The Long Arm of the Law: How Japan's High Court Expanded the Scope of Bribery

The crime of bribery is commonly understood as paying a public official to influence a decision they directly control. But what if the official has no direct authority over the matter in question? If a person pays a police officer assigned to Precinct A to influence an investigation happening across town in Precinct B, can this still be a criminal bribe? How far does an official's "duty" extend? Does it follow their specific job description, or does it follow their uniform and title wherever they go?

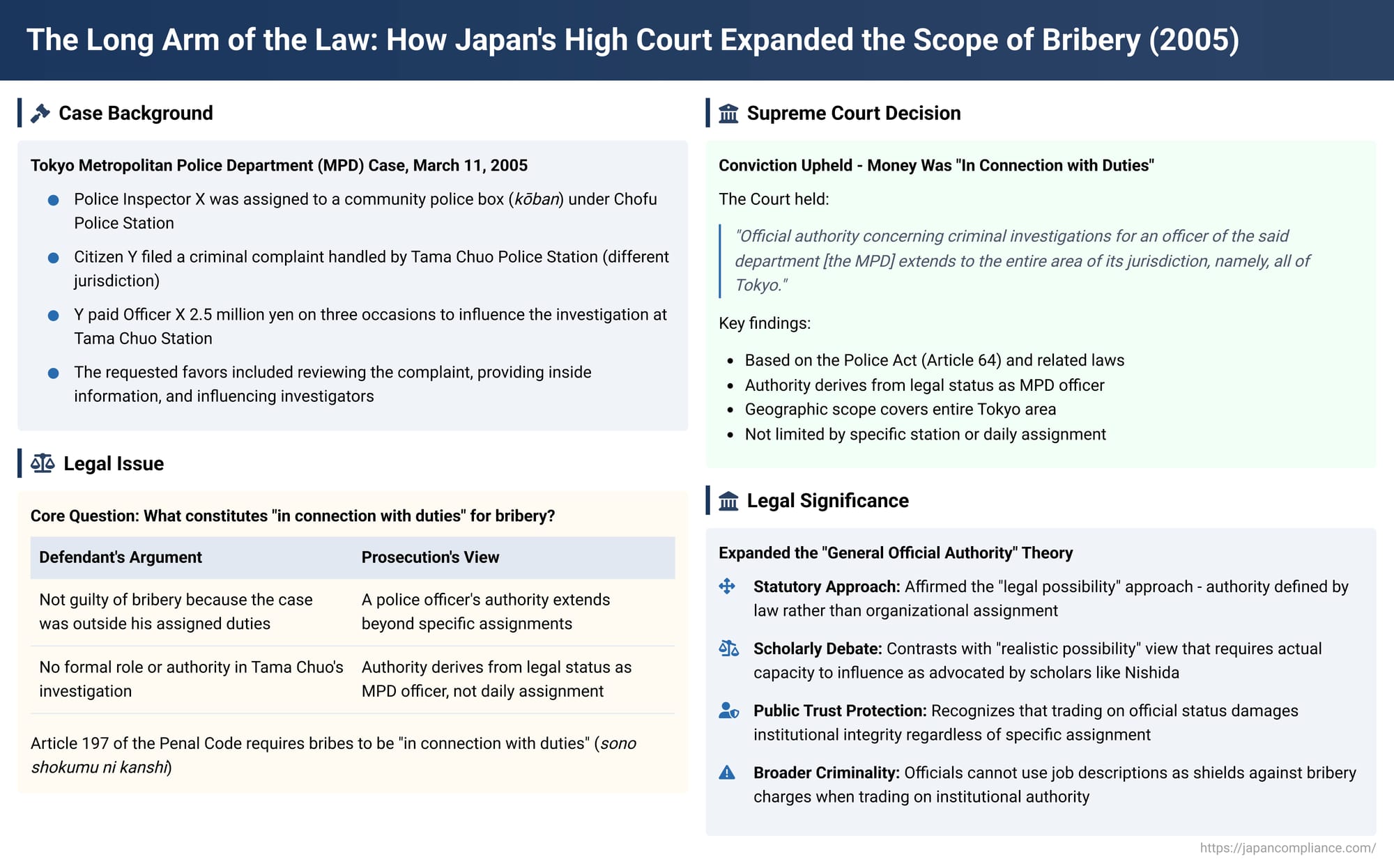

This critical question of the scope of an official's authority was at the center of a key decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 11, 2005. The case, involving a police officer who took money in connection with an investigation at another station, affirmed a broad, legally-based definition of a public official's duties for the purposes of bribery law.

The Facts: The Cop, the Complainant, and the Other Police Station

The case involved a police inspector (a keibuho rank) with the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), whom we will call X.

- The Defendant's Position: X was assigned to a local community police box (kōban) within the jurisdiction of the Chofu Police Station, where he worked in the Community Police Affairs Division.

