The Meaning of Instigation: A 2006 Supreme Court Ruling on Crystallizing Criminal Intent

Decision of the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan, November 21, 2006

(Case No. 2005 (A) No. 302: Case of Corporate Tax Law Violation and Instigation of Evidence Tampering)

Introduction

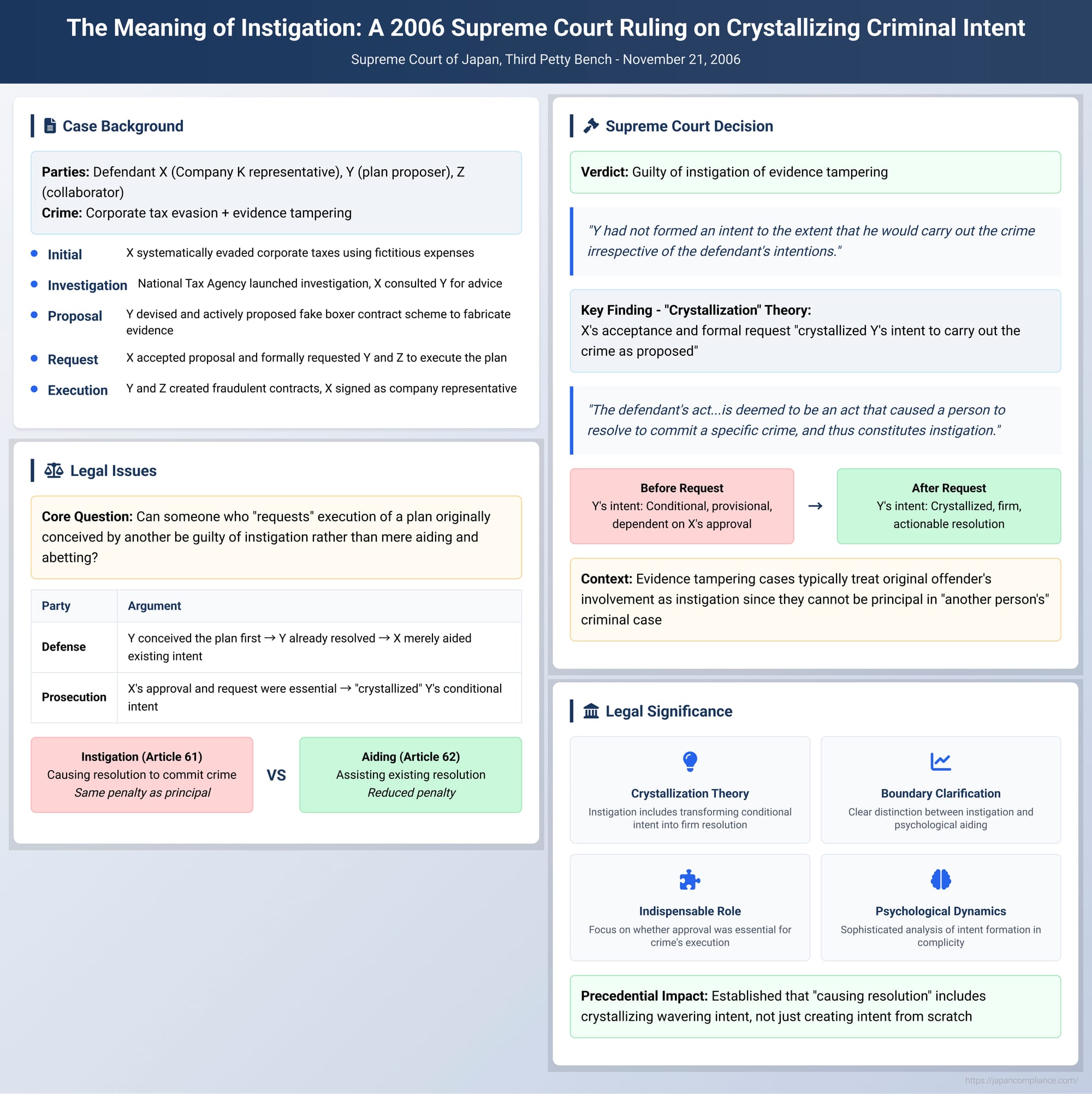

On November 21, 2006, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a pivotal decision clarifying the legal definition of criminal "instigation" (kyōsa). The case presented a nuanced scenario: can a person be guilty of instigating a crime when the individual they supposedly "instigated" was the one who originally conceived of and proposed the criminal plan? This ruling delves into the subtle psychological dynamics of complicity, examining the precise moment when a person's inclination to commit a crime transforms into a firm "resolution." By focusing on the act of "crystallizing" a previously uncertain intent, the Court refined the boundary between instigation—which carries a penalty equivalent to that of a principal offender—and the lesser offense of aiding and abetting.

Factual Background

The Tax Evasion and the Desperate Search for a Solution

The defendant, X, was the representative director of Company K, a firm that organized martial arts events. X had been systematically evading corporate taxes by reporting fictitious expenses. When the National Tax Agency launched an investigation, X, fearing arrest and punishment, sought advice from an acquaintance, Y.

The Proposal from the "Instigatee"

Y, upon being consulted, devised a sophisticated plan to fabricate evidence. He proposed creating a fake contract involving a famous foreign professional boxer who was supposedly scheduled to appear in one of Company K's events. The contract would include a clause for a massive penalty fee for non-performance. This fictitious penalty fee could then be booked as an off-the-books expense, thereby reducing Company K's taxable income for the relevant periods. Y actively and strongly recommended this course of action to X, arguing it was the only way to offset the large profits from specific fiscal years.

