The Long Reach of Obstruction: When an Attack on a Private Citizen is a Crime Against the State

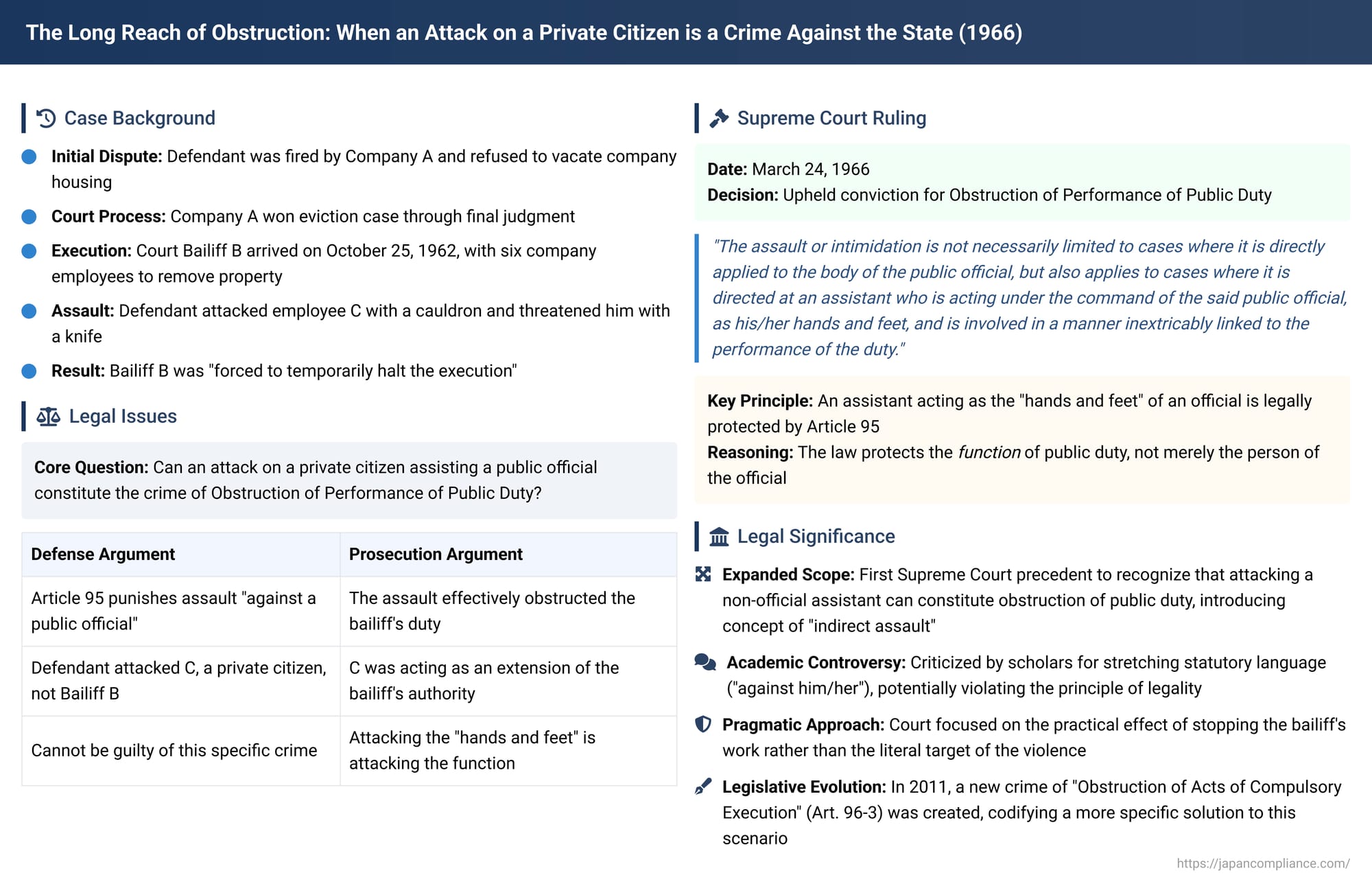

The crime of Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty is designed to protect the very functioning of the state. It ensures that public officials, from police officers to court bailiffs, can carry out their lawful responsibilities without being hindered by violence or threats. But what are the limits of this protection? If an official is using private citizens as assistants—for example, movers during a court-ordered eviction—is an attack on one of those private citizens a crime against the state? Or is it merely a private act of assault, since the victim was not a public official?

This critical question, which tests the boundaries of what it means to obstruct a public duty, was definitively answered by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on March 24, 1966. The ruling established that an attack on a non-official assistant can indeed constitute a criminal obstruction of a public duty, provided that assistant is acting as the "hands and feet" of the public official.

The Facts: The Eviction and the Attack on the Mover

The case began with a civil dispute that escalated into a criminal confrontation.

- The Background: The defendant had been fired by his employer, Company A, but refused to vacate the company-owned house he had been living in. Company A sued him and won a final court judgment for eviction.

