The Kozosushi Saga: When Fame and Market Reality Reshape Trademark Battles in Japan

Judgment Date: March 11, 1997

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 6 (O) No. 1102 (Trademark Infringement Injunction, etc. Claim)

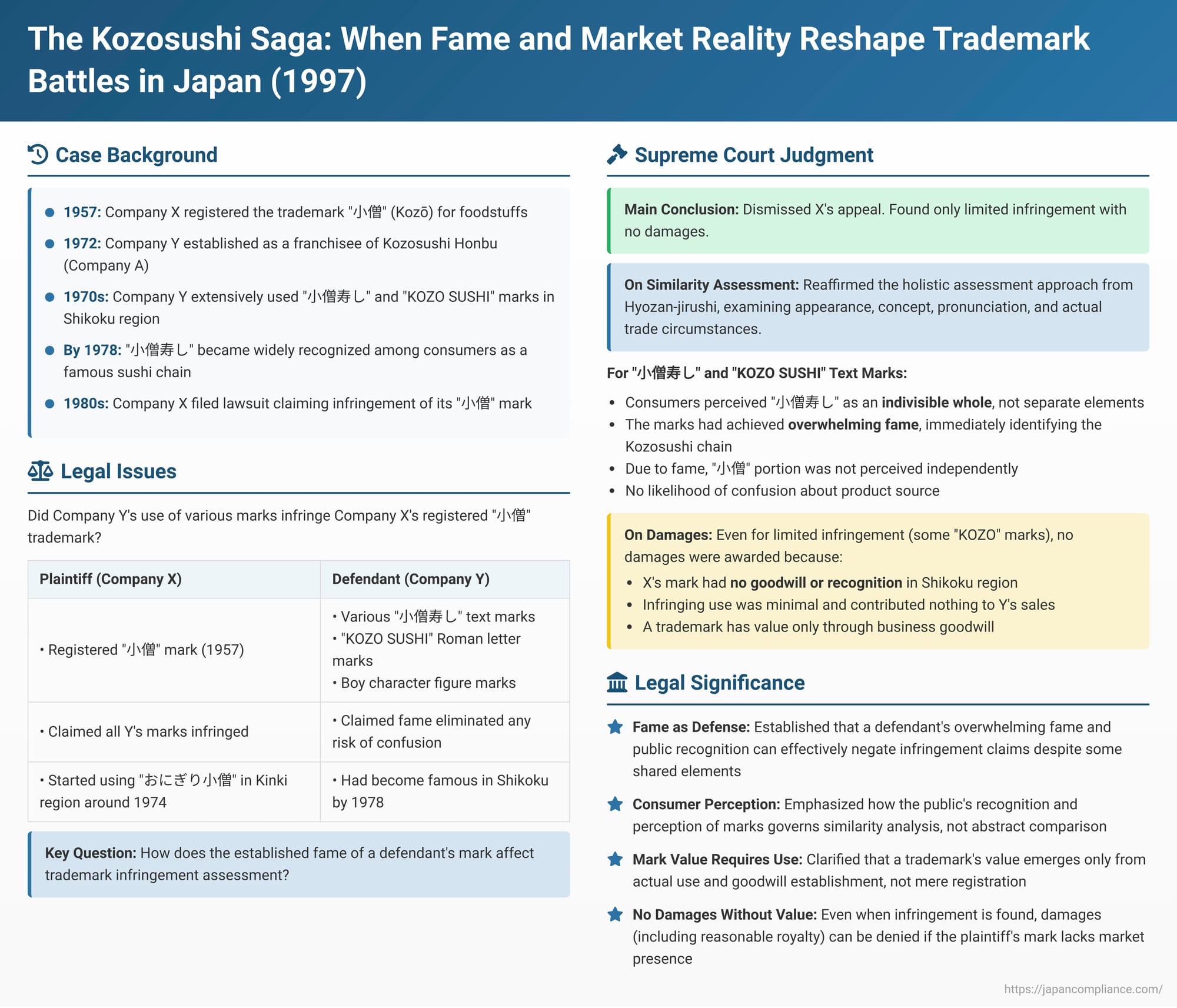

The "Kozosushi" (小僧寿し - Little Monk Sushi) case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1997, is a highly influential judgment in trademark infringement litigation. It profoundly illustrates how the established fame and market perception of a defendant's brand can significantly impact the assessment of trademark similarity and the likelihood of consumer confusion. Furthermore, the case provides critical insights into the calculation, or rather the denial, of damages when the plaintiff's registered trademark possesses little to no independent goodwill or customer appeal in the relevant market.

