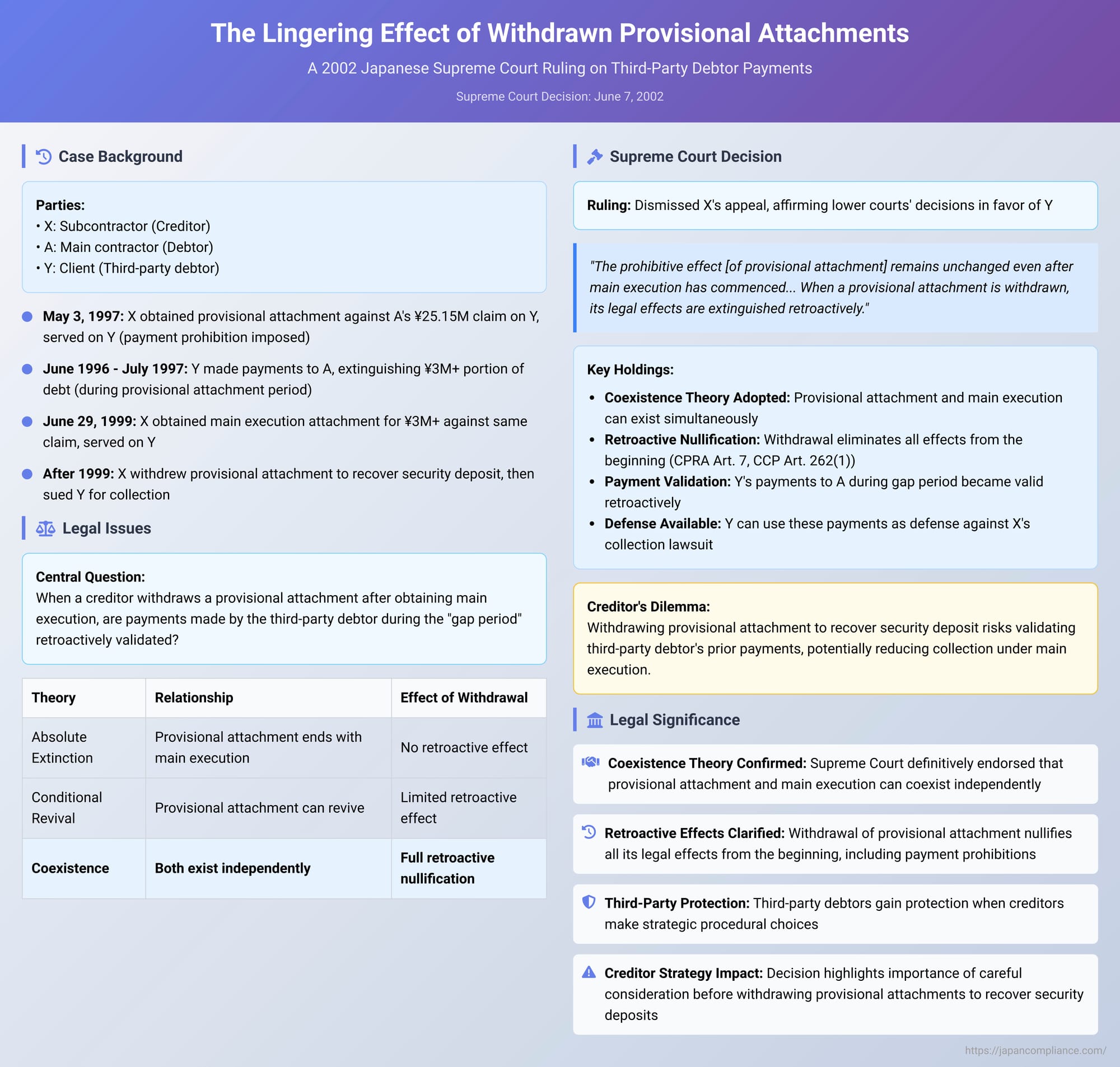

The Lingering Effect of Withdrawn Provisional Attachments: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Third-Party Debtor Payments

Date of Supreme Court Decision: June 7, 2002

In the complex world of debt recovery, a "provisional attachment" (仮差押え - karisashiosae) is a crucial interim measure in Japanese law that allows a creditor to secure a debtor's assets pending a final judgment. When this targets a monetary claim owed by a third party to the debtor, it imposes a "prohibition on payment" (弁済禁止効 - bensai kinshi kō) on that third party. But what happens if the creditor, after obtaining this provisional attachment and later initiating "main execution" (本執行 - honshikkō – a full attachment based on a judgment), decides to withdraw the initial provisional attachment, perhaps to recover the security they deposited? A 2002 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Heisei 13 (Ju) No. 1662) addressed the significant consequences of such a withdrawal, particularly concerning payments made by the third-party debtor during the period when only the provisional attachment was in effect.

The Factual Timeline: A Construction Claim, Provisional Attachment, Main Execution, and a Crucial Withdrawal

The dispute involved X, a subcontractor (the creditor); A, the main contractor (the original debtor); and Y, the client who owed A money for construction work (the third-party debtor).

