The "LEONARD KAMHOUT" Case: When Withdrawn Consent Derails a Trademark Application in Japan

Judgment Date: June 8, 2004

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 15 (Gyo-Hi) No. 265 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

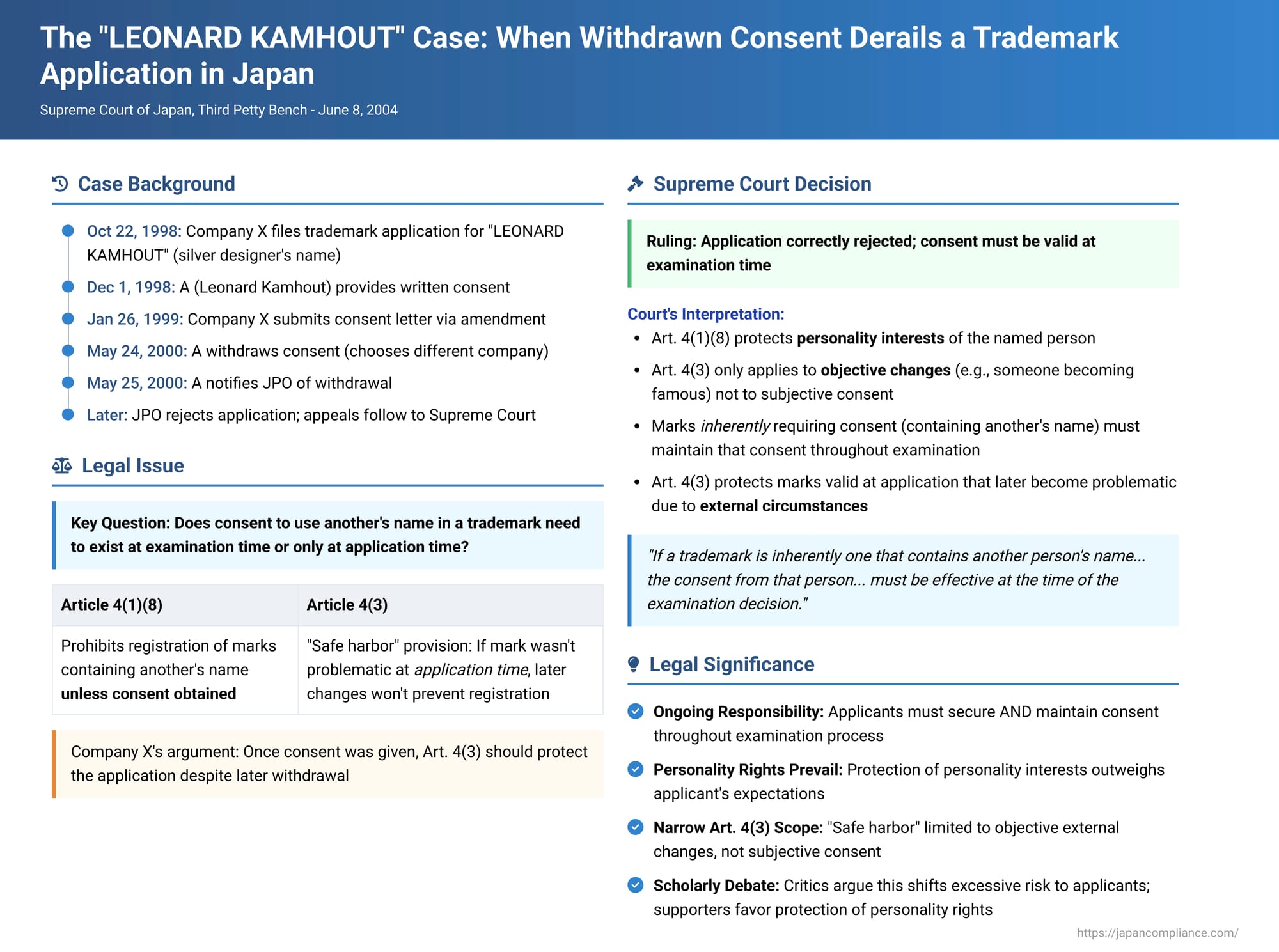

The "LEONARD KAMHOUT" case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court, provides crucial clarification on the registrability of trademarks that include another person's name, particularly when consent for such use is given but later withdrawn before the trademark examination process concludes. The ruling meticulously dissects the interplay between Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 8 (which governs trademarks containing others' names) and Article 4, Paragraph 3 (which provides a limited "safe harbor" for certain changes occurring post-application) of the Japanese Trademark Law. The Court ultimately found that consent must be effective at the time of the examination decision for marks inherently requiring it.

Background of the Dispute: A Designer's Name and Shifting Alliances

The appellant, Company X, filed a trademark application on October 22, 1998, for the mark "LEONARD KAMHOUT" in block Roman letters. The designated goods included precious metals, bags, and apparel. This trademark consisted of the name of A, a well-known American silversmith and designer of silver accessories.

