The Lingering Shadow of a Flawed Vote: Challenging Financial Statement Approvals in Japan

Case: Action for Annulment of a Shareholders' Meeting Resolution

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of June 7, 1983

Case Number: (O) No. 17 of 1980

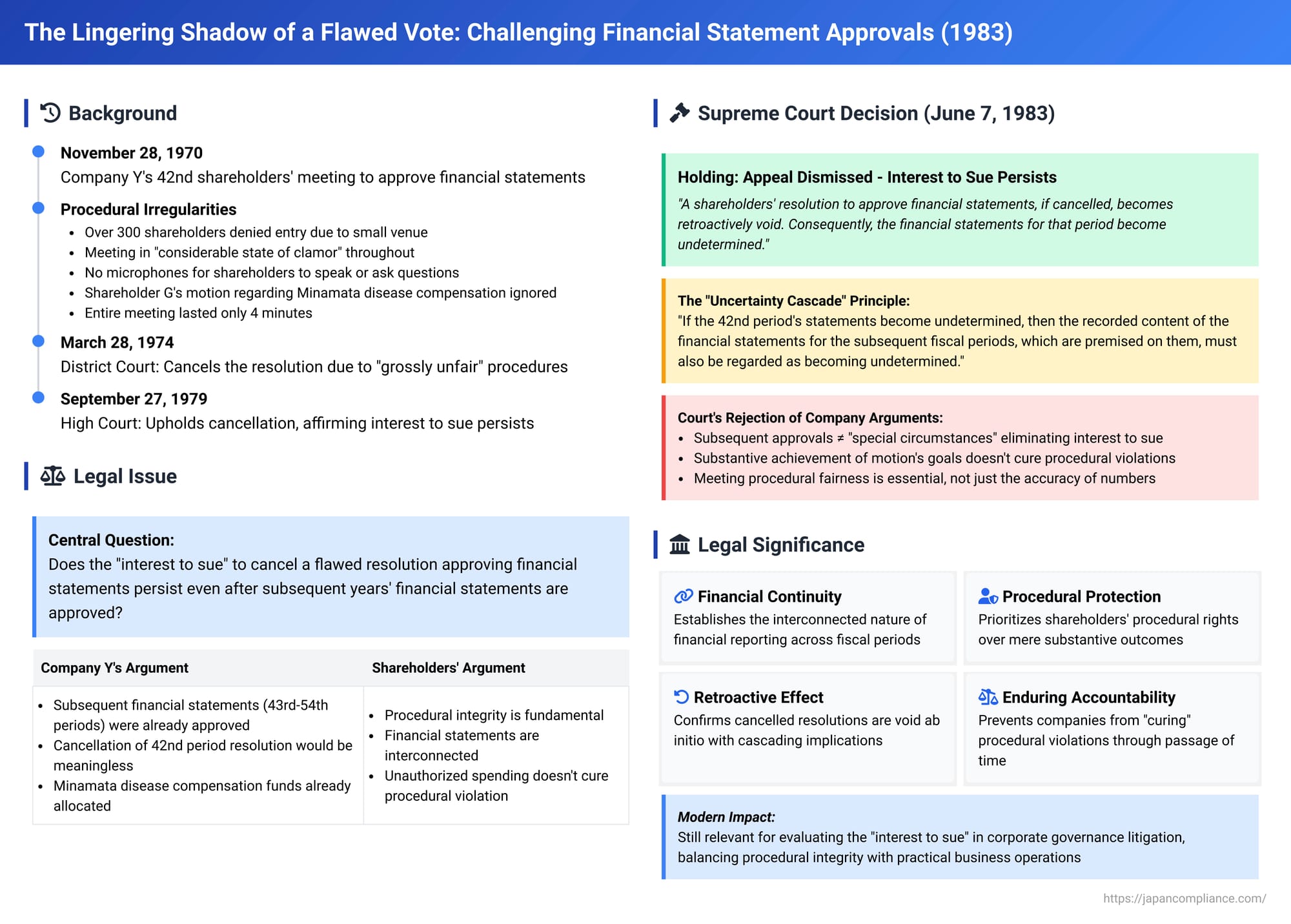

What happens when a company's annual financial statements are approved at a chaotic and procedurally flawed shareholders' meeting? Can shareholders still challenge that approval years later, even after subsequent financial statements for later years have been seemingly rubber-stamped? This question was at the heart of a significant decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on June 7, 1983. The Court ultimately affirmed that the "interest to sue" to cancel such a flawed approval is not easily extinguished, especially given the interconnected nature of financial reporting.

The Tumultuous 42nd Shareholders' Meeting: Facts of the Case

On November 28, 1970, Company Y held its 42nd ordinary general shareholders' meeting. The agenda included the approval of the business report, balance sheet, profit and loss statement, and the proposal for the appropriation of profits for the 42nd fiscal period, which spanned from April 1, 1970, to September 30, 1970 (referred to as "the Resolution").

The meeting, however, was far from ordinary. According to the plaintiffs, G and 26 other shareholders of Company Y:

- Overcrowding and Exclusion: The chosen venue, a hall at the Osaka Kosei Nenkin Kaikan, was too small for the number of shareholders who attended. As a result, over 300 shareholders were denied entry and could not participate in the meeting or exercise their voting rights.

- Chaotic Atmosphere: The meeting was described as being in a "considerable state of clamor" from the moment proposals were introduced until the resolutions were purportedly passed.

- Lack of Shareholder Voice: Crucially, there were no microphones or other means available for shareholders to make themselves heard or to pose questions.

- Ignored Motion: One of the plaintiffs, G, attempted to introduce a revised motion. He went near the stage where the chairman and company officials were seated, shouted that he had a revised motion, and waved a flyer detailing his proposal. This proposal included setting aside specific reserves for Minamata disease compensation and related countermeasures. Despite G's efforts, his motion was entirely ignored by the chairman.

