The MacLean Doctrine: Japan's Supreme Court on Foreigners' Rights, Political Activity, and Visa Renewal

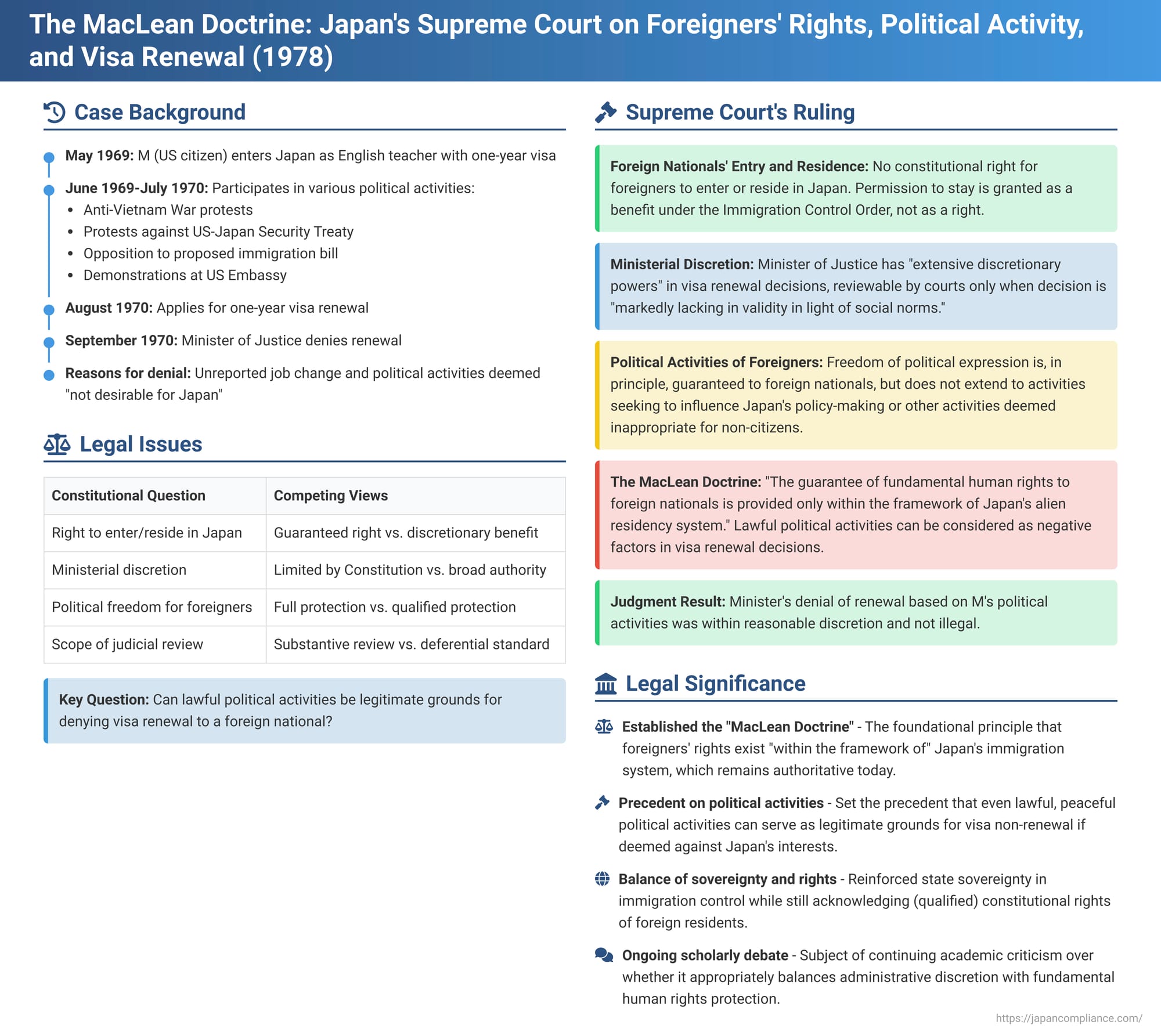

The authority of a sovereign state to control the entry and stay of foreign nationals within its borders is a fundamental aspect of international law and national policy. In Japan, a landmark decision by the Supreme Court on October 4, 1978, in what is commonly known as the MacLean case, profoundly shaped the understanding of this authority. This judgment meticulously delineated the extent of foreigners' constitutional rights in relation to the state's discretionary powers in immigration matters, particularly concerning the renewal of periods of stay and the implications of political activities undertaken by foreign residents. The MacLean case remains a cornerstone of Japanese jurisprudence on the legal status of foreigners.

The Case of M: An English Teacher's Political Engagement and Visa Denial

The appellant, M, was a citizen of the United States who entered Japan in May 1969. He was granted a one-year period of stay under a specific visa status, initially linked to his employment as an English teacher at a designated language school. Beyond his professional life teaching English, M also immersed himself in Japanese culture, notably studying traditional Japanese music, including the Biwa and Koto.

After his initial year, M applied for an extension of his period of stay to continue his employment and cultural pursuits. He was first granted a short, 120-day extension explicitly for "departure preparation," running from May 10 to September 7 of the following year. Before this period expired, on August 27, M applied for a further one-year extension from September 8. However, on September 5, the Minister of Justice (the appellee) issued a disposition denying this renewal application.

The Minister's reasons for deeming that there were no "reasonable grounds to find the renewal appropriate" were twofold:

- Unreported Change of Employment: M had changed his employer shortly after his arrival in Japan. He left the language school for which his initial visa status was approved after only about 17 days and began working for a different English teaching foundation without formally reporting this change to the immigration authorities as required.