The Defendant's "Request" and the Execution of the Plan

X decided to accept Y's proposal. He then asked Y to explain the plan to another collaborator, Z. At a meeting of all three individuals, Y laid out the scheme for Z, who agreed to participate. Following this, X formally requested that Y and Z create the fraudulent contract documents.

Y and Z accepted the request and conspired to forge the contracts. They prepared the documents, which Z signed. The contracts were then presented to X, who signed them in his capacity as the representative of Company K, thereby completing the act of evidence fabrication.

A key factual finding by the courts was that while Y received a large sum of money from X, ostensibly as funds for this operation, there was no evidence to suggest that Y had the motivation or intention to carry out the evidence fabrication on his own if X had rejected the proposal or had not formally requested its execution.

The Legal Dispute: Instigation or Aiding?

The Charge and the Defendant's Defense

X was charged not only with corporate tax evasion but also with instigating Y and Z to tamper with evidence related to his criminal case.

X's defense team contested the instigation charge. They argued that Y, the supposed "instigatee," was the one who had conceived of and proposed the specific criminal act. Therefore, Y had already formed the intent to commit the crime before X's formal "request." X's action, they claimed, was merely a final go-ahead given to someone already resolved to commit the crime, which does not meet the legal requirement for instigation—namely, "causing another person to resolve to commit a crime."

The Core Legal Question: When is Criminal Intent "Resolved"?

Japanese law draws a critical distinction between two forms of complicity:

- Instigation (Article 61 of the Penal Code): Causing a person who has no intention to commit a crime to form a resolution to do so. The penalty is the same as for the principal offender.

- Aiding and Abetting (Article 62): Assisting a person who has already resolved to commit a crime. This often takes the form of "psychological aiding" if it involves merely encouraging or strengthening an existing resolve. The penalty is mandatorily reduced from that of the principal.

The case turned on this distinction. Was Y's criminal intent already at the level of a "resolution" before X's request, or was it still in a conditional or indeterminate state?

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' convictions, finding that X's actions did indeed constitute instigation. Its reasoning focused on the qualitative nature of Y's intent before and after X's request.

"Crystallizing" an Uncertain Intent

The Court acknowledged that Y was more than a mere consultant; he had devised and actively proposed the plan. However, it crucially found that "Y had not formed an intent to the extent that he would carry out the crime in this case irrespective of the defendant's [X's] intentions."

Y's plan was contingent upon X's approval and participation. Without X's signature on the contracts and his financial backing, the scheme was impossible to execute and offered no benefit to Y. Therefore, Y's intent prior to X's request was merely conditional or provisional.

The Defining Moment of Instigation

The Supreme Court identified X's acceptance of the proposal and his formal request for its execution as the pivotal act. This act transformed Y's fluid, conditional willingness into a concrete, actionable plan. In the Court's words:

"The defendant's act of accepting Y's proposal...and requesting the execution of the proposed operation crystallized Y's intent to carry out the crime as proposed."

Therefore, the Court concluded that X's conduct "is deemed to be an act that caused a person to resolve to commit a specific crime, and thus constitutes instigation."

Analysis and Implications

Redefining the "Resolution to Commit a Crime"

This decision offers a more sophisticated understanding of what it means to "cause a resolution." The Court did not require that the instigator generate a criminal intent from a complete vacuum. Instead, it established that instigation also includes the act of transforming an uncertain, conditional, or provisional intent into a firm and determined one. The instigator provides the final, essential element that "crystallizes" the criminal resolve.

The Boundary with Psychological Aiding

The ruling helps to clarify the line between instigation and psychological aiding. Had the facts shown that Y was determined to fabricate evidence by some means, with or without X's specific approval, then Y would have been deemed "already resolved." In that scenario, X's request would likely have been classified as mere psychological aiding, strengthening an existing intent. However, because Y's intent was entirely dependent on X's buy-in, X's approval became the decisive push that created the resolution.

The "Indispensable Role" Theory

Some legal theories ground the punishment for instigation in the "significant role" the instigator plays in the realization of the crime. From this perspective, X's approval and request were the "indispensable" conditions precedent for the crime's execution. His role was not peripheral but central, justifying his liability as an instigator, on par with a principal offender.

The Peculiarity of Evidence Tampering Cases

It is also important to note the specific context of evidence tampering in Japanese law. When a person (the original offender) takes part in concealing or fabricating evidence related to their own criminal case, they are typically not prosecuted as a co-principal of the evidence tampering. This is because the crime of evidence tampering (Article 104 of the Penal Code) is defined as tampering with evidence in "another person's" criminal case. Since the original offender cannot be a principal in this crime, Japanese case law has established a practice of treating their involvement as instigation. The charges against X in this case followed this established judicial tradition, which explains why he was prosecuted for instigation rather than as a co-principal, despite his deep involvement.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2006 decision is a landmark ruling that clarifies the essence of criminal instigation in scenarios where the lines of influence are blurred. It teaches that the act of "causing a resolution" is not limited to planting a criminal idea in a blank slate but crucially includes the act of "crystallizing" a wavering or conditional intent into a determined course of action. The person who first voices a criminal plan is not necessarily the one with the firmest resolve. Rather, the party who gives the definitive green light, whose approval is indispensable for the crime to proceed, can be the true legal instigator. This decision underscores the importance of a careful analysis of the psychological dynamics and respective roles of all parties in a complex criminal conspiracy.