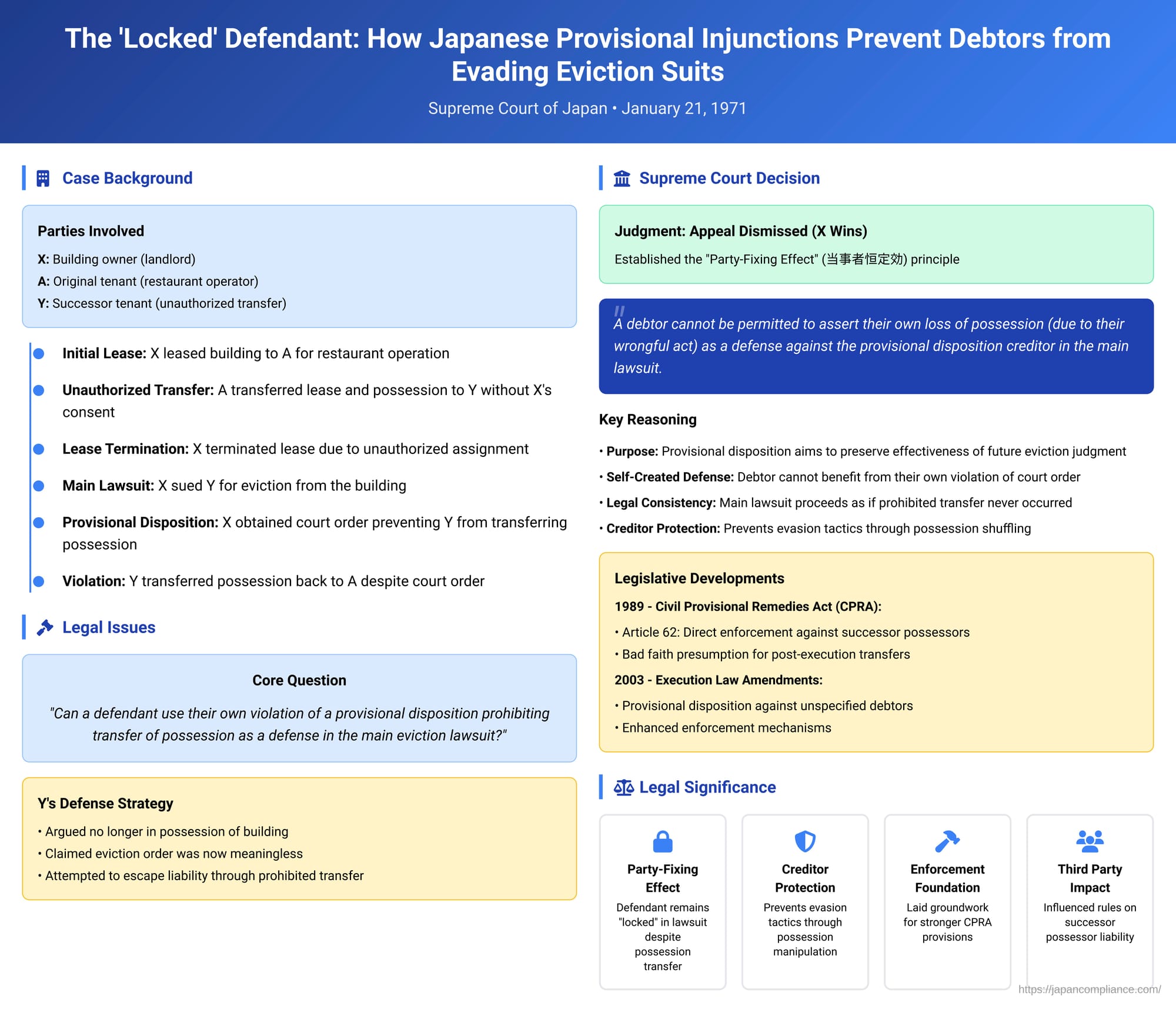

The 'Locked' Defendant: How Japanese Provisional Injunctions Prevent Debtors from Evading Eviction Suits by Transferring Possession