- Political Activities: This was the more significant and contentious basis for the denial. During his stay, M engaged in various political activities. He was associated with a group of foreign nationals ("Gaikokujin Beheiren") which, according to the judgment, was formed with three objectives: opposing American military intervention in Vietnam, opposing Japan's complicity in American Far East policy through the US-Japan Security Treaty (often referred to as "Anpo"), and opposing a proposed immigration bill perceived as suppressive of foreigners' political activities. The specific political actions attributed to M included:It was noted, both in the case summary and acknowledged by the courts, that all of M's participations in these assemblies and demonstrations were peaceful, remained within legal boundaries, and his role was neither that of a leader nor of a particularly active instigator.

- Attending nine regular meetings of this group between June and December 1969.

- On July 10, 1969, distributing leaflets publicizing the aims of a hunger strike conducted by other groups near Shinjuku Station against the proposed immigration bill.

- Participating in protests directed at the US Embassy against the Vietnam War, notably during the "Vietnam Moratorium Day" events.

- Joining a demonstration aimed at protesting conditions at an immigration detention center in Yokohama in December 1969.

- Attending an anti-war broadcast rally in Asaka city in February 1970, and an anti-war demonstration near the US Army's Camp Drake in the same city in March 1970.

- Distributing anti-war leaflets at a citizens' gathering in Asaka in March 1970, alongside the aforementioned group.

- Protesting at the US Embassy against the US invasion of Cambodia in May 1970.

- Participating in a Japan-US people's rally and demonstration against the Cambodian intervention in May 1970.

- Attending a large-scale rally in Yoyogi Park in June 1970 aimed at "smashing" the US-Japan Security Treaty.

- Participating in a rally in Shimizu-dani Park, Tokyo, in July 1970, organized to support solidarity between Japanese and American people and anti-war US soldiers.

- Engaging in activities at Haneda Airport protesting the arrival of the then-US Secretary of State, William P. Rogers, in July 1970.

The Legal Battles: Lower Courts Divided on Discretion and Rights

M challenged the Minister's decision, leading to differing outcomes in the lower courts.

The Tokyo District Court:

The District Court, in its ruling, acknowledged that the Minister of Justice possesses "considerably broad discretionary powers" when deciding on applications for the renewal of a period of stay. However, it emphasized that this discretion is not unfettered and must be exercised within the bounds established by the Constitution and other applicable laws.