Under Japanese Trademark Law, Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 8 (hereinafter "Item 8") stipulates that a trademark containing "the portrait, personal name, name or famous pseudonym, stage name, or pen name of another person, or a famous abbreviation of any of these" cannot be registered, unless "the consent of the other person concerned has been obtained." Given that the applied-for mark was A's name, A's consent was a prerequisite for its registration.

Company X, which imported and sold silver accessories from international designers, had initially planned to enter into a designer contract with A. Both parties had agreed that Company X would file the trademark application for "LEONARD KAMHOUT".

At the time of the initial trademark application, a formal document showing A's consent was not submitted to the Japan Patent Office (JPO). However, on January 26, 1999, Company X filed an amendment to its application, attaching a consent letter from A, dated December 1, 1998, which explicitly agreed to Company X registering the trademark.

Subsequently, A's business plans changed, and he decided to enter into a designer contract with a different company. Consequently, on May 25, 2000, A submitted a formal notice to the JPO stating that he had withdrawn his previously given consent for Company X's trademark application, attaching a copy of the withdrawal notice sent to Company X dated May 24, 2000.

The JPO ultimately issued a decision rejecting Company X's trademark application. The examiner reasoned that since the consent form was not attached at the very moment of filing, and the later submission via amendment did not have retroactive effect to cure this initial defect, the application failed the requirements of Item 8 from the outset. The JPO thus found it unnecessary to even consider the potential application of Article 4, Paragraph 3 (hereinafter "Paragraph 3"), which provides certain exceptions. Company X appealed this rejection to the JPO's appeal board, but the board upheld the examiner's decision of refusal.

Company X then filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn the JPO's decision. It argued that the JPO's refusal to acknowledge the retroactive effect of the amendment submitting the consent was improper, and that the JPO had misinterpreted both Item 8 and Paragraph 3. The Tokyo High Court dismissed Company X's suit. Company X then successfully petitioned the Supreme Court to hear the case.

The Supreme Court's Dissection of the Law

The Supreme Court dismissed Company X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions but providing a more detailed legal rationale, particularly concerning the interpretation of Item 8 and Paragraph 3.

I. The Purpose of Article 4(1)(viii) (Item 8)

The Supreme Court first reiterated the fundamental purpose of Item 8. This provision, which makes trademarks containing another's portrait, name, famous abbreviation, etc., unregistrable (unless the person's consent is obtained), is primarily aimed at protecting the personality interests (人格的利益 - jinkakuteki rieki) of that other person. From this, the Court deduced that an applicant wishing to register such a trademark bears the responsibility of securing and maintaining the concerned person's consent throughout the process to ensure that these personality interests are not infringed.

II. The Purpose of Article 4(3) (Paragraph 3)

Next, the Court addressed Paragraph 3. This paragraph states that even if a trademark falls under one of the non-registrable categories listed in Article 4, Paragraph 1 (including Item 8) at the time of the examination decision (査定時 - sateiji, which includes the initial examination or the appeal board's decision), the prohibitive provision (like Item 8) will not be applied if the trademark did not fall under that category at the time of the trademark application (出願時 - shutsuganji).

The Court explained that this provision operates on the premise that the primary point for judging whether a trademark is unregistrable is generally the sateiji. Paragraph 3 acts as a specific exception to this general rule. Its purpose is to provide relief in situations where a trademark application was perfectly acceptable under provisions like Item 8 at the shutsuganji, but due to objective changes in circumstances beyond the applicant's control occurring between the application date and the sateiji, the mark then falls foul of Item 8. Examples of such changes could include another person with the same name emerging into public consciousness, or an abbreviation of someone's name becoming famous during that interim period. In such scenarios, the Court reasoned, it would be unfair to deny registration to the applicant. Thus, Paragraph 3 is intended to allow registration in these limited situations where the grounds for refusal arose post-application due to external factors.

III. The Interplay of Item 8 (Consent Proviso) and Paragraph 3

This was the heart of the Court's decision. The Court considered how Paragraph 3 interacts with the consent aspect of Item 8:

- The phrase in Paragraph 3, "a trademark... which did not fall under ... Item 8... at the time of application," should be interpreted as referring to a trademark that did not fall under the main body (本文 - honbun) of Item 8 at the shutsuganji. The "main body" of Item 8 is the part that describes the prohibited content (e.g., containing another's name).

- Crucially, if a trademark did fall under the main body of Item 8 at the time of application (i.e., it inherently contained another person's name) but was only rendered acceptable by virtue of the consent proviso (括弧書 - kakko gaki) of Item 8, then Paragraph 3 does not apply to such a situation.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded, if a trademark inherently contains another person's name (thus engaging the main body of Item 8), the applicant must ensure that the consent from that person, as required by the proviso in Item 8, is effective at the time of the examination decision (sateiji).

