The McLean Doctrine: Foreigners' Rights and Ministerial Discretion in Japanese Immigration Law

Date of Judgment: October 4, 1978, Grand Bench, Supreme Court of Japan

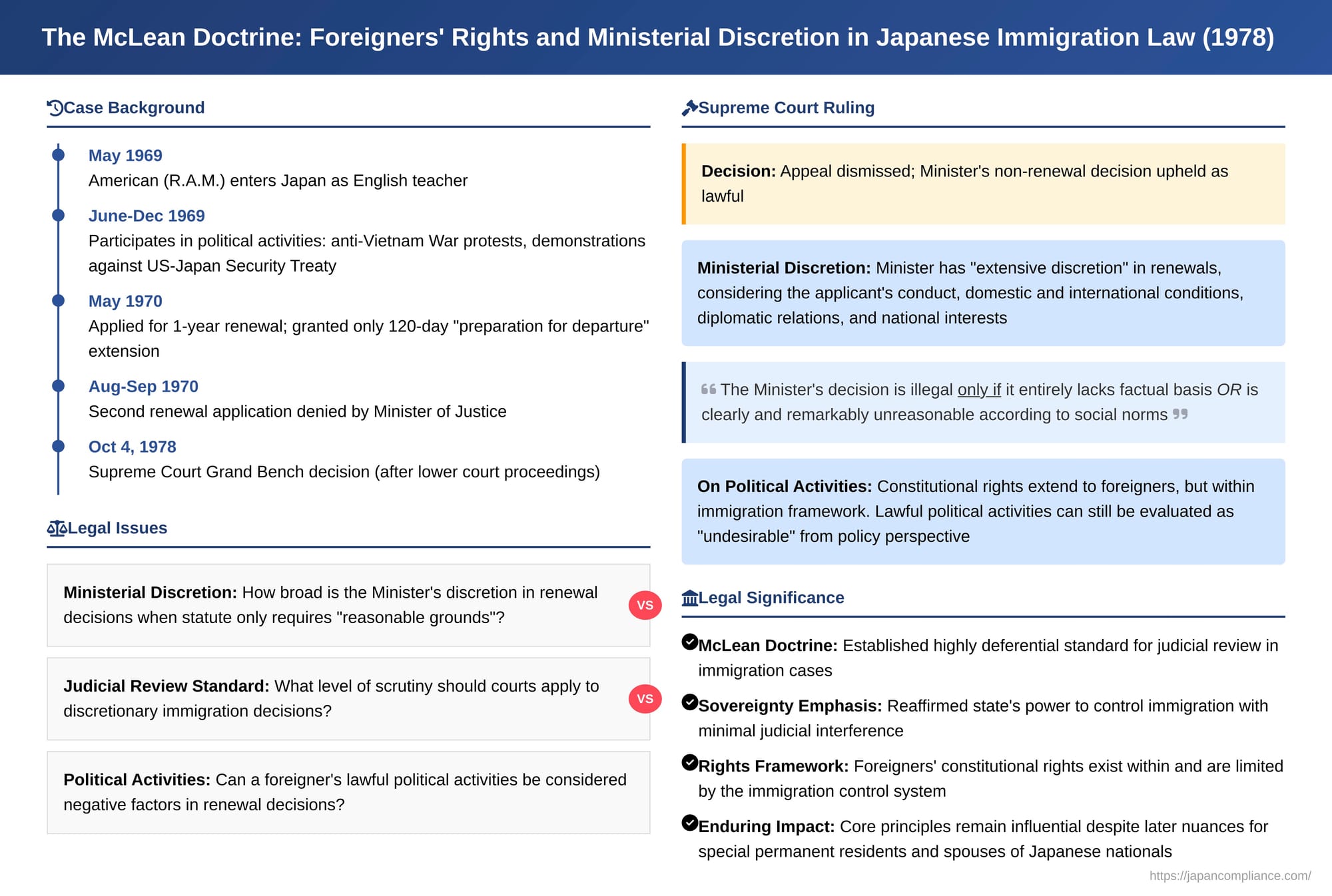

The extent of rights afforded to foreign nationals residing in a host country, particularly when juxtaposed with the state's sovereign power to control its borders and immigration, is a complex and often contentious area of law. One of the most pivotal rulings in Japan on this subject is the Supreme Court's Grand Bench decision of October 4, 1978, in what is widely known as the McLean Case[cite: 2]. This judgment profoundly shaped the understanding of ministerial discretion in immigration matters, specifically concerning the renewal of a foreign national's period of stay, and established a highly deferential standard for judicial review that continues to be influential.

