The Lingering Director: Liability After Resignation but Before Deregistration in Japan – A Supreme Court Perspective

Case: Action for Damages

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of April 16, 1987

Case Number: (O) No. 678 of 1983

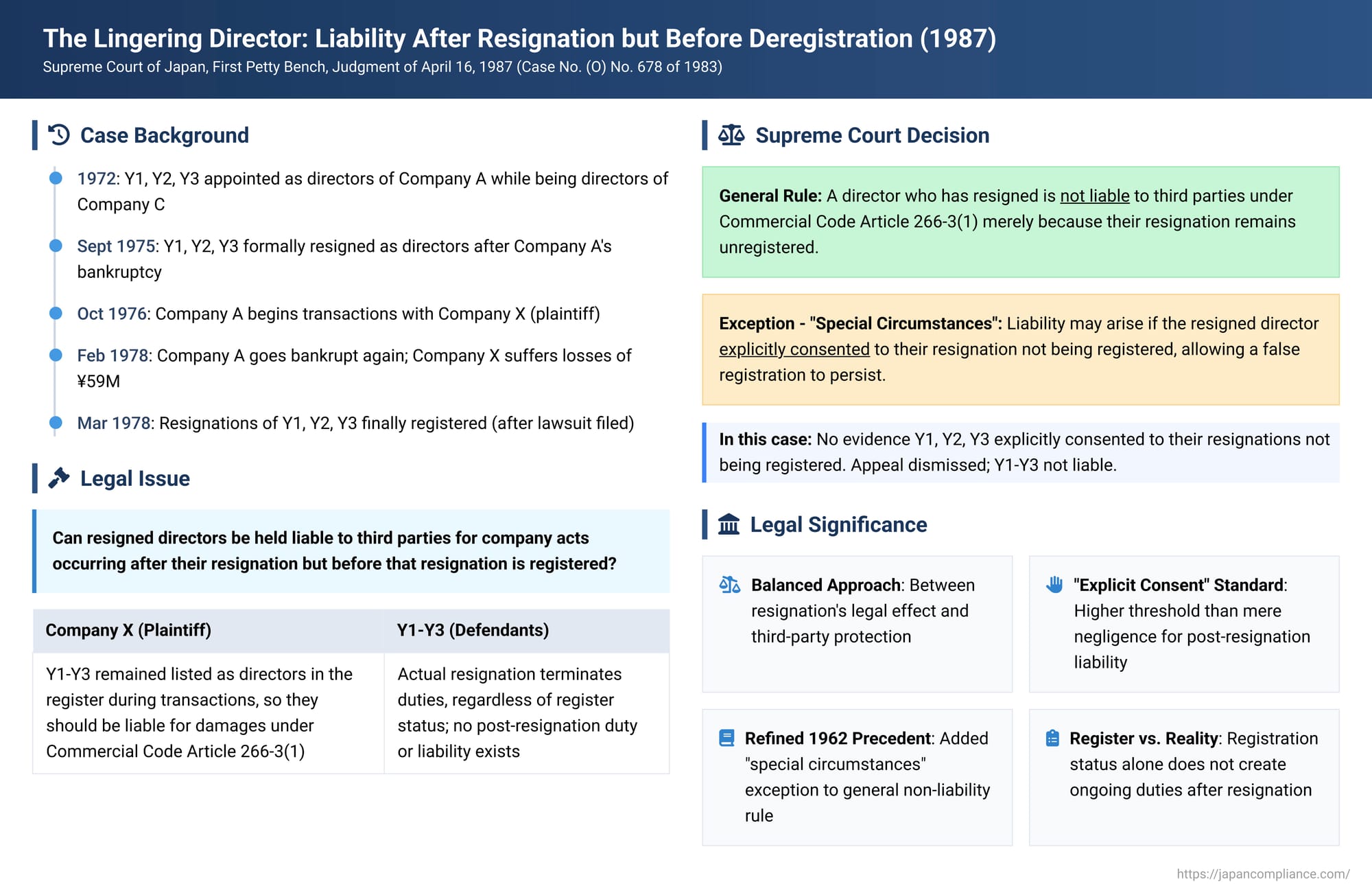

In the world of corporate governance, the accuracy of the commercial register (登記簿 - tōkibo) is paramount for third parties who rely on its information when dealing with companies. But what happens when a director formally resigns, yet the company, for various reasons, fails to update the register to reflect this change? If a third party subsequently suffers losses in transactions with the company, believing the individual is still a director based on the outdated public record, can that resigned director be held personally liable? A key Supreme Court decision on April 16, 1987, addressed this complex issue, delineating a narrow path to post-resignation liability based on "special circumstances," particularly the resigned director's explicit consent to the persistence of the false registration.

A Director on Paper, But Not in Practice: Facts of the Case

The case involved Company A, a metal plating business established in 1967. In 1972, Company A's representative director, B, sought financial assistance from Company C, a separate entity with which Company A had a business relationship. Company C agreed to provide this aid.

As part of the arrangement, ostensibly to allow Company C to monitor Company A's management, three individuals – Y1, Y2, and Y3 (the defendants/appellants) – were appointed as directors of Company A. However, Y1, Y2, and Y3 were also full-time directors at Company C, and their actual involvement in the day-to-day management of Company A was minimal. Their participation was largely limited to attending an annual board meeting of Company A and offering comments on financial documents prepared by RD B.

Company A's financial situation did not improve, and around the end of August 1975, it effectively went bankrupt. At the first creditors' meeting in September 1975, Y1, Y2, and Y3 formally communicated their intention to resign as directors of Company A to RD B. B acknowledged and accepted their resignations. From this point forward, Y1, Y2, and Y3 ceased all activities as directors of Company A. Importantly, their resignations did not cause the number of remaining directors at Company A to fall below any statutory minimum (implying other directors were still in place or could be appointed).

