The Limits of Relief: Can a Specific Performance Creditor Directly Claim an Asset After Avoiding a Fraudulent Conveyance?

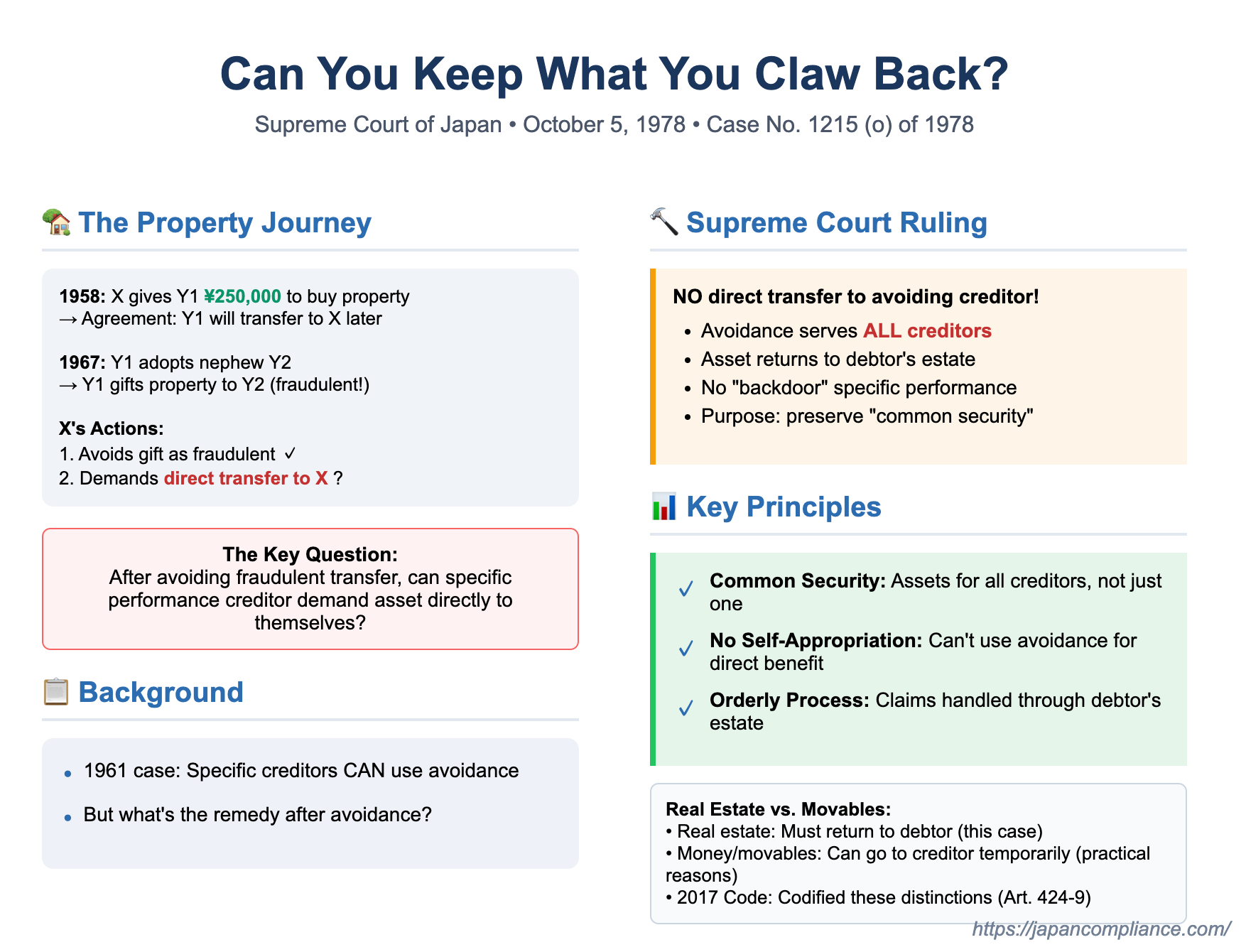

Following up on the landmark 1961 Japanese Supreme Court decision that allowed creditors with claims for specific assets (not just money) to use the fraudulent conveyance avoidance tool (sagai kōi torikeshi), a crucial question remained: what exactly is the remedy for such a creditor? If they successfully avoid a debtor's fraudulent transfer of the specific asset they were entitled to, can they demand that the asset be transferred directly to them?

The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this pivotal issue in its judgment on October 5, 1978 (Showa 53 (O) No. 1215), in a case concerning land ownership. This ruling clarifies the nature and limits of the relief available, reinforcing the fundamental purpose of the fraudulent conveyance system.

A Quick Recap: The 1961 Precedent

Before diving into the 1978 case, it's essential to recall the Supreme Court's Grand Bench decision of July 19, 1961. That judgment overturned prior law by establishing that creditors holding specific performance claims (e.g., a claim for the transfer of a particular piece of real estate) could indeed invoke the creditor's avoidance right. The reasoning was that such claims could ultimately convert into monetary damages claims if performance became impossible. Therefore, like purely monetary claims, they needed the protection of the debtor's general assets, and the avoidance right served to preserve these assets if depleted by fraudulent acts leading to the debtor's insolvency.