- The Underlying Debt and Provisional Attachment: X held a subcontracting claim of over ¥5.77 million against A. To secure this claim, X obtained a provisional attachment order against a ¥25.15 million claim that A had against Y (for the main construction project), up to the amount of X's claim against A.

- May 3, 1997: This provisional attachment order was served on Y, the third-party debtor. Under Article 50, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA), this service prohibited Y from making payments on the attached portion of its debt to A, for the benefit of X.

- Transition to Main Execution: Subsequently, X obtained an enforceable title (such as a final judgment) against A for a portion of its claim, amounting to over ¥3 million (referred to as the "Honken Saiken" – the Claim in Question). X then proceeded to "main execution" by obtaining a full attachment order (差押命令 - sashiosae meirei) against A's claim on Y for this ¥3 million amount.

- June 29, 1999: This main execution attachment order was served on Y. Upon service, X acquired the right to collect this portion of the debt directly from Y (取立権 - toritateken).

- Y's Payments to A During the "Gap": Crucially, between June 27, 1996, and July 1, 1997, Y had made payments to A (the original debtor) or had otherwise taken steps that fully extinguished A's ¥3 million+ "Honken Saiken" claim against Y. This period was after Y had been served with X's provisional attachment order (May 3, 1997), which should have prevented Y from validly making such payments to A that could prejudice X. However, these payments occurred before Y was served with X's main execution attachment order (June 29, 1999).

- X's Withdrawal of the Provisional Attachment: Sometime after the main execution attachment was in place, X applied to the court to withdraw its initial provisional attachment application and the execution thereof. The stated purpose for this withdrawal was to enable X to obtain a court decision releasing the security (担保 - tanpo) that X had been required to deposit when first obtaining the provisional attachment order (a common requirement under CPRA Article 14 to cover potential damages to the debtor if the provisional attachment proved wrongful).

- X's Collection Lawsuit: X then filed a collection lawsuit (取立訴訟 - toritate soshō) against Y, seeking to recover the over ¥3 million based on the strength of its main execution attachment order. Y defended by asserting that its debt to A (and thus to X as A's attaching creditor) had already been extinguished by the payments it made to A during the 1996-1997 period.

The Lower Courts' Position: Withdrawal Nullifies Prior Prohibition

Both the Sapporo District Court (first instance) and the Sapporo High Court (on appeal) ruled against X and dismissed its collection claim. Their consistent reasoning was:

- The provisional attachment and the subsequent main execution attachment can and do coexist (this is known as the "coexistence theory" or 併存説 - heizonsetsu). The provisional attachment does not simply merge into or disappear upon the commencement of main execution.

- Therefore, a creditor's application to withdraw the provisional attachment, even after main execution has begun, is procedurally valid.

- When a provisional attachment is withdrawn, its legal effects—including the crucial prohibition on the third-party debtor (Y) making payments to the original debtor (A)—are extinguished retroactively. This is based on Article 7 of the CPRA, which applies by analogy Article 262, Paragraph 1 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) concerning the effect of withdrawing a lawsuit (i.e., it is treated as if it had never been filed).

- Consequently, Y's payments to A, although made at a time when the provisional attachment's payment prohibition was technically in effect, became retroactively valid and effective as a discharge of Y's debt to A once X withdrew the provisional attachment.

- Thus, Y could validly raise these payments as a defense against X's collection efforts under the main execution attachment.

X appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: Upholding Coexistence and Retroactive Annulment

The Supreme Court, in its decision of June 7, 2002, dismissed X's appeal, fully endorsing the reasoning of the lower courts.

Core Holding: The Supreme Court affirmed that if a creditor withdraws their provisional attachment, even after having transitioned to main execution against the same claim, the legal effect of that provisional attachment, including the prohibition on the third-party debtor making payments to the original debtor, is extinguished retroactively. As a result, any payments made by the third-party debtor to the original debtor during the period when the provisional attachment was effective but before the main execution attachment was served on the third-party debtor become valid payments. The third-party debtor can then successfully use these payments as a defense against the creditor's subsequent collection action based on the main execution attachment.

Key Elements of the Supreme Court's Reasoning:

- Effect of Provisional Attachment on Third-Party Debtor (CPRA Art. 50(1)): The Court reiterated that when a third-party debtor (like Y) is served with a provisional attachment order concerning a monetary claim they owe to the original debtor (A), they are prohibited from paying that debt to A, at least in a way that would prejudice the attaching creditor (X). If they make such a payment, they cannot typically assert it as a defense against X.

- Duration and Source of the Prohibitive Effect: This prohibitive effect is a direct consequence of the provisional attachment itself. It lasts as long as the provisional attachment remains legally in force and ceases if the provisional attachment is terminated (e.g., by withdrawal, revocation, or fulfillment of its purpose).

- Coexistence of Provisional Attachment and Main Execution: The Supreme Court explicitly stated that this principle "remains unchanged even after main execution has commenced." This is a clear endorsement of the "coexistence theory" (heizonsetsu). The provisional attachment does not automatically cease to exist or merge into the main execution attachment; both can legally exist side-by-side, each with its own procedural basis and effects, although they secure the same underlying substantive claim.