However, RD B, who was preoccupied with attempting to salvage Company A's failing business, neglected to take the necessary legal steps to register the resignations of Y1, Y2, and Y3 in Company A's commercial register. As a result, their names remained listed as current directors. These resignations were only officially registered in March 1978, significantly later and, crucially, after the lawsuit leading to this Supreme Court case had already been initiated.

Following the initial bankruptcy and the resignations of Y1-Y3, RD B decided to try to continue Company A's business. Around October 1976, Company A began direct business dealings with Company X (the plaintiff/respondent). Unfortunately, from around December 1976, Company A started receiving defective goods from Company X, leading to damage claims from Company A's own customers and a severe tightening of its cash flow. Company A then resorted to "dumping" products purchased from Company X at prices below cost simply to generate immediate cash (a practice known as バッタ売り - batta-uri). This unsustainable situation led to Company A's second and final bankruptcy in February 1978.

Company X was left with unrecoverable trade debts from Company A amounting to approximately 59 million yen. Seeking to recoup its losses, Company X filed a lawsuit against Y1, Y2, and Y3. X argued that, because Y1-Y3 were still listed as directors of Company A in the commercial register at the time of X's transactions with A, they should be held liable for X's damages. The claim was primarily based on an analogy to the then-Commercial Code Article 14 (which deals with liability for false entries in the commercial register, now similar to Article 908, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act), seeking to apply this to the provisions for directors' liability to third parties found in Article 266-3, Paragraph 1 of the then-Commercial Code (now Article 429, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act).

The Lower Courts' Conflicting Rulings

The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court) found Y1, Y2, and Y3 liable to Company X. It reasoned that a resigned director could be held responsible if they knew their resignation was not registered and negligently allowed this false registration to persist, or if they were grossly negligent in not knowing that their name remained on the register. The District Court found that Y1-Y3 had been grossly negligent in not confirming that their resignations had been properly registered and thus held them liable, albeit with a finding of significant comparative negligence on the part of Company X (9/10 of the fault attributed to X, and 1/10 to Y1-Y3).

