The Mayor's Next Term: How Japan's High Court Ruled on Bribes for Post-Re-Election Favors

The intersection of politics and public service often creates complex legal questions, especially in the realm of anti-corruption law. Consider an incumbent politician running for re-election. They wield the power of their current office while simultaneously making promises about what they will do in their next term. If that politician accepts a bribe in exchange for a promise to perform an official act after they are re-elected, what crime have they committed? Is it the serious crime of bribery by a public official, rooted in their current power? Or is it the lesser crime of bribery by a candidate, since the favor relates to a future term for which they have not yet been elected?

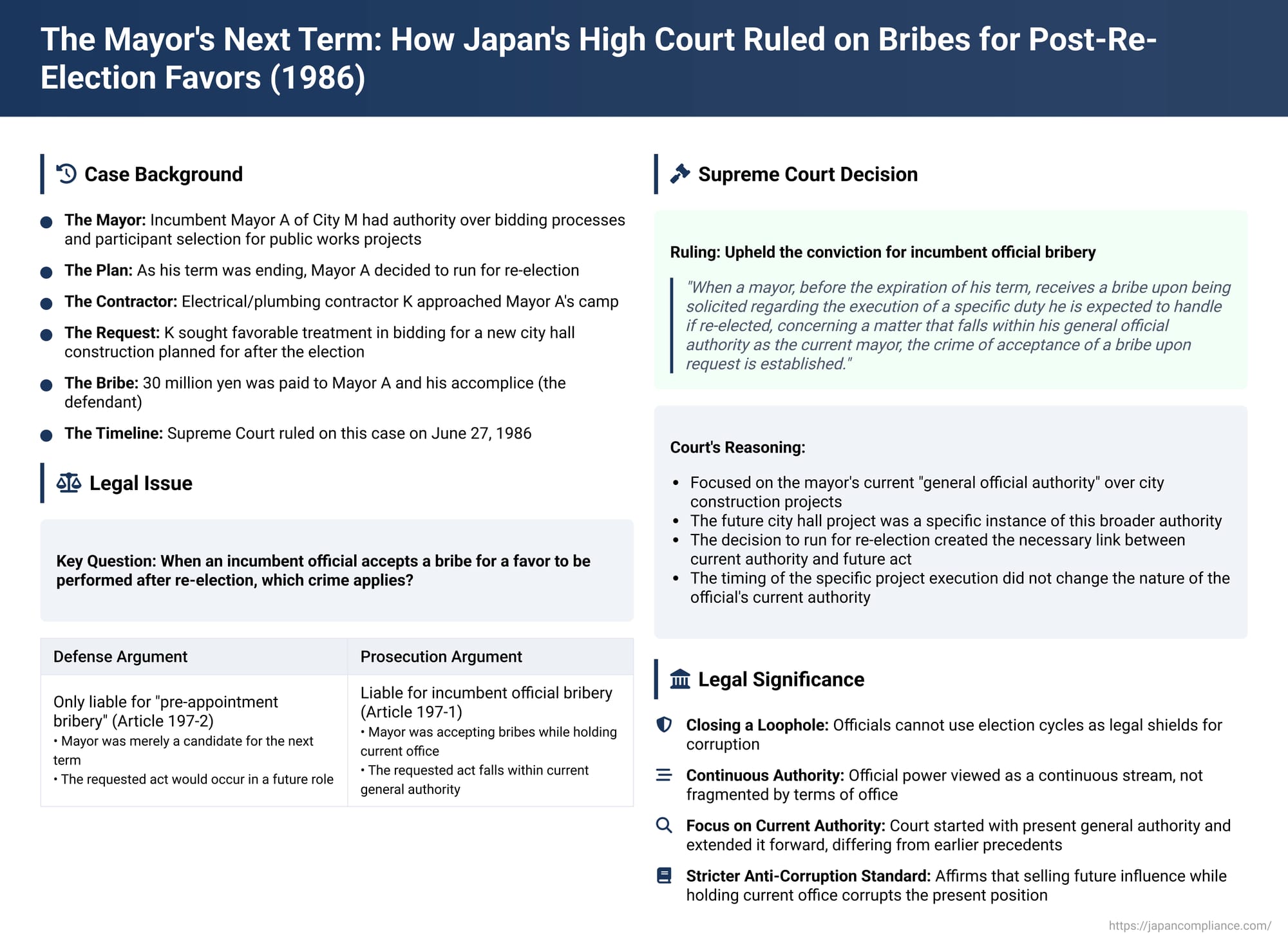

This critical question of timing, authority, and criminal intent was settled by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on June 27, 1986. The ruling clarified that an incumbent official cannot use the election cycle as a shield, establishing that a bribe for a future favor is a crime against their current office.