The Factual Background: An American's Stay and Political Activism

The appellant, X (R. A. M.), was a citizen of the United States of America[cite: 1]. The timeline of his case is as follows:

- Entry and Initial Stay: X entered Japan in May 1969 after receiving a visa. He was granted landing permission with a one-year period of stay under a specific status (related to his employment as an English teacher at B Language School)[cite: 1].

- First Renewal Application and Limited Extension: When X applied to Y, the Minister of Justice (the Minister), for a one-year renewal of his period of stay in May 1970, he was instead granted a 120-day extension, explicitly designated as a "period for preparation for departure," effective from May 10 to September 7, 1970[cite: 1].

- Second Renewal Application and Non-Renewal Decision: Before this 120-day period expired, X applied again on August 27, 1970, for a further one-year renewal of his period of stay, to commence from September 8, 1970. On September 5, 1970, Y issued a decision (the Non-Renewal Decision) refusing to grant this renewal, stating that there were no "reasonable grounds to find it appropriate to grant the renewal"[cite: 1].

- Reasons for Non-Renewal: The Minister cited two main reasons for this decision[cite: 1]:

- Undeclared Change of Employment: X was initially granted his status to work as an English teacher at B Language School. However, he resigned from this position a mere 17 days after entering Japan and took up employment as an English teacher with the E Language Council without notifying the immigration authorities[cite: 1].

- Political Activities: During his stay, X engaged in various political activities. He was associated with the "Foreigners' P Committee" (a group of foreigners in Japan formed to oppose US involvement in the Vietnam War, Japan's perceived support for US Far East policy through the US-Japan Security Treaty, and a then-proposed Immigration Control Bill that was seen as suppressing foreigners' political activities). Between June and December 1969, X participated in nine regular meetings of this group. He also distributed leaflets supporting a hunger strike against the immigration bill, attended rallies, went to the US Embassy to protest the Vietnam War and later the US invasion of Cambodia, participated in demonstrations against the US-Japan Security Treaty, and joined a rally near a US military base. The judgment noted that all these activities were peaceful and lawful, and X's participation was not in a leading or particularly active role[cite: 1].

X challenged the Non-Renewal Decision in court. The first instance court (Tokyo District Court) ruled in his favor, finding an abuse of discretion[cite: 1]. However, the second instance court (Tokyo High Court) reversed this, upholding the Minister's decision, primarily focusing on the political activities as a legitimate, negatively considered factor within the Minister's broad discretion[cite: 1]. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: Right of Stay and Renewal in Japan

The case was decided under the Immigration Control Order (the Order, now the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act). Key legal considerations included:

- Constitutional Position of Foreigners: The Supreme Court began by affirming that Article 22, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution of Japan, which guarantees freedom of residence and movement, applies to such freedoms within Japan and does not grant foreigners a constitutional right to enter the country[cite: 1]. The Court stated that, in line with international customary law, a state is generally not obliged to admit foreign nationals and can freely determine the conditions for their entry and stay, absent specific treaty obligations[cite: 1]. Consequently, foreigners are not constitutionally guaranteed the right to enter Japan, nor do they possess a constitutional right to remain or demand continued residence[cite: 1].

- Statutory Basis for Renewal: The Order allowed a foreign national whose period of stay was expiring to apply for its renewal[cite: 1]. However, Article 21, Paragraph 3 of the Order stipulated that the Minister of Justice "may grant permission only when he/she finds that there are reasonable grounds to grant the renewal of the period of stay"[cite: 1]. The Supreme Court interpreted this to mean that the renewal of stay was not a guaranteed right even under the Order[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Decision of October 4, 1978

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the Minister's Non-Renewal Decision[cite: 1]. The Court's reasoning established several critical principles:

1. Extensive Discretion of the Minister of Justice in Renewals

The Court affirmed that the Minister of Justice possesses extensive discretion in deciding whether to renew a foreigner's period of stay:

- Broad Statutory Language: The fact that the renewal grounds in the Order were stated generally (i.e., "reasonable grounds") and that no specific criteria were laid down indicated an intention to entrust the judgment to the Minister's discretion, making its scope broad[cite: 1].