- Retroactive Extinguishment upon Withdrawal (CPRA Art. 7, applying CCP Art. 262(1)): The crux of the decision lies in the effect of withdrawing the provisional attachment. The Court applied the general principle that when a legal proceeding is withdrawn by the applicant, it is treated for most legal purposes as if it had never been initiated. Article 7 of the CPRA states that unless otherwise specified, the provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure apply to provisional remedy proceedings. CCP Article 262, Paragraph 1 stipulates that a lawsuit, once withdrawn, is deemed to have not been pending from the outset. By analogy, the withdrawal of the provisional attachment (both the application for the order and its execution) means that its legal effects, including the payment prohibition imposed on Y, were retroactively nullified.

- Consequence for the Third-Party Debtor's Prior Payments: Therefore, when X withdrew its provisional attachment, the legal barrier that had previously prevented Y's payments to A from being effective against X was removed, and this removal had retroactive effect. Y's payments to A—made during the "gap" when the provisional attachment was in force but before the main execution attachment was served on Y—were thus validated ex post facto as proper discharges of Y's debt to A. Y could therefore successfully assert these now-valid payments as a defense against X's collection lawsuit, even though that lawsuit was based on a main execution attachment.

Theories on the Relationship Between Provisional Attachment and Main Execution

This Supreme Court decision is particularly significant for its clear adoption of the "coexistence theory" (heizonsetsu) concerning the interplay between provisional attachment and main execution. Legal scholarship had previously debated several theories:

- Absolute Extinction Theory (絶対消滅説 - zettai shōmetsu setsu): The oldest view, suggesting that the provisional attachment is entirely extinguished upon the commencement of main execution and does not revive even if the main execution is later withdrawn or cancelled.

- Conditional Extinction/Revival Theory (条件付消滅説・消滅復活説 - jōken-tsuki shōmetsu setsu / shōmetsu fukkatsu setsu): This theory proposed that the provisional attachment is extinguished upon main execution but can revive if the main execution ends for reasons other than full satisfaction of the creditor (e.g., if the creditor withdraws the main execution).

- Latent Continuance Theory (潜在的存続説 - senzai-teki sonzoku setsu): Under this view, the provisional attachment becomes dormant or "latent" within the main execution but retains its potential existence and can re-emerge as an independent measure if the main execution is terminated under certain conditions (excluding situations where the underlying claim itself is found to be non-existent).

- Coexistence Theory (併存説 - heizonsetsu): This theory, which had become the majority scholarly view even before this ruling and was adopted by the lower courts in this case, posits that the provisional attachment continues to exist alongside the main execution, each maintaining its own legal effects and procedural status.

The Supreme Court's 2002 decision provided definitive high-level endorsement for the coexistence theory, although it did not explicitly detail its reasons for choosing this theory over others in this specific judgment. The lower courts, however, had reasoned that this approach allows, for example, third parties who acquire rights in the attached property after the provisional attachment but before the main execution to still pay off the provisional attachment creditor to clear that specific encumbrance, which implies the continued independent existence of the provisional attachment.

The Practical Dilemma for Creditors

The ruling, while providing legal clarity, highlights a practical dilemma for creditors who have obtained a provisional attachment and later proceed to main execution:

- Reclaiming Security Deposits: Creditors are often required to lodge a security deposit with the court when obtaining a provisional attachment (CPRA Art. 14). This security is intended to cover potential damages the debtor might suffer if the provisional attachment later proves to have been unjustified. Once main execution (based on a confirmed right like a final judgment) is underway, the creditor may naturally wish to withdraw the provisional attachment to recover this (often substantial) security deposit, as the main execution itself now provides a more definitive basis for seizure.

- The Risk of Withdrawal: However, as this Supreme Court decision clarifies, withdrawing the provisional attachment to reclaim the security deposit carries the risk of retroactively validating any payments the third-party debtor might have made to the original debtor during the "gap" period (i.e., after service of the provisional attachment but before service of the main execution attachment). This could lead to the creditor being unable to collect the full amount under their main execution attachment if such "gap" payments have depleted the third-party debtor's obligation.

Creditors must therefore carefully weigh the benefit of recovering their security deposit against the risk of potentially legitimizing prior payments made by the third-party debtor.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's June 7, 2002, decision is a landmark for its explicit endorsement of the "coexistence theory" regarding provisional attachments and subsequent main executions, and for its clear articulation of the consequences of withdrawing a provisional attachment in such a scenario. By holding that the withdrawal leads to a retroactive nullification of the provisional attachment's payment prohibition effect, the Court has provided a definitive, albeit potentially challenging for creditors, rule. This judgment underscores the importance for creditors to be acutely aware of the legal effects of their procedural choices, as an action taken to simplify matters or recover security (like withdrawing a provisional attachment) can have unintended and significant consequences on their ability to ultimately recover their debt from a third-party obligor if that obligor made payments during the now-annulled provisional attachment period. The decision emphasizes that even seemingly superseded interim measures can cast a long shadow unless their termination is handled with a full understanding of its retroactive implications.