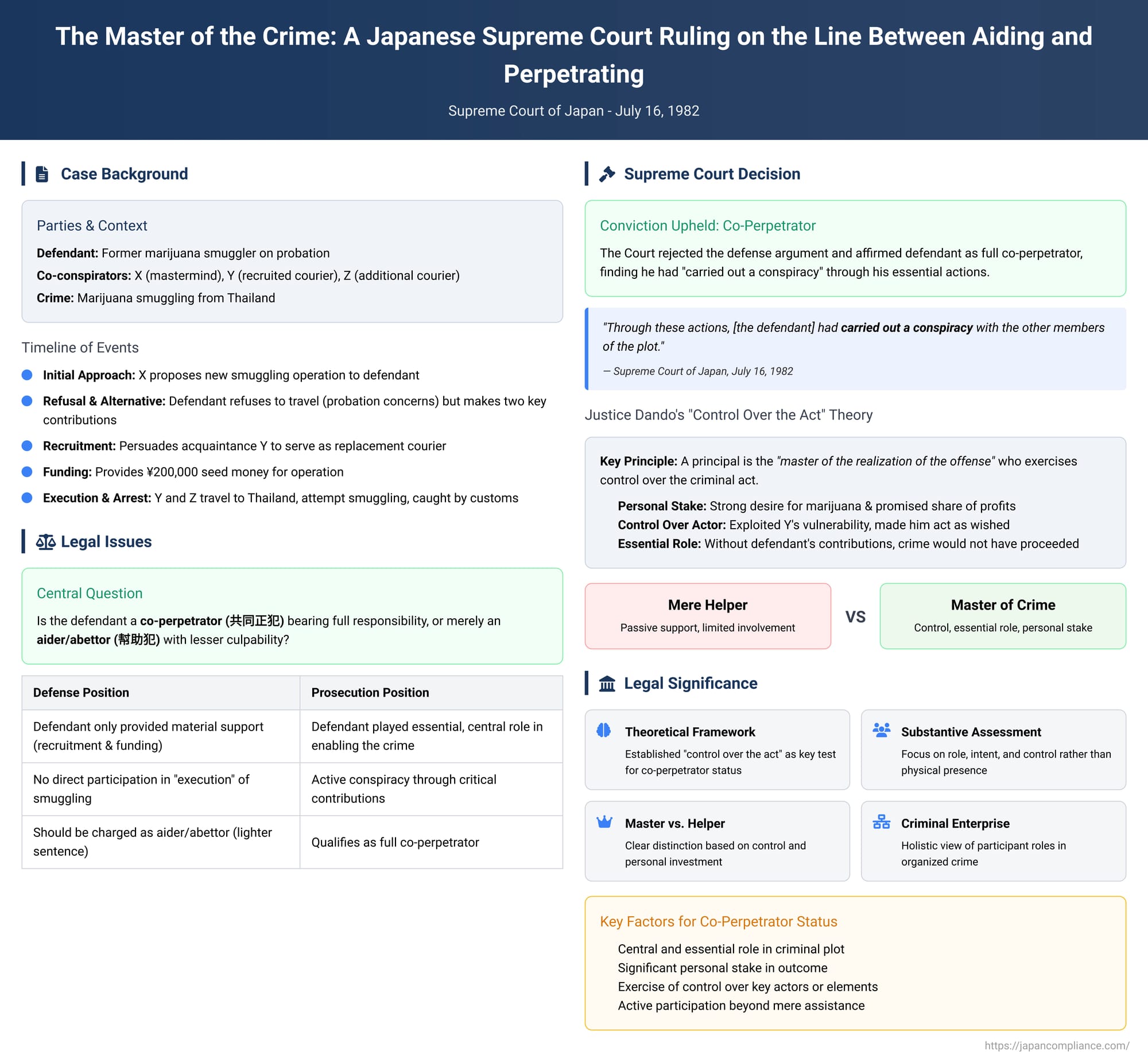

The Master of the Crime: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on the Line Between Aiding and Perpetrating

In any criminal enterprise, participants play different roles. Some plan, some finance, and others execute. This raises a fundamental question for the law: who is a principal perpetrator, bearing full responsibility for the crime, and who is a mere "helper" or accessory, whose culpability is lesser? On July 16, 1982, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed this blurry line in a case involving a marijuana smuggling plot. The decision, notable for a detailed concurring opinion from one of Japan's most famous legal scholars-turned-justices, provides a powerful framework for understanding who qualifies as a "master of the crime."