Specifically addressing M's political activities, the District Court found that it "goes without saying" that these actions should not be viewed as posing a threat to the interests of Japan or its people. Consequently, the court concluded that the Minister's decision to deny the renewal based on these activities was "markedly lacking in validity in light of social norms" and therefore constituted an abuse of discretion. The District Court revoked the Minister's non-renewal disposition.

The Tokyo High Court:

The Minister of Justice appealed to the Tokyo High Court, which took a significantly different view, placing greater emphasis on state sovereignty in immigration matters. The High Court proclaimed that whether or not to admit a foreign national into its territory is "fundamentally a matter of that country's freedom."

Regarding visa renewals, the High Court stated that the determination of whether "reasonable grounds exist to deem the renewal appropriate" is entrusted to the "free discretion of the Minister of Justice." It reasoned that if the Minister, after reviewing M's series of political activities, judged them to be "not desirable for Japan and the Japanese people," and on that basis concluded that there were no sufficient reasonable grounds for renewal, this judgment fell within the scope of discretion legitimately granted to the Minister. This was held to be the case, particularly where there were no circumstances indicating that the Minister's decision was patently unreasonable to any objective observer.

Thus, the Tokyo High Court overturned the District Court's ruling and dismissed M's claim, thereby upholding the Minister's decision to deny the visa renewal. M subsequently appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Defining the Boundaries

The Supreme Court, in its Grand Bench judgment, delivered a comprehensive analysis of the legal principles governing the stay of foreigners in Japan, the scope of ministerial discretion, and the extent of constitutional rights applicable to foreign nationals. The Court ultimately dismissed M's appeal.

1. Foreigners' Entry and Right of Residence

The Court first addressed the fundamental question of whether foreign nationals possess a constitutional right to enter or reside in Japan.

- It interpreted Article 22, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution of Japan, which guarantees "freedom of all persons to move to a foreign country and to divest themselves of their nationality" and "freedom of all persons to choose and change their residence," as pertaining to the freedom of Japanese nationals to choose their residence within Japan and to move abroad. It held that this article does not grant foreigners any right to enter Japan.

- This interpretation, the Court noted, is consistent with established principles of customary international law, under which a state is not obliged to admit foreign nationals into its territory. Absent specific treaty provisions, each state retains the sovereign power to freely decide whether to admit foreigners and, if so, under what conditions. The Court referenced its own 1957 Grand Bench precedent in support of this view.

- Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that foreign nationals are not guaranteed the freedom to enter Japan under the Constitution. Furthermore, they do not possess a constitutionally guaranteed "right of residence" or a right to demand continued stay in Japan. Any permission to stay in Japan is granted not as a right but as a benefit under the provisions of the Immigration Control Order (formally, the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, which was at the time the Immigration Control Order – Shutsunyūkoku Kanri Rei).

2. The Minister of Justice's Discretion in Renewing Periods of Stay

The Supreme Court then examined the nature and scope of the Minister of Justice's authority in deciding applications for the renewal of a period of stay.

- The Court observed that the Immigration Control Order (specifically Article 21, Paragraph 3, which stipulated that the Minister may grant a renewal "only when he finds that there are reasonable grounds to deem the renewal of the period of stay appropriate on the basis of the application") is intentionally structured to grant the Minister considerable leeway.

- The legislative intent, according to the Court, was to enable the Minister to periodically review the foreign national's conduct during their stay in Japan, the ongoing necessity and appropriateness of their continued presence, and other relevant circumstances to determine whether to permit further stay.

- The grounds for renewal are broadly defined ("reasonable grounds to find it appropriate"), and specific, exhaustive criteria are not enumerated in the statute. The Court interpreted this as a deliberate legislative choice to entrust the determination to the Minister's extensive discretionary powers.

