The Lookout's Winnings: A Japanese Ruling on the Scope of Theft in a Conspiracy

Imagine a casino heist. A team conspires to cheat at the slot machines. One member, the technician, uses a device to force a machine to pay out jackpots. Another member, the lookout, sits at an adjacent machine and plays normally, acting as a "wall" to block the view of security cameras and staff. If the lookout, while playing legitimately, happens to win a jackpot of their own, are those winnings considered part of the stolen loot? Does their participation in the criminal conspiracy automatically taint their otherwise legal actions?

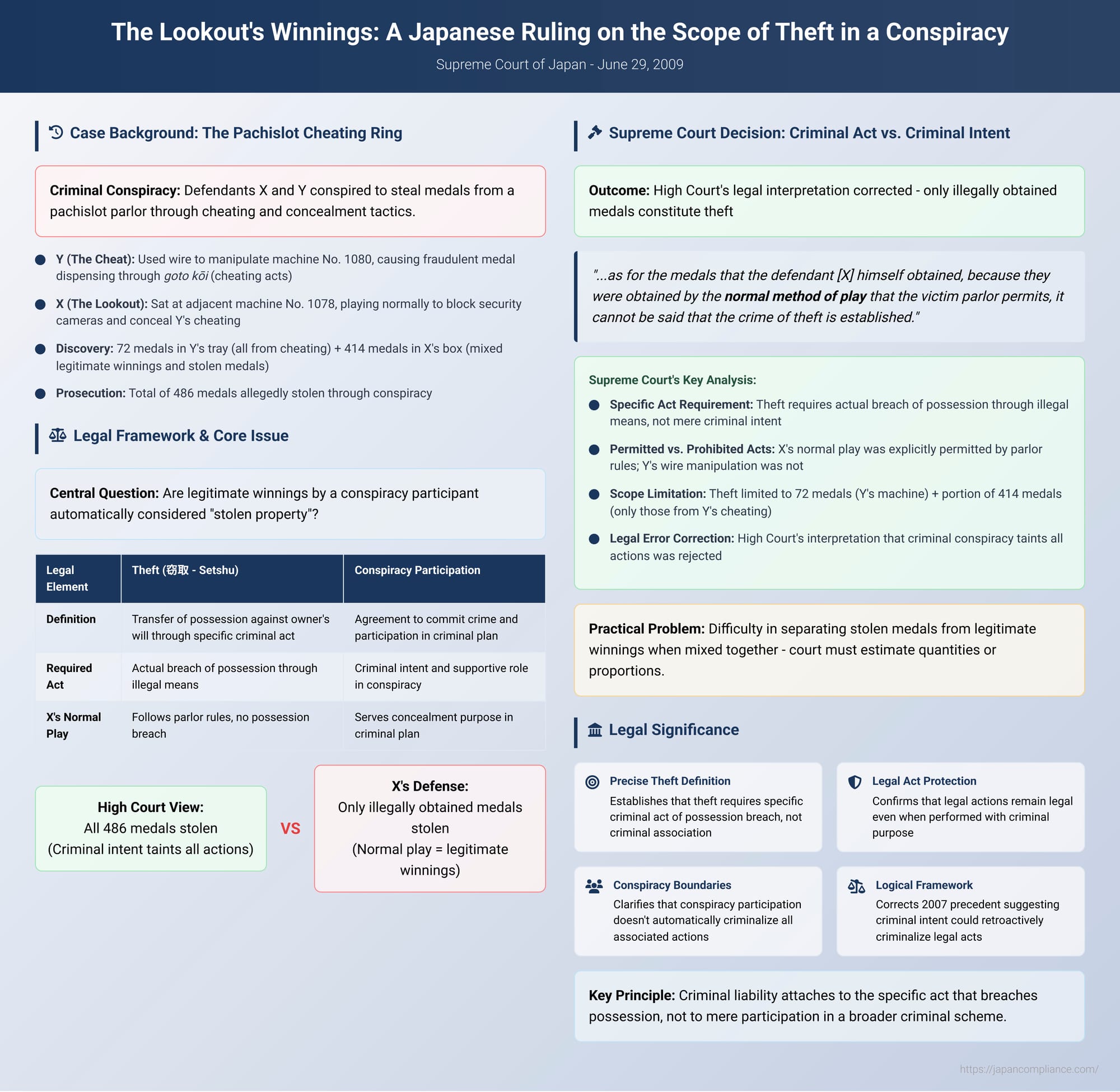

This fascinating question was at the heart of a decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on June 29, 2009. The case, involving a cheating ring at a pachislot (a Japanese slot machine) parlor, forced the Court to draw a fine line, clarifying that the crime of theft is tied to the specific criminal act of taking, not to mere participation in a broader conspiracy. The ruling provides a crucial lesson on the precise legal definition of "theft."

The Facts: The Pachislot Cheating Ring

The case involved a criminal conspiracy between the defendant, X, an accomplice, Y, and others to steal medals from a pachislot parlor. Their roles were clearly defined:

- The Cheat (Y): Y sat at a pachislot machine (No. 1080) and used a wire to manipulate its internal workings, causing it to dispense medals fraudulently. This act of cheating is known in Japanese as goto kōi.