- The Criminal Complaint: A citizen, Y, had filed a criminal complaint concerning a case of alleged false entries in a notarial deed. This complaint was filed with, and was being handled by, the Tama Chuo Police Station—a completely different station from the one where X worked.

- The Bribe: Y paid Defendant X a total of 2.5 million yen on three separate occasions.

- The Requested Favors: In exchange for the money, Y sought "favorable and convenient treatment" from X regarding the case being handled by the Tama Chuo station. This treatment included:

- X reviewing the criminal complaint and offering advice.

- X providing Y with inside information about the investigation.

- X using his position to influence the investigators at the Tama Chuo station who were actually handling the case.

The Legal Defense: "It Wasn't My Job"

The defendant's core argument was that he could not be guilty of bribery because the investigation was outside his scope of official duties. He was a community police officer at the Chofu station; he had no formal role, authority, or involvement in a criminal investigation being conducted by the criminal division of the Tama Chuo station. Therefore, he argued, the money he received was not "in connection with his duties" (sono shokumu ni kanshi), a required element for the crime of bribery under Article 197 of the Penal Code.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: A Force-Wide Definition of Duty

The Supreme Court rejected this defense and upheld the bribery conviction. The Court's reasoning was concise but powerful, looking beyond the officer's specific daily assignment to the general laws governing his position.

- The Court cited Japan's Police Act (specifically Article 64) and other related laws as the basis for its decision.

- It ruled that based on these statutes, the "official authority concerning criminal investigations for an officer of the said department [the MPD] extends to the entire area of its jurisdiction, namely, all of Tokyo."

- Therefore, the Court concluded, even though Defendant X was assigned to a police box in Chofu and was not involved in the Tama Chuo investigation, his act of accepting money for favors related to that investigation was indeed an act "in connection with his duties."

Analysis: The "General Official Authority" Theory and Its Limits

This decision is a key example of the "general official authority" (ippan-teki shokumu kengen) theory in Japanese bribery law. This long-standing doctrine holds that a bribe is illegal if it relates not just to an official's specific, currently assigned tasks, but to any matter that falls within their general scope of authority as a public servant.

- How Broad is "General Authority"?: The 2005 ruling is significant because it appears to define this general authority in very broad terms.

- Previous Cases: Earlier Supreme Court precedents had often limited an official's "general authority" to their own section (kakari) or division (ka). This was typically based on the idea that the official could realistically be reassigned to other tasks within that unit, giving them potential influence over its affairs. This is often called the "realistic possibility" approach.

- The 2005 Shift: This decision, by contrast, grounded the officer's authority not in his specific assignment or the possibility of reassignment, but in the overarching statute that grants all MPD officers investigative authority throughout Tokyo. This is known as the "legal possibility" approach.

- A Scholarly Debate: This expansion has been the subject of considerable academic debate.

- The Critique: The prevailing scholarly view, often associated with Professor Norio Nishida, argues that the Court's approach is too broad. This view contends that for a bribe to be illegal, the official must have a "realistic possibility" of actually influencing the matter. Without this concrete connection, the link to duty is purely theoretical, and the law risks over-criminalization. For example, under a strict "legal possibility" reading, a tax official in Tokyo could theoretically be bribed for a case in Sapporo, as they are both part of the same national tax agency, a result many find absurd.

- The Counter-Argument: Those who support the Court's decision argue that it aligns better with the public's perception and the nature of bribery law's protected interest. The public generally does not distinguish between the jurisdictions of different police stations within the same city; they see a police officer as a police officer. Therefore, when any officer trades on their official status, it damages the public's trust in the fairness of the entire institution.

- What About the Specific Favors Requested?: Even if the general subject matter was within the officer's purview, were the specific acts requested (giving advice, leaking information, influencing others) part of his "duties"? Japanese law also recognizes that taking a bribe for acts "closely related to official duties" (shokumu missetsu kanren kōi) is illegal. Legal analysis suggests that the requested favors would likely qualify.

- Giving advice to a citizen about a criminal complaint falls within the general duties of a community police officer.

- Leaking confidential information obtained by virtue of one's official position is a breach of the duty to maintain secrecy, making it closely related to official duties.

- Influencing other officers, while more complex, could be achieved through official channels (e.g., passing along information to his own superiors, who could then communicate with the other station), thus creating a link to his official functions.

Conclusion

The 2005 Supreme Court decision affirmed a broad and potent interpretation of a public official's "duties" for the purpose of bribery law. By grounding a police officer's authority in the full legal scope of their parent organization rather than their specific daily assignment, the ruling makes it clear that an official cannot use their particular job description as a shield. The case serves as a stern warning that the law may view an official's duties far more broadly than their organizational chart might suggest. Attempting to trade on one's official status and uniform for any matter within the organization's legal purview can be deemed a criminal act of bribery.