The Facts: The Mayor, the Bribe, and the Future City Hall

The case involved the mayor of City M, A, and an accomplice, the defendant.

- The Official's Position: Mayor A was the incumbent mayor of City M. In this capacity, he held the official authority to manage the bidding process and select participants for various public works projects commissioned by the city.

- The Political Context: As the end of his term approached, Mayor A had already solidified his decision to run for re-election in the upcoming mayoral race.

- The Quid Pro Quo: An electrical and plumbing contractor, K, approached the mayor's camp. K requested favorable treatment in the bidding and participant selection process for a new city hall construction project.

- The Crucial Timing: This major construction project was scheduled to take place after the upcoming mayoral election, during the next mayoral term. The requested favor was therefore contingent on Mayor A winning re-election.

- The Bribe: In exchange for the promise of this future favorable treatment, Mayor A, in conspiracy with the defendant, accepted a bribe of 30 million yen in cash. (Mayor A was also indicted but passed away while the case was in the first instance, and the prosecution against him was dismissed ).

The Legal Dispute: Incumbent Bribery or Candidate Bribery?

The defense's argument hinged on the timing of the promised favor.

- The Defense's Argument: They contended that since the requested act—influencing the city hall bid—concerned the next mayoral term, for which Mayor A was merely a candidate, he should only be liable under the lesser statute for "pre-appointment bribery" (Article 197, Paragraph 2 of the Penal Code), which applies to candidates for public office. They argued he could not be guilty of the more serious crime of bribery by an incumbent official (Article 197, Paragraph 1) because the specific duty was not one he currently held.

- The Lower Courts' Rulings: Both the District Court and the High Court rejected this argument. They found Mayor A guilty of the more serious crime, reasoning that he was the current mayor at the time he accepted the bribe and that there was a reasonable probability he would be re-elected and thus be in a position to carry out the favor.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Current Authority Extends to the Future

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, articulating a clear and definitive rule for such situations. The Court declared:

"When a mayor, before the expiration of his term, receives a bribe upon being solicited regarding the execution of a specific duty he is expected to handle if re-elected, concerning a matter that falls within his general official authority as the current mayor, the crime of acceptance of a bribe upon request is established."

Analysis: Linking the Present to the Future

The Supreme Court's logic is a masterclass in how bribery law adapts to the realities of political office. Instead of getting bogged down in the timing of the specific favor, the Court focused on the nature of the official's existing authority.

- The Power of "General Official Authority": The foundation of the Court's reasoning is the concept of "general official authority" (ippan-teki shokumu kengen). A bribe is illegal if it relates to any matter within an official's broad scope of power, not just a task they are specifically working on at that moment. The Court did not view the future city hall project in isolation. Instead, it started with Mayor A's current and existing general authority over "various construction projects" commissioned by the city.

- The Future Act as a Specific Instance: From this perspective, the future city hall project was not a duty of a different office, but merely a specific, future manifestation of the broad authority he already possessed. His power over "public works" was a continuous stream, and this was just one project within that stream.

- The Condition of Re-Election: The Court's logic relies on the crucial fact that there was a realistic prospect of the official continuing in office to exercise this authority. The decision explicitly notes that the mayor had already "solidified his decision to run for re-election." This fact established the necessary link between his present authority and the future act. If re-election were impossible or not contemplated, the connection would likely be severed, and the act might indeed fall under the pre-appointment bribery statute.

- A Different Logic from Past Precedent: This approach is subtly different from some earlier precedents. For example, in a 1961 case involving a tobacco inspector bribed for a future season's work for which he was not yet appointed, the court started with the specific future act and worked backward to find a present "abstract authority" to be appointed. The 1986 decision, in contrast, starts with the official's broad present general authority and looks forward to encompass a future act that falls under that same general umbrella.

Conclusion

The 1986 Supreme Court decision provides a clear and lasting precedent for how bribery law applies to incumbent officials who trade on their future influence. It establishes that such an act is not the lesser crime of pre-appointment bribery but is a crime committed against their current office. The key is that the future favor must fall under the umbrella of the official's existing "general official authority," and there must be a realistic prospect—such as a planned re-election bid—that the official will continue in a position to exercise that authority.

The ruling sends a strong and unambiguous anti-corruption message: an official cannot use the timing of an election cycle as a legal shield. The act of selling the power of a future office while still occupying the current one is a corruption of the present office. The law, in this regard, views an official's authority not in fragmented terms, but as a continuous whole, conditioned only by the political reality of their continued service.