Date of Supreme Court Decision: January 21, 1971

In legal disputes over the possession of real property, a common tactic by a defendant facing eviction might be to transfer possession to a third party, thereby attempting to render the ongoing lawsuit against them moot or to complicate future enforcement. Japanese law, however, provides a powerful interim remedy known as a "provisional disposition prohibiting transfer of possession" (占有移転禁止の仮処分 - sen'yū iten kinshi no karishobun). A landmark 1971 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Showa 43 (O) No. 20) clarified a crucial aspect of this injunction's effect: even if the defendant violates the order and transfers possession, they cannot use that transfer as a shield against the plaintiff's main lawsuit. This principle, established under the old Code of Civil Procedure, laid the groundwork for even stronger protections later codified in the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA).

The Factual Scenario: A Restaurant Lease, Unauthorized Transfer, and an Injunction

The case involved X, the owner of a building, who had leased it to A. A operated a restaurant in the premises. Subsequently, Y took over the restaurant business from A and, along with it, the leasehold right to the building, thereby coming into possession.

X, the building owner, did not consent to this assignment of the lease by A to Y. Asserting that this was an unauthorized transfer, X notified A of the termination of the lease agreement. X then filed a lawsuit (the "main lawsuit") against Y, seeking Y's eviction from the building.

The Provisional Disposition:

While this main eviction lawsuit against Y was pending, X applied for and obtained a provisional disposition from the court. This order was specifically designed to prevent Y from further transferring possession of the building and to preserve the effectiveness of any future eviction judgment X might obtain against Y. The terms of this particular provisional disposition involved:

- Removing Y from possession of the building.

- Placing the building under the custody of a court bailiff (執行吏 - shikkōri, the precursor to the modern 執行官 - shikkōkan).

- Prohibiting Y from transferring possession to any third party.

- Simultaneously allowing Y to continue using the premises under these conditions.

This provisional disposition was duly executed.

Despite this court order being in effect, Y later handed over possession of the building to A (the original tenant) and thereafter ceased to be in actual physical possession of the property. (It was also noted that X subsequently obtained a second provisional disposition, this time against A, which involved placing the property in bailiff's custody but allowing X, the creditor/owner, to use it. This second order eventually led to X regaining actual possession.)

The Tokyo District Court, in the main lawsuit, ruled in favor of X and ordered Y to vacate the premises. Y appealed, but the Tokyo High Court upheld the first instance judgment. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court, a key argument being that Y no longer possessed the building and therefore could not be ordered to vacate it.

The Supreme Court's 1971 Ruling: Debtor Remains "Fixed" as Defendant

The Supreme Court, in its decision of January 21, 1971, dismissed Y's appeal.

Core Holding: The Court established a critical principle regarding the effect of a provisional disposition prohibiting the transfer of possession:

- Such an injunction is specifically aimed at preventing the debtor (the party subject to the injunction, like Y) from transferring possession of the property to someone else. Its purpose is to preserve the ability of the creditor (X) to effectively enforce a final judgment for the delivery or vacation of that property which might be obtained in the main lawsuit.

- If the debtor, after the provisional disposition has been executed against them, violates the order by transferring possession of the property to a third party, that debtor cannot be permitted to assert their own loss of possession (due to their wrongful act) as a defense against the provisional disposition creditor in the main lawsuit.

- Therefore, the creditor is entitled to continue pursuing the main lawsuit against the original debtor named in the provisional disposition, without needing to take into account the debtor's subsequent (and unlawful) transfer of possession.

Application to the Case:

In this instance, Y's act of transferring possession of the building to A was a clear violation of the provisional disposition order that Y was subject to. Consequently, Y (the provisional disposition debtor) was legally barred from arguing to X (the provisional disposition creditor) that Y had lost possession. The High Court was therefore correct in treating Y as still being the legal possessor for the purposes of the eviction lawsuit and in ordering Y to vacate the building.