Facts of the 1978 Case (X v. Y2 & Y3)

The 1978 case presented a complex factual scenario:

- The Initial Agreement (X and Y1): Around 1958, an individual, Y1, was a tenant in a property owned by A. Faced with a demand from A to either purchase the property (land and building) or pay higher rent, Y1, who was in financial difficulty, entered into an agreement with X. X was seeking a property for a beauty salon.

- On June 21, 1958, X provided Y1 with 250,000 yen to purchase the property from A.

- In return, Y1 agreed to transfer ownership of the property to X at some unspecified future date. The formal registration of this transfer to X was to occur either by mutual agreement or upon Y1's death. Until then, X would lease a portion of the building from Y1. The lower courts later characterized this agreement as a "posthumous gift" (shiin zōyo) from Y1 to X.

- Y1 used X's funds to purchase the property from A, and ownership was registered in Y1's name on June 26, 1958.

- The Subsequent Gift (Y1 to Y2): Years later, Y1, reportedly dissatisfied with X (e.g., over rent increase refusals) and concerned about financial security in old age, decided to adopt her nephew, Y2, and his wife, Y3. In exchange for their care, Y1 intended to gift the property to Y2.

- The adoptions were formally registered on May 31, 1967.

- On November 15, 1967, Y1 gifted the entire property to Y2.

- The ownership transfer from Y1 to Y2 was registered on November 17, 1967. At this point, Y1 apparently had insufficient other assets, making this gift potentially detrimental to X's pre-existing claim.

- X's Lawsuit and the Appeals:

- X sued Y2, seeking the avoidance of the gift from Y1 to Y2 as a fraudulent conveyance. X also demanded the cancellation of Y2's ownership registration (this was X's "Second Claim"; Y1 was involved in a separate "First Claim," details of which are not central here).

- The first instance court ruled in X's favor on this Second Claim, ordering the avoidance of the gift and the cancellation of Y2's registration.

- Y1 and Y2 appealed this decision. (During the appellate proceedings, Y1 passed away, and Y2 and Y3, as her adopted children and likely heirs, succeeded to her position in the lawsuit).

- In the appellate court, X filed a supplementary appeal, adding two crucial claims against Y1 (now her successors, Y2 and Y3):

- Primary Claim: A demand for the direct transfer of the property's ownership registration from Y1's estate to X, based on the original 1958 posthumous gift agreement.

- Alternative Claim: A claim for monetary damages due to Y1's failure to perform the ownership transfer obligation (i.e., impossibility of performance, as the property had been gifted to Y2).

- The appellate court's decision was mixed:

- It upheld the first instance court's decision to avoid the Y1-Y2 gift and cancel Y2's registration (dismissing Y2 and Y3's appeal on this point).

- However, regarding X's supplementary claims:

- It dismissed X's primary claim for direct ownership transfer registration to X.

- It partially granted X's alternative claim for damages, ordering Y2 and Y3 to each pay X 1.48 million yen plus interest.

- X's Appeal to the Supreme Court: X appealed to the Supreme Court, primarily challenging:

- The appellate court's dismissal of X's primary claim for direct ownership transfer registration. X argued this was erroneous.

- The calculation of damages awarded in the alternative claim, alleging errors and inconsistencies.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (October 5, 1978)

The Supreme Court's First Petty Bench delivered a judgment that, while addressing the damages calculation (and remanding that part for reconsideration), provided a definitive answer on the crucial point of direct transfer:

On the Claim for Direct Ownership Transfer to X: The appeal was dismissed.

The Court began by reaffirming its 1961 Grand Bench ruling:

- A creditor with a specific performance claim (like X's claim for the property based on the posthumous gift agreement) can indeed use the fraudulent conveyance avoidance right if the debtor (Y1) disposes of that specific asset and becomes insolvent. This is because such a claim can ultimately transform into a claim for monetary damages and thus, like any monetary claim, deserves to be secured by the debtor's general assets.

However, the Court then drew a critical distinction regarding the purpose and effect of the avoidance:

- Purpose of Avoidance is Common Security: The creditor's avoidance right under Article 424 of the Civil Code is fundamentally aimed at preserving the debtor's general assets as common security for all creditors. The ultimate goal is to enable creditors to receive value-based satisfaction (i.e., typically monetary payment) from these preserved general assets.

- No Self-Appropriation of the Specific Asset: Given this underlying purpose, the Court declared that a creditor holding a specific performance claim cannot appropriate the specific asset itself for the satisfaction of their own claim through the mechanism of fraudulent conveyance avoidance.

- Lower Court Upheld: Therefore, the appellate court's decision that X was "not permissible...to directly demand ownership transfer registration to oneself based on a claim for delivery of a specific thing" was ultimately correct.