The Facts: The Reluctant Smuggler's Deputy

The defendant was a man with a history of smuggling marijuana from Thailand alongside an acquaintance, X. When X approached him with a new plan for another smuggling run, the defendant was eager to get more marijuana but was hesitant to travel himself because he was currently on probation for a prior offense.

He refused to be the courier, but he did not walk away. Instead, he made two crucial contributions to the criminal plot:

- He recruited a replacement. The defendant approached another acquaintance, Y, explained the smuggling plan, and persuaded him to take his place as the courier who would travel to Thailand. He then introduced Y to the mastermind, X.

- He provided seed money. He gave X 200,000 yen to be used as part of the funds for the smuggling operation.

In exchange for this assistance, the defendant was promised a share of the imported marijuana commensurate with his financial contribution. Following this agreement, the plan was set in motion. Y, along with another recruit, Z, traveled to Thailand, purchased the marijuana, and attempted to smuggle it into Japan, where they were ultimately caught by customs officials.

The Legal Question: Aider and Abettor, or Co-Perpetrator?

The defendant was charged as a full co-perpetrator (共同正犯 - kyōdō seihan) of the smuggling crimes. His defense argued that this over-stated his role. They contended that his actions—recruiting a replacement and providing funds—were not the "execution" of the smuggling itself. They were acts of material support that merely made the crime easier for the principals (X, Y, and Z) to commit. Therefore, he should be treated as an accessory or an aider and abettor (幇助犯 - hōjohan), a distinct legal category that carries a lighter sentence. The question for the Supreme Court was whether the defendant's contributions were substantial enough to make him a principal in the crime.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Conspiracy of Action

The Supreme Court rejected the defense's argument and affirmed the conviction, finding that the defendant was indeed a co-perpetrator. The Court looked at the defendant's actions holistically and concluded that "through these actions," he had "carried out a conspiracy" (bōgi wo togeta) with the other members of the plot.

The Court did not see a passive helper. It saw a proactive participant who, despite refusing to perform one specific role (the courier), played a central part in ensuring the crime could move forward. By finding his own replacement and providing essential funding in exchange for a share of the criminal proceeds, he had demonstrated a deep, personal investment in the success of the enterprise. This active and essential participation elevated him beyond the status of a mere accessory.

The Scholar on the Bench: Justice Dando's "Control Over the Act" Theory

What makes this decision particularly significant is a detailed concurring opinion from Justice Dando, a towering figure in Japanese legal scholarship who had, before joining the bench, been a prominent critic of the Court's broad application of conspiracy liability. In his opinion, he laid out a clear theoretical foundation for why this defendant was, in fact, a principal perpetrator. This theory is known as the "control over the act" (行為支配説 - kōi shihai setsu) doctrine.

Justice Dando argued that a principal is not just someone who physically acts, but someone who is the "master of the realization of the offense." To be a principal, a person must have control over the criminal act itself.

He then masterfully applied this test to the defendant's actions:

- The Personal Stake: The defendant's strong desire for the marijuana and his arrangement to receive a share of the profits were crucial. This showed that, for him, "the crime was his own crime." This personal interest is a key indicator of a "master" rather than a mere helper.

- The Control Over the Actor: Justice Dando delved into the relationship between the defendant and Y, the replacement he recruited. Y was younger, the defendant had mentored him, and Y was deeply disappointed after a planned trip abroad had been canceled. The defendant exploited this vulnerability, luring Y with the promise of a "free trip to Bangkok" to serve as his substitute.

In Justice Dando's view, the defendant did not just assist the crime; he "made Y act as he wished." He controlled a key actor like a puppet, making him an instrument of his own criminal will. Therefore, the defendant, along with the mastermind X, was a "master of the crime" who controlled its execution.

Conclusion: Defining the Modern Co-Perpetrator

The 1982 decision is a crucial guidepost in the law of criminal complicity. It affirms that being a co-perpetrator does not require physical presence or performance of the final act. The legal determination rests on a substantive assessment of the individual's role, intent, and, most importantly, control.

Did the person play a central and essential role in the plot? Did they have a significant personal stake in the outcome? And, as Justice Dando's influential opinion articulates, did they exercise a form of "control over the act," effectively making the crime their own? This case demonstrates that providing critical resources and recruiting key personnel, all while motivated by personal gain, elevates a person from a mere helper to a master of the crime, fully responsible for its outcome in the eyes of the law.