- Even if such consent was present at the time of application (or validly submitted thereafter via amendment), if this consent is subsequently withdrawn and is lacking at the sateiji, the trademark cannot be registered.

IV. Application to the "LEONARD KAMHOUT" Case Facts

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found:

- The applied-for trademark "LEONARD KAMHOUT" clearly fell under the main body of Item 8 at the time of application because it consisted of A's name.

- It was undisputed that at the time of the sateiji (the JPO's decision-making point), A's consent for Company X to register the trademark was no longer in effect due to the withdrawal.

- Therefore, the application for "LEONARD KAMHOUT" was correctly rejected because the trademark fell under Item 8 due to the lack of effective consent at the decisive moment.

Broader Implications and Analysis

The Supreme Court's decision in the LEONARD KAMHOUT case carries significant implications:

- Retroactive Effect of Amendments: While the JPO had initially argued that the late submission of the consent letter was not retroactive, the Supreme Court's judgment appears to have implicitly accepted the retroactive validity of the amendment that introduced the consent. The Court proceeded with its analysis on the premise that consent had been established post-filing, focusing instead on the effect of its subsequent withdrawal. This suggests that procedural amendments to submit initially missing consent are generally considered to have retroactive effect, making the JPO's initial reasoning on this specific point questionable.

- Timing of Judgment for Non-Registrability: The case reinforces the general principle that the assessment of whether a trademark meets registration requirements is made at the sateiji. Paragraph 3 provides a very specific carve-out for issues that arise post-application due to objective, uncontrollable changes, not for issues like withdrawn consent which relates to the applicant's ongoing responsibility.

- The Crucial Distinction for Paragraph 3 Application: The Court drew a critical line: Paragraph 3 is designed to protect applicants from unforeseen external events that make a previously compliant mark non-compliant. It is not designed to protect an applicant when a mark always required consent (because it inherently included another's name) and that consent is later lost. The responsibility to maintain such consent lies with the applicant.

- Legislative Intent of Paragraph 3: The commentary on the case notes that Paragraph 3 was introduced into the Trademark Law to address concerns that applicants whose filings were initially valid could be unfairly rejected due to lengthy examination delays during which circumstances might change. The Supreme Court, however, interpreted this intent narrowly, limiting its application to changes in the objective applicability of the main body of Item 8, not to the subjective element of consent.

- Scholarly Debate: The Supreme Court's decision spurred considerable academic discussion:

- Supporters of the Court's View (Negative View on Applying Paragraph 3 to Consent): This perspective emphasizes that the applicant bears the ongoing responsibility to secure and maintain the consent. The primary goal is to protect the personality interests of the person whose name is used. If consent is withdrawn, the applicant's recourse should be through general civil law remedies (e.g., breach of contract or tort against the person withdrawing consent), not through a forced trademark registration against that person's will.

- Critics of the Court's View (Positive View on Applying Paragraph 3 to Consent): This view questions the basis for placing the entire burden of maintaining consent on the applicant, especially if withdrawal is arbitrary. They argue that civil remedies may be insufficient and that the applicant has a reasonable expectation of registration once consent is given, which Paragraph 3 should protect, especially from delays in the examination process.

- Eclectic/Intermediate View: This approach generally sides with the Court but suggests an exception where the withdrawal of consent is an abuse of rights by the consenting party and the applicant is entirely blameless. In such specific cases, the withdrawal might be deemed ineffective. However, this view faces criticism regarding the practical difficulty for the JPO to assess the "reasonableness" of consent withdrawal during the trademark examination process.

- Critique of the Supreme Court's Prioritization: The author of the provided commentary leans towards the "Positive View," suggesting that the legislative history of Paragraph 3, focused on protecting applicants from adverse effects of examination delays, might warrant its application even in cases of withdrawn consent. The commentary argues that personality rights, while important, are not so absolutely protected under trademark law post-registration (e.g., Item 8 non-compliance arising after registration due to consent withdrawal is not an explicit ground for invalidation under Article 46(1)(vi) if consent was valid at registration) as to always outweigh the applicant's reasonable expectations.

Conclusion

The LEONARD KAMHOUT Supreme Court decision provides a definitive statement on a critical aspect of Japanese trademark law: for trademarks that inherently involve another person's name and thus require their consent under Article 4(1)(viii), that consent must be valid and effective at the time of the JPO's examination decision (or subsequent appeal board decision). The "safe harbor" provision of Article 4(3), designed to protect applicants from certain intervening external changes, does not extend to situations where consent, once given, is later withdrawn. This ruling underscores the applicant's responsibility to manage their relationship with the consenting party and ensure that such consent remains robust throughout the registration process if their mark is to proceed. It highlights the primacy of protecting personality interests when consent is at issue, even if it leads to outcomes that may seem harsh to applicants who once held that consent.