- A Four-Minute Meeting: The entire proceeding, from the declaration of opening to the announcement of the meeting's closure, lasted a mere four minutes. The chairman declared that the agenda items, including the approval of the financial statements, were approved by a majority.

Believing the resolution method to be grossly unfair due to these significant procedural irregularities, G and the other shareholders filed a lawsuit to cancel the Resolution approving the 42nd period's financial statements and profit appropriation.

Lower Court Battles: Interest to Sue Upheld

The court of first instance (Osaka District Court, judgment dated March 28, 1974) sided with the plaintiffs. It found that Company Y had failed in its duty to ensure all shareholders had an opportunity to exercise their voting rights, and that ignoring G's attempted revised motion rendered the resolution method "grossly unfair." Consequently, the court cancelled the Resolution. The court also noted that the "interest to sue" (the legal standing or practical benefit required to maintain a lawsuit) would not disappear even if the substantive aims of G's ignored motion (like the Minamata disease compensation reserves) were later achieved through other means.

Company Y appealed, but the appellate court (Osaka High Court, judgment dated September 27, 1979) upheld the District Court's decision and dismissed the appeal. The High Court specifically affirmed the existence of an interest to sue. It reasoned that the appropriation of profits approved in the 42nd fiscal period would inevitably affect the financial statements of subsequent periods. This continuing impact, the court suggested, could not be entirely rectified or nullified simply because financial statements for later periods were subsequently approved, thus preserving the plaintiffs' interest in challenging the original flawed approval. Company Y then brought the case before the Supreme Court.

The Company's Argument Before the Supreme Court

Company Y's primary argument to the Supreme Court was that the lawsuit had lost its "interest to sue." They contended that even if the 1970 Resolution approving the 42nd period's financials were to be cancelled, it would be a meaningless act. Why? Because, in the intervening years, the financial statements and profit appropriations for numerous subsequent fiscal periods (specifically, the 43rd through the 54th periods) had already been approved at their respective annual general meetings and were considered settled. Therefore, cancelling a resolution related to a distant past period would have no practical effect on the company's current financial standing or its approved accounts, rendering the lawsuit moot.