The Players and Their Marks: A Tale of Sushi Franchises

The appellant, Company X, was the owner of a registered trademark consisting of the kanji characters "小僧" (Kozō), written vertically. This mark, translating to "little monk" or "young apprentice/shop-boy," was registered way back in 1957 for a broad category of "foodstuffs and seasonings not belonging to other classes."

The appellee, Company Y, was a corporation established in 1972 with the business of manufacturing and selling take-out sushi. Company Y operated under a franchise agreement with a separate entity, Company A (the franchisor, widely known as Kozosushi Honbu). Company Y was a significant franchisee and also acted as a sub-franchisor for other加盟店 (member stores/franchisees) in the Shikoku region of Japan.

Company Y and its network of franchisees extensively used a variety of marks (the "Y Marks") on their store signboards, packaging, and advertising materials in the Shikoku region. These Y Marks included:

- Y Mark Group 1: Text marks featuring "小僧寿し" (Kozosushi), presented in various layouts (e.g., "小僧寿し," "し寿僧小" - a stylized vertical arrangement).

- Y Mark Group 2: Text marks using Roman letters, such as "KOZO," "KOZO SUSHI," "KOZOSUSI," and "KOZO ZUSHI."

- Y Mark Group 3: Figure marks depicting a characteristic cartoon image of a young boy (presumably the "little monk").

Company X initiated a trademark infringement lawsuit against Company Y, claiming that the use of these Y Marks infringed its registered "小僧" trademark. Company X sought an injunction to stop the use of the Y Marks and also claimed monetary damages.

The lower courts (Kochi District Court and Takamatsu High Court) found only limited infringement. Specifically, they held that only some of Y's Roman letter marks – Y Mark Group 2(1) ("KOZO") and 2(3) (a different style of "KOZO") – infringed Company X's trademark. For the more prominent "小僧寿し" text marks and the figure marks, the courts either found no similarity or ruled that Company Y's use was permissible under specific defenses (such as Article 26, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Trademark Law, which allows the use of one's own name or its famous abbreviation in a normal manner, finding "小僧寿し" to be a famous abbreviation of the Kozosushi chain). Dissatisfied with this limited finding of infringement, Company X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Approach to Trademark Similarity in a Real-World Context

The Supreme Court dismissed Company X's appeal, upholding the lower courts' finding of limited infringement and denial of damages where infringement was found. The Court's reasoning provides a masterclass in applying trademark similarity principles to complex market realities where one party (the defendant) possesses overwhelming brand recognition.

I. General Principles of Trademark Similarity (Reaffirming Hyozan-jirushi)

The Court began by reiterating the established general principles for assessing trademark similarity, referencing its landmark decision in the Hyozan-jirushi (Iceberg Mark) case:

- The similarity of trademarks should be determined based on whether their use on identical or similar goods is likely to cause misidentification or confusion as to the source of those goods.

- This determination requires a holistic assessment of the overall impression, memory, and associations that the trademarks convey to traders and consumers, derived from their appearance (外観 - gaikan), concept or idea (観念 - kannen), and pronunciation (称呼 - shōko).

- This analysis must also be grounded in the specific "actual circumstances of trade" (取引の実情 - torihiki no jitsujō) for the relevant goods, insofar as these circumstances can be clarified.

- Importantly, similarity in one or more of these three aspects (appearance, concept, pronunciation) is merely a prima facie indicator of potential confusion. If other aspects are markedly different, or if the actual circumstances of trade negate any likelihood of confusion, the marks should not be considered similar.

II. Application to Y's Text Marks (e.g., "小僧寿し," "KOZO SUSHI")

The Supreme Court then applied these principles to Company Y's various text-based marks, focusing heavily on the impact of the Kozosushi chain's fame:

- Overwhelming Fame of the "小僧寿し" (Kozosushi) Franchise: The Court acknowledged the lower court's finding that, by 1978 at the latest (well within the period relevant to the infringement claim), the name "小僧寿し" had become widely recognized among general consumers as an abbreviation for Company A (the Kozosushi Honbu or headquarters) or, more broadly, the entire Kozosushi franchise chain. When consumers encountered the characters "小僧寿し" or heard the pronunciations "Kozōzushi" or "Kozōsushi," they would immediately associate these with the Kozosushi Honbu or the Kozosushi chain as the source of the take-out sushi.