- Nature of Immigration Control: The Minister, in deciding on renewal, must consider not only the applicant's stated reasons but also their entire conduct during their stay in Japan, domestic political, economic, and social conditions, the international situation, diplomatic relations, international comity, and other relevant circumstances to maintain national interests such as public peace, good morals, public health, and labor market stability[cite: 1]. Such a comprehensive and context-sensitive judgment, the Court reasoned, is by its nature best left to the discretion of the Minister responsible for immigration control[cite: 1].

- Not Limited to Deportation Grounds: The Court explicitly stated that the Minister’s discretion for non-renewal is not limited to situations where grounds for denial of initial landing or grounds for deportation exist. The renewal process is an occasion for a fresh assessment of the foreigner's continued presence[cite: 1].

2. The Standard of Judicial Review: Highly Deferential

Given the breadth of the Minister's discretion, the Court set a very high bar for judicial intervention:

- Abuse of Discretion as the Only Ground for Illegality: An administrative disposition made within the scope of discretion is only illegal if it exceeds the legally granted scope of discretion or constitutes an abuse of that discretion[cite: 1]. Article 30 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act was cited as affirming this principle[cite: 1].

- Specific Standard for Renewal Decisions: For decisions on renewing a period of stay, the Minister's judgment as to whether "reasonable grounds" exist is illegal only if that judgment:

- Entirely lacks a factual basis (e.g., due to a misapprehension of crucial facts underlying the decision)[cite: 1], OR

- Is clearly and remarkably unreasonable according to social norms (e.g., due to a clearly irrational assessment of facts)[cite: 1].

- Presumption of Discretionary Exercise: Courts reviewing such decisions must presume they were made as an exercise of discretion and can only find illegality if one of these stringent conditions is met[cite: 1].

3. Political Activities of Foreigners and Renewal of Stay

The Court addressed the sensitive issue of X's political activities:

- Constitutional Rights of Foreigners: The fundamental human rights guaranteed by Chapter III of the Constitution extend to foreign nationals residing in Japan, except for those rights whose nature dictates they apply only to Japanese citizens. This includes freedom of political activity, excluding activities deemed inappropriate for foreigners in light of their status (such as those aiming to influence Japan's political decision-making or its implementation, or those related to the exercise of sovereign power)[cite: 1].

- Rights Within the Immigration Framework: Crucially, the Court held that these constitutional guarantees for foreigners operate within the framework of Japan's system for controlling the residence of foreign nationals. They do not extend to a guarantee that the exercise of these constitutional rights will not be considered as a negative factor by the Minister when deciding on the renewal of their period of stay[cite: 1].

- Minister's Evaluation of Lawful Activities: Even if a foreigner's activities during their stay are constitutional and lawful, the Minister is not precluded from:

- Evaluating those activities, from a policy perspective, as undesirable for Japan[cite: 1].

- Inferring from those activities that the foreigner might engage in acts detrimental to Japan's interests in the future[cite: 1].

- Application to X's Case: X's political activities, while not deemed immediately outside constitutional protection for foreigners, included criticisms of Japan's immigration policies and US Far East policy (which implicitly criticized the US-Japan Security Treaty). These actions, the Court noted, could not be said to have no potential to affect friendly relations between Japan and the United States[cite: 1]. The Minister's decision – evaluating these activities as undesirable in light of the prevailing domestic and international situation, and thereby concluding that X might in the future harm Japan's interests and that "reasonable grounds" for renewal did not exist – was found by the Supreme Court not to be based on a clearly irrational assessment of facts, nor to be clearly and remarkably unreasonable by social norms[cite: 1]. As no other circumstances indicating an overreach or abuse of discretion were established, the Non-Renewal Decision was upheld as lawful[cite: 1].

Key Takeaways and Analysis: The "McLean Doctrine"

The McLean judgment has had a profound and lasting impact, establishing what is often referred to as the "McLean Doctrine" in Japanese administrative and constitutional law regarding immigration.