- The Lookout (X): The defendant, X, had the specific job of concealing Y's cheating from parlor staff and security cameras. To accomplish this, he sat at the machine directly next to Y's (No. 1078) and played in a completely normal fashion.

The plan was to pool all the medals they acquired—both those Y obtained through cheating and those X won legitimately—cash them in for prizes, and split the profits evenly among the conspirators.

When the crime was discovered and the conspirators were apprehended, the medals were found in two places. Y's machine had 72 medals in its lower tray, all of which were the result of his illegal cheating. At X's station, there was a large box (doru-bako) on his lap containing 414 medals. This box contained a mix of medals that X had won through his own normal play, combined with medals that Y had obtained through cheating.

The Legal Definition of Theft (Setshu)

The core legal question was how to define the scope of the theft. The crime of theft in Japan is established by an act of setshu, which is legally defined as transferring the possession of property from its current possessor to oneself or a third party, against the will of the possessor.

While Y's act of using a wire to manipulate the machine clearly constituted setshu, the question for the court was how to treat X's winnings. Was X's own act of playing normally also an act of setshu?

The Lower Court's Broad Interpretation

The Sendai High Court, which heard the case on appeal, took a very broad view. It found the defendant, X, guilty of stealing all 486 medals (the 72 from Y's machine and the entire 414 from his own mixed box).

The High Court's reasoning was that X's act of playing, even though it followed the rules, was an inseparable part of the overall criminal conspiracy. Because his purpose was to facilitate the crime, the court concluded that the parlor had obviously not consented to him winning any medals, even through legitimate play. In this view, the criminal conspiracy tainted all of X's actions, turning his legitimate winnings into stolen property.

The Supreme Court's Crucial Correction

The defendant appealed to the Supreme Court. While the Court ultimately rejected the appeal on procedural grounds, it used its authority to correct the fundamental legal error in the High Court's reasoning.

The Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court's broad interpretation. It drew a sharp distinction between participating in a conspiracy and committing the specific act of theft. The Court's landmark principle was stated clearly:

"...as for the medals that the defendant [X] himself obtained, because they were obtained by the normal method of play that the victim parlor permits, it cannot be said that the crime of theft is established."

This was a critical clarification. The Supreme Court ruled that to determine if an act is theft, one must analyze the specific act that caused the transfer of possession. X's own act of playing was normal and permitted by the parlor's rules. Y's act of using a wire was not. Therefore, only the medals that resulted directly from Y's illegal act were stolen. The medals X won himself were his legitimate winnings, regardless of his criminal state of mind or his role in the broader conspiracy.

The Court concluded that the High Court had "erred in its interpretation and application of the law regarding the infringement of possession in the crime of theft". The scope of the theft, the Supreme Court clarified, was limited to the 72 medals in Y's tray plus an unspecified portion of the 414 medals in X's box (specifically, the portion that had come from Y's cheating).

Despite this significant legal correction, the Court did not overturn the final conviction. It reasoned that since X was a co-principal in Y's theft of a "considerable number" of medals, the lower court's error in calculating the total amount stolen was not severe enough to warrant a reversal of the judgment under the specific circumstances.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision is vital for its precise definition of the act of theft. It rejects the notion that a person's criminal intent can retroactively transform a legal act into a criminal one. The key is the nature of the act itself.

This ruling provides a welcome clarification to a more ambiguous 2007 Supreme Court decision. In that earlier case, which involved a player using an electronic device to predict winning patterns, the Court had controversially suggested that the player's entire session of play, even before using the device, could be considered theft because they entered the parlor with the intent to cheat.

The 2009 decision, by contrast, establishes a more logical and defensible standard. It teaches that criminal liability for theft attaches to the specific act of setshu—the act that breaches the owner's possession against their will. In this case, the setshu was Y's use of the wire. X's own play, while performed with a criminal purpose, did not breach the rules of the game and therefore was not an act of setshu.

The case also raised the practical problem of how to identify the stolen property when it is mixed with legitimate property. The commentary on the case suggests that the correct approach, rather than declaring the entire mixture stolen, is for the court to identify the stolen portion by its quantity or proportion, even if it is an estimate, which is what the Supreme Court indicated should have been done.

Conclusion

The 2009 "lookout" case is a cornerstone ruling that refines the legal understanding of theft in Japan. It makes clear that guilt is not determined by a person's association with a criminal plan, but by their commission of a specific criminal act. An otherwise legal action, such as playing a slot machine by the rules, does not become theft simply because it is performed in support of another person's crime.

The decision provides a more precise and logically sound framework for assessing theft, ensuring that criminal liability is correctly targeted at the act that actually violates the owner's possession and the rules of the game. It confirms that even in the midst of a criminal plot, an act that is legal on its face remains legal, a principle with wide-ranging implications for the law of conspiracy and property crime.