Furthermore, Company Y argued that the substantive issue underlying G's ignored motion—the creation of reserves for Minamata disease—had been addressed. The company claimed that funds exceeding the amounts G had proposed for reserves had already been spent on compensation and countermeasures for Minamata disease. This, they asserted, meant the objective of the motion was achieved, thereby healing the procedural defect of ignoring it and nullifying the interest to sue.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Appeal Dismissed

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of June 7, 1983, dismissed Company Y's appeal, affirming the decisions of the lower courts.

Reasoning of the Apex Court

The Supreme Court meticulously laid out its reasoning:

- Nature of Formative Lawsuits and Interest to Sue: The Court began by reiterating a general principle: a "formative lawsuit" (a suit seeking to change a legal status, such as one to cancel a shareholder resolution) is permitted only where prescribed by law. If the legal requirements for such a suit are met, there is usually an "interest to sue." However, this interest can be lost due to subsequent changes in circumstances.

- Retroactive Effect of Cancellation: The Court then focused on the specific nature of the lawsuit: a challenge to a resolution approving financial statements (business report, balance sheet, profit and loss statement, and profit appropriation plan for the 42nd period) due to procedural flaws. If a judgment cancelling this Resolution becomes final and binding, the Resolution is rendered retroactively void – meaning it is treated as invalid from the very beginning.

- As a consequence, the financial statements for the 42nd period would lack shareholder approval.

- Furthermore, any appropriation of profits made based on this voided resolution would also lose its legal effect.

- Legally, this would necessitate a new resolution by the shareholders to properly approve the financial statements for that period.

- Interest to Sue Persists Barring Special Circumstances: Based on the retroactive invalidity, the Court concluded that the interest in pursuing the cancellation lawsuit is not lost, unless special circumstances exist, such as a subsequent valid re-resolution having already been passed concerning the same financial statements for the 42nd period.

- Approval of Subsequent Financials is Not a "Special Circumstance": The Court directly addressed Company Y's main argument. The company claimed that because the financial statements for the 43rd to 54th periods had been approved and finalized, the cancellation of the 42nd period's resolution would have no impact and thus the lawsuit lacked interest. The Supreme Court disagreed.

It reasoned that if a shareholders' resolution approving financial statements is cancelled due to procedural violations (even if the content of those statements is not alleged to be illegal or improper), that resolution becomes retroactively void. This means the financial statements for that period become "unsettled" or "undetermined" (mikakutei).

Crucially, financial statements are built upon the foundation of previous periods. The closing figures of one year become the opening figures for the next. Therefore, if the 42nd period's statements become undetermined, then "the recorded content of the financial statements for the subsequent fiscal periods, which are premised on them, must also be regarded as becoming undetermined."

As a result, Company Y would be obligated to hold a new shareholders' meeting to properly approve the financial statements for the 42nd period. The mere fact that subsequent, separate fiscal periods' statements were approved does not constitute a "special circumstance" that negates this obligation or the interest to sue regarding the original flawed approval. - Substantive Achievement of a Motion Doesn't Cure Procedural Flaws: The Court also dismissed Company Y's argument that the interest to sue was lost because the objective of G's ignored motion (Minamata disease compensation) had already been achieved through company expenditures. The Court clarified that the lawsuit was based on procedural flaws in the shareholders' meeting – specifically, the exclusion of shareholders and the ignoring of a shareholder's motion. The subsequent substantive realization of the content of that motion does not heal these fundamental procedural defects in the conduct of the meeting itself. Therefore, this did not constitute a "special circumstance" that would eliminate the interest to sue.