1. Broad Ministerial Discretion in Immigration:

The cornerstone of the McLean Doctrine is the affirmation of exceptionally broad discretion for the Minister of Justice in matters concerning the renewal of a foreigner's period of stay[cite: 2]. This discretion is rooted in the perception of immigration control as a matter intrinsically linked to national sovereignty and requiring consideration of a wide array of policy factors[cite: 1, 3]. The commentary notes that this discretion is specifically a "requirement-recognizing discretion" (要件裁量), meaning it's exercised in judging whether the statutory condition of "reasonable grounds" is met[cite: 3].

2. Highly Restricted Judicial Review:

Consequently, the scope of judicial review is severely limited[cite: 3]. Courts will typically defer to the Minister's judgment unless it is shown to be virtually devoid of any factual basis or so irrational as to be indefensible by societal standards[cite: 1]. This standard has been described as a form of "minimal substantive review" (最小限の実体法的審査), essentially an inquiry into whether there has been a clear abuse of power[cite: 3].

3. Political Activities as a Factor:

A key aspect of the ruling is that even lawful and constitutionally permissible political activities by foreign residents can be considered negatively by the Minister when deciding on stay renewals[cite: 1]. This underscores the precarious position of foreign activists, whose exercise of fundamental freedoms might have adverse immigration consequences if their activities are perceived as contrary to Japan's national interests or foreign policy.

4. Foreigners' Rights Subordinated to Immigration Control:

The judgment clearly places the constitutional rights of foreigners within the overarching framework of the state's immigration control system[cite: 1]. While rights are recognized, their exercise does not shield a foreigner from negative discretionary decisions regarding their continued stay if the Minister deems their presence undesirable.

5. Developments Since McLean:

While the McLean Doctrine remains a bedrock principle, some later case law has introduced nuances, though without fundamentally altering the deferential standard:

- The 1998 Fingerprinting Case (Heisei 10.4.10): In a case involving the non-renewal of a re-entry permit for a special permanent resident who refused fingerprinting, the Supreme Court, while referencing McLean, noted that the Minister should also consider factors like the stability of the individual's life in Japan and the severity of the disadvantage caused by the non-renewal[cite: 3, 4]. Despite this, the Minister's decision was still upheld, suggesting that while more factors might be considered for those with deeper ties to Japan, the threshold for finding an abuse of discretion remains very high[cite: 4].

- Spouses of Japanese Nationals: In cases concerning the renewal of stay for individuals with "Spouse or Child of Japanese National" status, lower courts have sometimes shown a greater willingness to scrutinize the factual basis of decisions, particularly regarding the genuineness of marital relationships[cite: 4]. Some decisions have found an abuse of discretion, occasionally pointing to a failure by the Minister to consider relevant factors[cite: 4]. However, even if the qualifying status is confirmed, the ultimate decision on whether "reasonable grounds" for renewal exist still falls under the Minister's discretion, to be judged by the McLean standard[cite: 4].

6. Contemporary Relevance and Scholarly Critique:

The McLean judgment was delivered in 1978. Japan has since experienced significant internationalization, with a much larger and more diverse foreign population[cite: 4]. Legal scholars and commentators have questioned whether such a highly deferential standard of judicial review remains entirely appropriate in the modern context[cite: 4]. There are arguments for adopting more searching methods of review, such as examining the "decision-making process" (判断過程の審査) itself, to ensure that the Minister's broad discretion is exercised fairly and with due consideration to the often-significant impact these decisions have on individuals' lives and their connections to Japanese society[cite: 4].

Conclusion

The McLean Case stands as a critical marker in Japanese law, delineating the extensive powers of the state in immigration matters and the limited recourse foreign nationals have when challenging discretionary decisions regarding their stay. It underscores a judicial approach that prioritizes national sovereignty and executive expertise in the complex field of immigration control, while affirming that fundamental human rights for foreigners, though recognized, are not absolute and operate within the parameters set by the immigration system. While its core tenets remain influential, ongoing societal changes and evolving legal thought continue to fuel debate about the appropriate balance between state discretion and the protection of foreign residents' rights in Japan.