This ruling effectively created a "party-fixing effect" (当事者恒定効 - tōjisha kōteikō) for this type of provisional disposition. It meant that the defendant in the main lawsuit remained "fixed," and the suit could proceed against them as if the prohibited transfer of possession had not occurred, at least as far as the relationship between the creditor and that specific debtor was concerned.

Beyond the 1971 Ruling: Legislative Enhancements to the Injunction's Power

The 1971 Supreme Court decision was a significant step in protecting creditors, but it was decided under the old Code of Civil Procedure, which lacked detailed provisions on the extended effects of such injunctions, particularly against third-party transferees. Legal commentary and practice recognized certain remaining challenges:

The Problem Under the Old Law:

While the 1971 ruling prevented the original debtor from using their own violation as a defense, the question of how to enforce an eviction judgment (obtained against that original debtor) against the new person actually in possession (e.g., A in this case, or any subsequent transferee) was more complex. The prevailing view was that the creditor would need to obtain a "successor execution writ" (承継執行文 - shōkei shikkōbun) against the new possessor. This required the creditor to prove the fact of the transfer of possession, a burden which could be difficult and which opened the door to potential obstruction tactics by debtors who might repeatedly transfer possession to different individuals.

Recognizing these difficulties, Japanese law was subsequently strengthened through legislative reforms, primarily with the enactment of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA) in 1989 (effective 1991) and further amendments to execution laws in 2003. These reforms significantly enhanced the power and effectiveness of provisional dispositions prohibiting the transfer of possession:

1. The Civil Provisional Remedies Act (1989):

- CPRA Article 62, Paragraph 1: This provision was a major step forward. It explicitly clarified that if a provisional disposition prohibiting the transfer of possession (of a specified type, including those where the debtor is allowed continued use under bailiff custody, as in the Hoppo Journal case facts) has been executed, the creditor can, based on their final judgment in the main lawsuit (obtained against the original debtor), directly enforce the delivery or vacation of the property against any person who succeeded to the debtor's possession after the execution of the provisional disposition.

- More controversially, but aimed at tackling sophisticated obstruction, this article also extended enforceability to non-succeeding possessors (i.e., those who didn't directly receive possession from the debtor but took it through other means) if they were in bad faith regarding the prior execution of the provisional disposition (meaning they knew about the injunction when they took possession). The rationale was that such persons rarely have a legitimate right to possess and allowing enforcement against them was necessary.

- CPRA Article 62, Paragraph 2 (Presumption of Bad Faith): To further assist the creditor, this paragraph introduced a presumption. If the execution of the provisional disposition was publicly notified (e.g., by a bailiff posting an official notice on the property, as permitted under CPRA Article 25-2, Paragraph 1, Item (ii)), any person who takes possession of the property after such execution and notification is presumed to have done so in bad faith. This effectively shifts the burden of proof to the new possessor to demonstrate their good faith and unawareness of the injunction.

- Practical Effect: These provisions significantly eased the creditor's burden. Generally, the creditor now only needs to prove that the provisional disposition was executed and that the current occupant took possession thereafter. This typically suffices for obtaining the necessary execution writ against the current occupant.

- Protection of Third-Party Rights: It's important to note that these provisions do not trample legitimate third-party rights. A new possessor who is in good faith (and not a successor to the debtor's possession in the context of the injunction) or who has an independent right to possess the property that is valid against the provisional disposition creditor can still challenge the enforcement. They can do so, for example, by filing an objection to the issuance of an execution writ (under Article 32 of the Civil Execution Act) or a lawsuit objecting to the execution writ itself (under Article 34 of the Civil Execution Act). CPRA Article 63 specifically affirms the availability of such objection procedures.