The Tokyo High Court, on appeal, reversed this decision. It held that a director's resignation takes absolute effect internally within the company without needing to await registration. Once resigned, a director has neither the legal power nor the duty to perform directorial functions, such as attending board meetings or supervising other directors. Even if third parties might mistakenly believe them to be directors due to the outdated register, if the events causing damage to the third party (like X's dealings with Company A and A's subsequent failure) occurred after the directors had effectively resigned, those resigned directors could not be said to have caused the damage through bad faith or gross negligence in the performance of any ongoing duties. The High Court thus concluded that Y1, Y2, and Y3 were not liable. Company X appealed this ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Narrow Path to Post-Resignation Liability

The Supreme Court dismissed Company X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that Y1, Y2, and Y3 were not liable under the specific facts of this case. However, in doing so, it articulated an important exception to the general rule of non-liability for resigned directors.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Balancing Resignation's Effect with Third-Party Protection

The Supreme Court's reasoning carefully navigated between the legal effect of a director's resignation and the potential for third-party reliance on public records:

- General Rule – No Liability for Resigned Directors Who Cease to Act: The Court reaffirmed a principle established in one of its earlier precedents (a Third Petty Bench judgment of August 28, 1962): A person who has resigned as a director of a company is generally not liable to a third party under Commercial Code Article 266-3, Paragraph 1 (director's liability to third parties for bad faith or gross negligence in performing duties) merely because their resignation has not yet been registered and the third party, relying on the register, believed them to still be a director when transacting with the company.

This general rule of non-liability applies unless the resigned director, despite having tendered their resignation, actively and intentionally continued to perform acts as if they were still a director, either externally (in dealings with third parties) or internally within the company. - The Exception – Liability Arising from "Special Circumstances," Notably Explicit Consent to False Registration: The Supreme Court then carved out a crucial exception. Liability for a resigned director can arise, even if they no longer actively participate in management, if "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) exist. The primary example of such special circumstances provided by the Court is where the resigned director has explicitly consented to the company's representative (the person responsible for making registration applications, typically the RD) not filing the resignation登記 (registration) and thereby allowing an untrue registration (their name remaining as director) to persist in the commercial register.

- Legal Basis for the Exception – Analogy to Liability for False Registration: The Court grounded this exception in an analogy to Article 14 of the then-Commercial Code (now substantially similar to Article 908, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act). Article 14 stipulates that a person who, either intentionally or negligently, makes an untrue entry in the commercial register, or allows such an untrue entry to remain, cannot assert the untruth of that entry against a third party who relied on it in good faith.

By analogy, if a resigned director explicitly agrees to their name remaining on the register as a director, they are effectively complicit in the persistence of an untrue public record. In such a case, they should not be permitted to later deny their director status when a good-faith third party, relying on that register, seeks to hold them accountable. This inability to deny director status then opens the door to potential liability under Commercial Code Article 266-3, Paragraph 1, as if they were, for legal purposes concerning that third party, still a director. - Application to the Facts – No "Special Circumstances" Proven: In the present case, the Supreme Court found that Company X had not alleged or proven that Y1, Y2, and Y3, at the time of their resignation or subsequently, had given any explicit consent to RD B to refrain from registering their resignations. Nor were any other "special circumstances" tantamount to such consent demonstrated.

- Conclusion on Liability: Therefore, because these "special circumstances" were not established, the general rule of non-liability for resigned directors (who did not continue to act as such) applied. Y1, Y2, and Y3 were not liable to Company X under Article 266-3, Paragraph 1.

Analysis and Implications: The Fine Line of Post-Resignation Responsibility

This 1987 Supreme Court decision is a critical piece of jurisprudence that refines the understanding of a resigned director's potential liability when their departure is not promptly reflected in the public commercial register.

- The Problem of "Directors on the Register":

The commercial register is a cornerstone of corporate transparency and third-party reliance in Japan. However, discrepancies can arise. Liability concerns for individuals listed as directors on the register, but who may not actually (or no longer) hold that position, typically fall into two scenarios:- Never Validly Appointed but Registered (and Consented): A 1972 Supreme Court case dealt with individuals who were never properly appointed as directors but whose names were registered as such with their consent. That court held them liable by analogy to Article 14 (liability for false registration) if they were at fault (intentional or negligent) regarding the false registration. Their consent made them complicit in the false appearance, preventing them from denying their director status against good-faith third parties, which in turn could lead to liability under Article 266-3(1) (now Article 429(1)).