Finding no such special circumstances, the Court concluded that the interest to sue remained intact and upheld the lower court's decision.

Analysis and Implications: The Enduring Importance of Procedural Integrity

This 1983 Supreme Court judgment carries significant implications for corporate governance and shareholder rights in Japan.

- Robust Protection for Procedural Rights: The decision strongly affirms that the procedural integrity of shareholders' meetings, especially when approving crucial documents like financial statements, is paramount. Shareholders have a right to a fair process, and the courts will protect that right.

- The "Uncertainty Cascade" in Financial Reporting: The core of the Court's reasoning regarding the interconnectedness of financial statements is vital. The idea that voiding one year's approval makes those financials "undetermined" and, by extension, casts a shadow of uncertainty over subsequent years' figures that rely on them, underscores the continuous nature of accounting.

This "unravelling effect" means that companies cannot simply assume that subsequent approvals will cleanse earlier procedural sins. The Court essentially stated that the financial narrative of a company is a chain, and a broken link early on can compromise the integrity of what follows. While the judgment uses the term "undetermined," legal commentators have debated the precise scope of this – whether it means subsequent statements are entirely void, partially flawed, or simply require the underlying prior-period figures to be re-certified. The prevailing interpretation of the judgment is that the affected prior-period financials must be re-approved, thereby rectifying the basis for subsequent statements. - Retroactive Invalidation is Key: The Court's reliance on the principle that cancellation of a resolution has retroactive effect is fundamental to its conclusion. If the approval was flawed from the start, it's as if it never happened. This aligns with general principles of Japanese civil law and is now explicitly stated in Article 839 of the Companies Act concerning the effect of judgments annulling shareholder resolutions.

- Distinction from Other Types of Resolutions: This case differs from scenarios involving, for example, the appointment of directors where, if the directors have already served their terms and retired, the interest to sue for cancelling their appointment resolution might be lost (barring other special circumstances, as seen in a 1970 Supreme Court case). Financial statements have an ongoing, cumulative relevance to the company's legal and financial status that may not be so easily time-limited.

- Substantive Correctness vs. Procedural Fairness: The Supreme Court emphasized that even if the content of the financial statements for the 42nd period was not itself challenged as being illegal or improper, the procedural flaws in how the approval was obtained were sufficient to warrant cancellation. This highlights that shareholder approval is not just a rubber stamp for technically correct numbers; it is a fundamental exercise of shareholder governance and oversight, which demands a fair process.

However, some legal commentary has posed a nuanced question: if the financial statements for the flawed period were, in fact, substantively accurate according to generally accepted accounting principles, does their procedurally flawed approval truly render subsequent, correctly approved financial statements "undetermined"? Modern accounting standards often provide mechanisms for correcting errors or omissions from prior periods by restating them, without necessarily invalidating all intervening financial reports. This suggests that the rationale for maintaining the interest to sue in such cases might also rest heavily on upholding the sanctity of the shareholder approval process itself, beyond just the numerical accuracy. - No Easy Escape Hatch: The ruling makes it clear that achieving the substantive goal of an improperly ignored shareholder motion does not retroactively cure the procedural defect of ignoring it in the first place. The right to participate and be heard at a shareholders' meeting is distinct from the eventual outcome of a particular proposal.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1983 decision serves as a powerful reminder that the approval of financial statements is a cornerstone of corporate accountability, demanding scrupulous adherence to procedural fairness at shareholders' meetings. The judgment establishes that the chain of financial reporting is not easily broken; a flawed approval in one period can cast a long shadow, generally preserving a shareholder's right to challenge that defect even if subsequent periods' financials have been approved. The "interest to sue" remains because the very foundation of those subsequent approvals is potentially compromised until the initial flaw is addressed through a proper, lawful re-approval process. This underscores the judiciary's commitment to ensuring that shareholder democracy and oversight are not mere formalities but are backed by enforceable rights to a fair and transparent process.