- The Eviction: When the defendant still refused to leave, the company entrusted the matter to a court bailiff, B, to carry out a compulsory execution of the eviction order. On the morning of October 25, 1962, Bailiff B arrived at the house to begin the process. To carry out the physical removal of the defendant's property, he brought with him six employees of Company A, including a man named C, to act as laborers under his direction.

- The Assault: At around 11:00 AM, as C was carrying a cauldron out of the kitchen, the defendant confronted him. The court found that the defendant was fully aware that C was acting as an assistant under the command of Bailiff B. The defendant grabbed the cauldron from C and used it to strike C on the head and left arm. He then retrieved a kitchen knife, threatened C with it, shouting "I'll kill you," and inflicted minor injuries.

- The Obstruction: This violent confrontation, directed at the mover C, caused Bailiff B, who was directing the entire operation from the doorway, to be "forced to temporarily halt the execution."

The Legal Defense: "I Didn't Touch the Bailiff"

The defendant was charged with both assault and Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty. His defense against the obstruction charge was simple: Article 95 of the Penal Code punishes an assault "against a public official." He argued that he had assaulted C, a private citizen, not Bailiff B, the public official. Therefore, he could not be guilty of this specific crime.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: An Attack on the Assistant is an Attack on the Duty

The Supreme Court rejected this defense and upheld the conviction for obstruction. The Court's decision, though brief, established a clear and powerful legal principle. It held:

The crime of Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty under Article 95, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code requires that assault or intimidation sufficient to obstruct the performance of a public duty be carried out while a public official is performing their duties. However, the said assault or intimidation is not necessarily limited to cases where it is directly applied to the body of the said public official, but also applies to cases where it is directed at an assistant who is acting under the command of the said public official, as his/her hands and feet, and is involved in a manner inextricably linked to the performance of the duty.

Applying this rule to the facts, the Court found that the defendant's assault on C—who was acting as an assistant under Bailiff B's direct orders to move property—was an assault that obstructed Bailiff B's duty, even though it was not directed at the bailiff's own body.

Analysis: The Concept of "Indirect Assault" and Its Controversies

This ruling is the first Supreme Court precedent to explicitly recognize that an assault on a non-official assistant can constitute the crime of obstructing a public duty. It is a key example of the legal concept of "indirect assault" in this context.

- Protecting the Function, Not Just the Person: The core rationale behind this principle is that the law protects the function of the public duty, not merely the physical safety of the individual official. Since the assistant is acting as an indispensable instrument for the performance of that duty, an attack on the assistant is functionally an attack on the duty itself.

- A Contentious Interpretation: This broad interpretation of "assault" has been a subject of significant academic criticism in Japan. Critics argue that it stretches the statutory language—which requires an assault "against him/her" (kore ni taishite, i.e., against the public official)—too far, potentially violating the principle of legality (no crime without a clear statute). They contend that it blurs the line between "assault or intimidation" (bōkō matawa kyōhaku), the specific means required by Article 95, and the broader concept of "force or influence" (iriki), which the legislature used in other obstruction statutes but deliberately omitted from this one.

- The Court's Pragmatic Focus on Effect: While theoretically complex, the Court's approach is highly pragmatic. It recognizes the reality that stopping the bailiff's "hands and feet" is one of the most effective ways to stop the bailiff himself. The decision text highlights the result of the defendant's action: the bailiff was "forced to temporarily halt the execution." The Court appears to work backward from the undeniable fact that the public duty was obstructed to conclude that the means used to achieve that obstruction must fit the statutory definition of assault.

A Modern Postscript: A New Law for a Specific Problem

It is important to note that the Japanese legal landscape has evolved since 1966.

- In 2011, as part of a broader reform of laws related to compulsory execution, a new, more specific crime was established: Obstruction of Acts of Compulsory Execution (Penal Code Art. 96-3).

- This new statute punishes anyone who uses "deception or force/influence" (gikei matawa iriki) to obstruct an act of compulsory execution, such as an eviction.

- Crucially, this new law does not require that the target of the force be a public official.

- Therefore, if a case with identical facts were to occur today, it would likely be prosecuted under this new, more fitting statute, which perfectly covers the act of assaulting a mover to stop an eviction. This demonstrates how the law often evolves to codify judicial interpretations that, while effective, may have stretched the boundaries of older statutes.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1966 decision remains a vital precedent for understanding the scope of the crime of Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty. It established that an attack on a private citizen who is acting as an indispensable instrument of a public official is legally equivalent to an attack on the public duty itself. The ruling prioritizes the protection of the state's ability to function over a hyper-literal reading of the statute, focusing on the real-world effect of a defendant's actions rather than the precise target of their violence. While the decision was controversial, its practical outcome has since been reflected in more specific legislation, showing the ongoing dialogue between the judiciary and the legislature in shaping the contours of criminal law.