2. The 2003 Amendments to Civil Execution and Provisional Remedy Laws – Further Bolstering Effectiveness:

Despite the improvements in the 1989 CPRA, sophisticated debtors could still attempt to frustrate enforcement by rapidly and repeatedly changing the person in actual physical possession of a property, making it a challenging cat-and-mouse game for creditors to identify and serve the correct party. The 2003 legal reforms introduced further measures to enhance the effectiveness of eviction and delivery executions:

- Provisional Disposition Against Unspecified Debtor (CPRA Art. 25-2): This allows a court, under certain conditions, to issue a provisional disposition prohibiting the transfer of possession of real property without specifying the debtor by name in the initial order. The order is directed against the property itself, and the actual debtor (the person whose possession is to be constrained) is identified by the bailiff at the time of execution. This is particularly useful when the creditor knows the property is being illicitly occupied but is unsure of the exact identity of the current occupant(s). The rationale is that since an initial hearing of the debtor is not always mandatory for such provisional dispositions (and execution can occur before service of the order on the debtor), identifying the debtor at the execution stage and then affording them an opportunity to object provides sufficient procedural protection.

- Successor Execution Writ Against Unspecified Possessor (Civil Execution Act Art. 27, Paragraph 3, Item (i)): Complementing the above, if a provisional disposition prohibiting the transfer of possession of real property has been executed (especially one issued against an unspecified debtor or one with public notification), an execution writ based on the final judgment in the main suit can, under certain conditions, be issued without specifying the name of the current possessor. This allows for direct enforcement against whoever is found on the premises at the time of actual execution, provided they took possession after the provisional order's execution (and are therefore presumed to be in bad faith). Again, such possessors have means to object if they have legitimate rights.

- "Notice of Demand for Vacating" with Party-Fixing Effect (Civil Execution Act Art. 168-2): This introduced a new, powerful pre-eviction step. A bailiff, prior to carrying out a forcible eviction based on a judgment, can serve a formal "notice of demand for vacating" on the occupant. This notice itself has the legal effect of prohibiting subsequent transfers of possession. If possession changes after this notice has been served and publicized, the original eviction judgment can be enforced against the new possessor without the creditor needing to obtain a separate successor execution writ. This is a very effective tool against last-minute attempts to obstruct enforcement by swapping occupants.

Unresolved Interpretive Issues:

Legal commentary points out that even with these legislative advancements, some complex interpretive issues remain, such as the precise extent to which the res judicata (claim preclusion) effect of the final judgment in the main lawsuit (obtained against the original debtor) applies to a new possessor against whom execution is sought. The conditions under which a new possessor can or should intervene in or formally succeed to the main lawsuit also continue to be debated.

Related Type of Injunction – Disposition Prohibition:

It's worth noting that the principles discussed here primarily concern injunctions against the transfer of possession. A related but distinct type is a "provisional disposition prohibiting disposition" (処分禁止の仮処分 - shobun kinshi no karishobun), which targets acts like selling, mortgaging, or otherwise legally encumbering a property (rather than just changing who physically occupies it). A Supreme Court case from a similar era (Showa 45.9.8) also affirmed a "party-fixing effect" for such injunctions concerning buildings (e.g., to preserve a claim for building removal and land vacation). It held that a third party acquiring the building in violation of such an injunction could not assert their acquired rights against the provisional disposition creditor. However, it also noted that this did not mean the third party's acquisition was entirely nullified for all purposes against all people; its effect was relative to the creditor. The CPRA (in Article 64) now also provides specific rules to clarify execution against successors in title when a disposition prohibition provisional order has been issued.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1971 Supreme Court decision in the "restaurant lease" case was a foundational ruling under the old Code of Civil Procedure. It established the crucial "party-fixing effect" of a provisional disposition prohibiting the transfer of possession, preventing a debtor from derailing an eviction lawsuit by simply handing over the keys to someone else in violation of a court order. This principle ensured that the creditor could continue their main lawsuit against the original party named in the injunction.

More importantly, this judicial stance paved the way for significant legislative developments. The subsequent enactment of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act in 1989, and the further reforms to civil execution laws in 2003, built upon and greatly strengthened this foundation. These laws have provided creditors in Japan with increasingly robust and sophisticated tools to combat bad-faith obstruction and to ensure that judgments for the recovery of property can be effectively enforced, even when debtors attempt to frustrate the process by illicitly transferring possession to third parties. The evolution of this area of law reflects a continuous legislative and judicial effort to strike a fair balance between the need for effective provisional protection for claimants and the procedural rights of both debtors and any third parties who might become involved.