In essence, while X could get the fraudulent gift to Y2 nullified (restoring the property, at least notionally, to Y1's estate), X could not use that same avoidance action to have the property registered directly in X's own name.

Delving Deeper: The Rationale and Implications

This 1978 judgment significantly clarifies the operational effect of fraudulent conveyance avoidance for specific performance creditors.

The "Common Security for All Creditors" Principle is Paramount

The Court's reasoning hinges on the core tenet that the avoidance right is not a tool for an individual creditor to achieve preferential satisfaction of their specific claim. Instead, it serves to undo the damage caused by the debtor's fraudulent act to the collective pool of assets available to all of the debtor's creditors. The recovered asset (or its value) is meant to return to the debtor's estate, where it can then be subject to the claims of all creditors according to their legal priorities.

Allowing the avoiding specific performance creditor to directly take the asset for themselves would undermine this principle. It would effectively grant that creditor a super-priority or a direct enforcement mechanism for their specific claim, bypassing the general process of satisfying creditors from the debtor's estate.

No Backdoor Specific Performance

The ruling prevents the specific performance creditor from using the avoidance action as a kind of "backdoor" to achieve the actual performance of their original contract. The 1961 decision allowed them into the "avoidance club" because their claim could become a damages claim. The 1978 decision ensures that once the asset is clawed back, the process of distributing the debtor's assets (or their value) remains orderly and respects the rights of other potential creditors. The specific creditor's claim, especially if the debtor remains insolvent, would typically then be handled as a claim (often for damages, if the specific asset is not available or must be liquidated) against the debtor's now-augmented estate.

Distinguishing Real Estate from Movables/Money

Legal commentary and subsequent statutory developments support a distinction in how recovered assets are handled.

- Movables and Money: For practical reasons, established case law, now codified in the reformed Civil Code (Article 424-9), allows an avoiding creditor to demand direct payment of money or delivery of movables to themselves. This is not for immediate appropriation to their own debt but because the debtor might refuse to accept the recovered assets, frustrating the purpose of the avoidance. The creditor then holds these for the benefit of the common pool of creditors, subject to proper accounting.

- Real Estate: The situation with real estate is different. Ownership registration can be restored to the debtor by a court judgment (e.g., under Article 63 of the Real Property Registration Act). The problem of the debtor refusing to accept the restored title doesn't arise in the same way. Therefore, there is no practical necessity to allow the avoiding creditor to demand direct registration of real estate in their own name for the purpose of preserving common security. The 1978 ruling aligns with this, ensuring the real property returns to the debtor's estate.

What Happens After the Asset is Restored to the Debtor?

This is a complex and much-discussed issue. The 1978 case was somewhat unique in that X's claim for direct transfer from Y1 (her successors) was bundled within the same lawsuit as the avoidance of the Y1-Y2 gift. The Court could thus simultaneously order the cancellation of Y2's registration and reject X's claim for direct transfer.

But what if the avoiding creditor first succeeds in having the title restored to the debtor, and then separately sues the debtor for specific performance of the original contract to transfer the asset? Or what if the debtor, after the asset is restored, attempts to voluntarily transfer it to that specific creditor?

- Legal scholars note that simply explaining the specific creditor's claim as having "transformed into a damages claim" might not fully address these scenarios.

- Before the 2017 Civil Code reforms, one explanation for why the debtor could not then simply transfer the asset to the avoiding specific creditor was the theory of "relative effect" of avoidance – the idea that the avoidance didn't directly affect the debtor's legal position, only that of the beneficiary and subsequent transferees. However, the reformed Civil Code (Article 425) now clarifies that the effect of avoidance also extends to the debtor, making this explanation less viable.

- A more current theoretical approach suggests that property restored to the debtor's estate through a fraudulent conveyance action might be considered a type of "special asset," subject to a purpose restriction – meaning it is earmarked for the satisfaction of the entire body of creditors and cannot be disposed of by the debtor in a way that contravenes this purpose (e.g., by preferentially transferring it to the one creditor who initiated the avoidance).

Consistency with Real Property Registration Rules (Article 177)

Denying direct transfer registration to the avoiding creditor also maintains greater consistency with Article 177 of the Civil Code, which governs the perfection of real property rights through registration. If a specific performance creditor (who might not have initially registered their claim or been in a position to do so against third parties) could obtain direct registration through avoidance, it could create further tensions with the principles of real property registration and third-party rights. The 1978 ruling sidesteps such direct conflict.

Conclusion: Reinforcing the System's Purpose

The Supreme Court's October 5, 1978 judgment is a critical clarification in the law of fraudulent conveyances. It affirms that while creditors with specific performance claims are entitled to use the powerful tool of avoidance to claw back assets their debtor has wrongfully disposed of, the remedy's design is to replenish the debtor's estate for the benefit of all creditors. It is not a mechanism for the avoiding creditor to achieve direct, preferential satisfaction of their specific contractual entitlement to the asset itself. The focus remains steadfastly on the preservation of common security and ensuring a value-based satisfaction for the general body of creditors.