- Validly Appointed, Subsequently Resigned, but Resignation Unregistered: This was the scenario in the 1987 case.

- The Baseline: The 1962 Supreme Court Precedent:

The 1987 Court explicitly referenced its 1962 precedent. That earlier case established that if a director resigns and thereafter does not engage in any further acts as a director, they are generally not liable to third parties under Article 266-3(1) simply because their resignation remains unregistered. The reasoning was that Article 12 of the then-Commercial Code (now similar to Article 908, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act, which states that an unregistered fact cannot be asserted against a good-faith third party) estops the company or the resigned director from asserting the fact of resignation against a good-faith third party. However, Article 12 does not impose an affirmative duty on the resigned individual to act as a director or create liability for inaction after resignation. Since Article 266-3(1) liability is predicated on a director's "bad faith or gross negligence" in performing their duties, a resigned director who has no remaining duties cannot breach them by mere passivity. - The 1987 Refinement: "Special Circumstances" and "Explicit Consent":

The 1987 Supreme Court decision affirmed the general rule from 1962 but critically added the "special circumstances" exception, with "explicit consent to the false registration remaining" as the prime example. This brings the treatment of resigned-but-unregistered directors closer to that of never-appointed-but-registered-with-consent directors, but only under very specific conditions.

The requirement of "explicit consent" is key. The Supreme Court set a higher bar than the first instance court, which had found liability based on the resigned directors' gross negligence in merely not ensuring their resignations were registered. The Supreme Court's standard implies a more active or knowing participation by the resigned director in the decision to allow their name to misleadingly remain on the public record. Mere passive knowledge that the registration hasn't been updated, or even simple negligence in not following up, would likely not suffice under this "explicit consent" standard. - Rationale for the Stricter "Explicit Consent" Standard for Resigned Directors:

Why did the Supreme Court require such a high threshold as "explicit consent" for resigned directors, as opposed to, say, mere negligence in allowing the false registration to persist?- A director who has resigned has formally severed their primary legal relationship with the company.

- Crucially, a resigned director typically has no direct legal power or primary duty to effect the registration of their own resignation; that responsibility lies with the company, usually acting through its representative director.

- Unlike an individual who consents to an initial false registration of their appointment (where they are actively involved in creating the false appearance), a resigned director is in a more passive position regarding the correction of the register.

Thus, to hold them liable requires a stronger indication of their complicity in the continued false public record, such as their explicit agreement that the company should not proceed with the deregistration.

- What if the Resigned Director Continues to Act as a Director?

Both the 1962 and this 1987 Supreme Court judgment indicate that if a person, despite having resigned, "actively and intentionally continued to perform acts as if they were still a director," they could indeed be held liable. This liability might arise either because their conduct estops them from denying their director status vis-à-vis third parties who relied on their actions (under principles related to then-Commercial Code Article 12), or potentially because they might be treated as a "de facto director" (事実上の取締役 - jijitsujō no torishimariyaku). De facto directors – those who act as directors without formal valid appointment but are held out as such – are generally subject to the same duties and liabilities as de jure directors, including liability to third parties.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of April 16, 1987, provides crucial guidance on the delicate issue of a resigned director's liability when their name inaccurately remains on the commercial register. The Court reaffirmed that a director who has genuinely resigned and ceases to act as such is generally shielded from liability to third parties for subsequent corporate actions, even if the company negligently fails to update the public record. However, this shield is not absolute. If it can be proven that "special circumstances" exist, most notably that the resigned director gave explicit consent to the company's representative to allow the false registration (their name remaining as director) to persist, then they may be estopped from denying their director status to good-faith third parties. In such a scenario of complicity, they could face liability as if they were still a director, including potential liability under Article 429, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act for harm caused to third parties due to bad faith or gross negligence in (deemed) directorial duties. This judgment carefully balances the legal effect of a director's resignation with the need to protect third parties who rely on the public commercial register, but only when the resigned director has played a culpable role in the continuation of the misleading public record.