of a public official's duty, and that in some circumstances, that duty continues even after the proceedings have been formally paused.

The Facts: Chaos in the Committee Room

The case arose from a highly emotional and politically charged situation in Kumamoto Prefecture.

- The Context: A special committee of the prefectural assembly on pollution countermeasures was addressing issues related to Minamata disease, a devastating neurological disease caused by industrial mercury poisoning. Members of the committee had reportedly made insensitive remarks, suggesting that some compensation applicants were "fake patients," which was then reported in the local press.

- The Protest: In response, members of a Minamata disease patient advocacy council and their supporters went to the prefectural assembly to protest and demand an apology.

- The Confrontation: The committee chairman, A, convened the committee and read an official response to the protestors' demands. The protestors deemed the response unsatisfactory and began to protest vociferously. The committee room descended into a chaotic and tumultuous state, making it impossible to continue the deliberations.

- The Assault: Seeing that the meeting could not proceed, Chairman A declared a recess and attempted to leave his seat. At that moment, Defendant X and three other protestors conspired to block his exit. They surrounded Chairman A, grabbed his right arm and side, and pulled at him. After he managed to exit the committee room, they continued the assault in the hallway, punching and kicking him.

The four protestors, including X, were charged with Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty for this assault.

The Legal Defense: "The Meeting Was Over"

The core of the defendants' legal argument was based on timing.

- They argued that the assault occurred after the chairman had officially declared a recess.

- At that moment, they contended, he was no longer "in the performance of his duties" but was simply a man trying to leave a room.

- Therefore, while they might be guilty of the crime of assault, they could not be guilty of the specific, more serious crime of obstructing a public duty under Article 95 of the Penal Code.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The Duty to Maintain Order Continues

The Supreme Court rejected this defense and upheld the convictions. The Court's crucial finding was that the chairman's official duties had not, in fact, ended when he declared the recess.

The Court reasoned:

- The chairman of a committee has the official responsibility (shokuseki) to organize the proceedings and, critically, to maintain order.

- When the committee room erupted into chaos, the chairman's duty to maintain order and deal with the dispute did not simply vanish.

- Therefore, the Court concluded, "it is appropriate to find that even after declaring a recess, based on the aforementioned responsibilities, he was actually performing his duties to maintain the order of the committee and to deal with the said dispute."

Because he was still performing his duty to manage the chaotic situation, the assault constituted a direct obstruction of that duty.

Analysis: A "Substantive" Approach to Official Duty

This 1989 decision is a key refinement of the legal standard for what it means to be "in the performance of" a public duty. It builds upon a line of cases that moved away from a rigid, formalistic definition of a duty's start and end times toward a more substantive, holistic view.

- The Evolution of the Standard: A 1970 Supreme Court decision had established that the obstructed duty must be "specific and individualized," which some lower courts interpreted very narrowly. However, a subsequent 1978 Supreme Court ruling introduced the concept of "unity and continuity" (ittaisei, keizokusei). This allowed courts to view certain duties not as a series of discrete, start-and-stop tasks, but as a single, continuous function. For example, the overall management of a public office was seen as a continuous duty, even if the director was interrupted while performing a specific task.

- This Case as a Refinement: The 1989 ruling is a clear application of this "unity and continuity" principle. It holds that a chairman's duty is not just to follow the items on the agenda, but to manage the entire situation that arises from the official proceedings. The duty to "maintain order" is a continuous responsibility that is activated by disorder and does not end until that disorder is resolved or the chairman has successfully disengaged from the situation.

- Not a Crime of "After the Fact": It is crucial to understand that the Court did not rule that assaulting an official "immediately after" their duty is complete constitutes this crime. Such a ruling is controversial, as the duty itself is over and arguably can no longer be obstructed. Instead, the Court cleverly and substantively re-characterized the facts, finding that the chairman's duty itself was still ongoing. Because of the chaos that erupted from the meeting, his responsibility to manage that chaos continued, even after he formally paused the agenda.

Conclusion

The 1989 Supreme Court decision provides a vital and pragmatic interpretation of what it means for a public official to be "in the performance of" their duties. It establishes that courts should look at the substantive reality of a situation, not just the formal declarations of a meeting's status. The ruling's key legacy is the principle that when a public official's responsibilities include maintaining order and managing proceedings, those duties continue as long as a state of disorder directly arising from those proceedings persists. An official attempting to manage or safely navigate such chaos is still acting in their official capacity and is protected by the law against violent obstruction. The decision thus ensures that the protection afforded to public service is not artificially terminated by the very chaos that seeks to disrupt it.