- In exercising this discretion, the Minister is expected to consider a wide array of factors. These include not only the applicant's stated reasons for wishing to stay but also their entire conduct while in Japan, the prevailing domestic political, economic, and social conditions, Japan's international relations, diplomatic considerations, and international comity. Such a multifaceted and sensitive judgment, often involving policy considerations, is best left to the discretion of the Minister of Justice, who bears the primary responsibility for immigration control and national security.

- Limits on Discretion and Scope of Judicial Review: While this discretion is broad, it is not absolute or immune from judicial scrutiny. However, the threshold for a court to overturn the Minister’s decision is very high. A court can only find the Minister’s decision illegal if it is demonstrated that:

- The decision is based on a critical misunderstanding of key facts, leading to a judgment that lacks any factual basis.

- The evaluation of the facts upon which the decision is based is clearly irrational, rendering the judgment "markedly lacking in validity in light of social norms."

- Only if such egregious flaws are evident can the decision be deemed an abuse or an overstepping of the discretionary powers conferred by law.

3. Foreigners' Fundamental Human Rights and the Alien Residency System: The "MacLean Doctrine"

This part of the judgment is arguably its most significant and has come to be known as the "MacLean Doctrine."

- General Guarantee of Rights: The Supreme Court affirmed the principle that the fundamental human rights protections enshrined in Chapter 3 of the Japanese Constitution are, as a general rule, extended to foreign nationals residing in Japan. The exception concerns those rights that, by their inherent nature, are understood to apply exclusively to Japanese citizens (e.g., the right to vote in national elections or hold public office, which are directly linked to the sovereignty of the Japanese people).

- Political Activities of Foreigners: Specifically addressing the freedom of political activity, the Court stated that this freedom is also, in principle, guaranteed to foreign nationals. However, this guarantee is not unlimited. It does not extend to:

- Activities that seek to influence Japan's governmental policy-making or its implementation.

- Other political activities that are deemed inappropriate for foreign nationals in light of their status as non-citizens and guests in the country.

- The Crucial Qualification – "Within the Framework of the Alien Residency System": The Court then introduced its most pivotal and subsequently most debated pronouncement: The constitutional guarantee of fundamental human rights to foreign nationals is provided only within the framework of Japan’s alien residency system.

- This means that because the right to enter and reside in Japan is not a constitutionally guaranteed right for foreigners, but rather a status granted under the Immigration Control Order (contingent upon the Minister's discretionary approval for initial entry and subsequent renewals), the scope of their other constitutional rights is inherently linked to this system.

- Therefore, the protection of human rights for foreigners does not extend so far as to restrict or negate the state's discretion in deciding whether to permit their initial entry or continued residence.

- Implication for Renewal Decisions: The direct and critical consequence of this reasoning is that even if a foreign national engages in activities that are, in themselves, constitutionally protected (such as freedom of speech or political expression) and entirely lawful during their permitted period of stay, those very activities can still be considered as negative factors by the Minister of Justice when deciding on an application for renewal of the period of stay.

- The Court elaborated that even if a foreigner’s actions during their stay are constitutional and legal, the Minister of Justice is entitled to evaluate those actions from the broader perspective of national interest (e.g., whether they are desirable for Japan or its people). The Minister can also infer from such actions a potential future risk that the foreigner might act in a manner detrimental to Japan's interests. This assessment, and a subsequent denial of renewal based on it, is not precluded simply because the actions themselves fell within the ambit of the foreigner's protected rights during their authorized stay.

- Application of these Principles to M’s Case:

- The Supreme Court acknowledged that M's political activities, considering their nature and the manner in which they were conducted (peaceful, non-leading), could not immediately be classified as falling outside the scope of constitutionally protected political expression that might be permissible for foreign nationals.

- However, the Court noted that some of M's activities included direct criticism of Japan's official immigration policies (e.g., the proposed immigration bill) and its fundamental foreign policy, notably his protests against the US-Japan Security Treaty. The Court viewed these as actions that could potentially strain or negatively affect the friendly relations between Japan and the United States.

- The Minister of Justice, taking into account the prevailing domestic and international situation at the time, had assessed M's political activities as being "not desirable for Japan." The Minister also inferred from these activities that M posed a potential risk of acting contrary to Japan's interests in the future. Based on this overall assessment, the Minister concluded that there were no "reasonable grounds to deem the renewal appropriate."

- The Supreme Court held that this evaluation of facts by the Minister was not "clearly irrational," nor was the resulting judgment "markedly lacking in validity in light of social norms." Furthermore, the Court found no evidence to suggest that the Minister had overstepped or abused his discretionary powers in reaching this conclusion.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the Minister's decision to deny M's visa renewal was not illegal. It also held that no constitutional issues arose from the Minister's consideration of M's political activities as a negative factor in this decision-making process, given the qualified nature of foreigners' rights within the residency system.

The "MacLean Doctrine": Enduring Legacy and Ongoing Debate

The MacLean judgment of 1978 established what has come to be known as the "MacLean Doctrine," a set of principles that have become foundational in Japanese law concerning the legal status of foreign nationals. At its heart, the doctrine posits that while foreign nationals residing in Japan are beneficiaries of constitutional human rights protections, these rights are circumscribed by, and operate within, the state's overarching discretionary power over immigration matters.

The most striking tenet of this doctrine is that activities undertaken by a foreign national during their authorized period of stay, even if those activities are entirely lawful and fall within the scope of constitutionally protected expressions of fundamental rights (such as freedom of speech or political assembly), can nevertheless legitimately form the basis for a negative decision in a visa renewal application. This is permissible if the Minister of Justice, in their broad discretion, deems those activities contrary to Japan's national interests or indicative of a potential for future conduct that could be detrimental to the country.

This ruling has exerted a profound and lasting influence on subsequent Japanese jurisprudence. It has been consistently cited and applied in a wide range of cases involving foreigners' rights, extending beyond visa renewals to issues such as political participation, conditions for re-entry permits (for example, in cases where resident foreigners refused mandatory fingerprinting as a condition for re-entry permits in the past), and deportation proceedings. The "within the framework of the alien residency system" logic has frequently been invoked to uphold broad administrative discretion in immigration control.

However, the MacLean Doctrine has not been without its critics, particularly within academic legal circles. Some scholars argue that it effectively prioritizes the state's immigration control apparatus and its discretionary powers over the robust protection of fundamental human rights for individuals, regardless of their nationality. This can create a hierarchy where the guarantee of rights becomes secondary to administrative convenience or broadly defined, sometimes vaguely articulated, notions of "national interest." There have been ongoing scholarly discussions and critiques questioning whether the balance struck by the MacLean Court remains appropriate, especially in light of evolving international human rights norms that increasingly emphasize the protection of all individuals within a state's jurisdiction, with limited and clearly defined exceptions.

The debate often centers on how to ensure that the extensive discretion granted to immigration authorities does not become a tool for arbitrary decision-making. Critics call for clearer, more objective criteria for immigration decisions, particularly those that negatively impact foreign residents, and advocate for more meaningful and substantive judicial review when fundamental rights are implicated. The challenge lies in reconciling the state's legitimate interest in controlling immigration with its equally important obligation to uphold the human rights of all individuals under its jurisdiction.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the MacLean case on October 4, 1978, remains a pivotal and frequently cited authority in Japanese immigration law. It firmly established the principle of extensive state discretion in managing the entry and continued stay of foreign nationals, affirming that there is no inherent constitutional right for non-citizens to enter or reside in Japan.

Most significantly, the MacLean case articulated the doctrine that while foreign nationals are indeed entitled to the protection of fundamental human rights under the Japanese Constitution, this protection is qualified by, and operates "within the framework of," the alien residency system. This implies that lawful political activities, or the exercise of other constitutional rights, if deemed undesirable or contrary to national interests by the Minister of Justice, can serve as valid grounds for denying a renewal of the period of stay. The MacLean doctrine continues to shape the legal landscape for foreign nationals in Japan, representing a complex balance between individual rights and the state's sovereign prerogative to control its borders and define the conditions under which foreign nationals may reside within its territory.