- Holistic Perception and Indivisibility of Y's Marks: The Court reasoned that consumers typically pronounce "小僧寿し" as a single, integrated unit. Therefore, marks like "小僧寿し," "KOZO SUSHI," "KOZOSUSI," and "KOZO ZUSHI" were perceived by the public as indivisible wholes. These complete marks generated the pronunciation "Kozōzushi" or "Kozōsushi" and signified either the corporate group of the Kozosushi chain or the take-out sushi products manufactured and sold by that chain.

- No Separate Consumer Perception of "小僧" (Kozō) or "KOZO" within Y's Marks: Given this strong, unified perception of Y's marks, the Supreme Court concluded that it was not possible to say that only the "小僧" or "KOZO" part of these marks would give rise to a separate, distinct pronunciation "Kozō" (like X's mark) in the minds of consumers. Similarly, these isolated parts ("小僧" or "KOZO") within Y's marks would not independently evoke the generic meaning of "a young male shop assistant" (one of the dictionary meanings of "小僧"). The dominant association was with the entire, famous "Kozosushi" entity.

- Conclusion on Y's Text Marks: Although Company X's trademark "小僧" and Company Y's various text marks (like "小僧寿し") shared some visual commonality (the "小僧" characters) and a partial phonetic element ("Kozō"), the "小僧" or "KOZO" segments within Y's highly famous composite marks did not function as independent source identifiers. The concept strongly evoked by Y's marks was that of the renowned Kozosushi chain itself or its specific products. In essence, these Y Marks possessed a high degree of distinctiveness in their own right, clearly identifying the Kozosushi chain as the source. Consequently, the Supreme Court found that there was no likelihood of consumers being confused about the source of the goods. These Y text marks were therefore deemed not similar to Company X's "小僧" trademark.

III. Application to Y's Figure Marks (the Boy Character)

The Court applied a similar logic to Company Y's figure marks (the cartoon boy character):

- Inherent Characteristics of the Figure Mark: Visually, the boy character mark was not similar to Company X's text-only "小僧" trademark. While the figure itself might convey a general concept of "a person working at a merchant's house," it did not inherently or directly evoke the more specific concept of "a young male shop assistant" (the primary meaning of "小僧"). Furthermore, the figure mark, in isolation, did not inherently generate the pronunciation "Kozō."

- Acquired Pronunciation and Concept Through Use: The Court acknowledged that even a non-verbal figure mark can acquire specific conceptual associations and even phonetic links through extensive and continuous use, especially when used alongside a well-known name. In this case, Company Y's figure marks had been consistently used together with the "小僧寿しチェーン" (Kozosushi Chain) or "小僧寿し" names at numerous franchisee stores. As a result, by around 1977, consumers seeing the figure mark alone would likely associate it with the famous Kozosushi chain, and it was plausible that the figure mark itself might have come to evoke the pronunciation "Kozōzushi" or "Kozōsushi" in their minds.

- No Likelihood of Confusion Despite Acquired Association: However, even if the figure mark acquired this association with the "Kozosushi" name and pronunciation, this did not mean it had acquired the specific concept of "a young male shop assistant" or the distinct pronunciation "Kozō" (which characterized Company X's mark). Instead, the concept and pronunciation evoked by the figure mark through its widespread use were those of the famous Kozosushi chain itself – the actual and well-recognized source of the products.

- Conclusion on Y's Figure Marks: Therefore, even if one could argue for a partial phonetic overlap (the "Kozō" sound within the acquired "Kozōzushi" pronunciation), given that the figure mark very clearly and distinctively identified the well-known Kozosushi chain as the source, there was no likelihood of consumer confusion with Company X's "小僧" trademark. These Y figure marks were also deemed not similar to Company X's mark.

IV. The Issue of Damages Under Article 38(2) (Reasonable Royalty)

A particularly noteworthy aspect of the Kozosushi judgment is its handling of the damages claim. The High Court had, in fact, found infringement for two of Y's less-used "KOZO" Roman letter marks but had nevertheless denied Company X any monetary damages. The Supreme Court upheld this denial of damages.

- The Nature of Trademark Value: The Court emphasized that, unlike patents or utility models where the invention or device itself possesses inherent economic value, a trademark's value is not intrinsic to the word or symbol itself. Rather, a trademark acquires economic value only when business goodwill (業務上の信用 - gyōmujō no shin'yō) becomes attached to it through use and public recognition.

- Factual Findings Regarding Company X's "小僧" Mark:

- Company X had started selling take-out rice balls and sushi under the name "おにぎり小僧" (Onigiri Kozō – Rice Ball Boy) around 1974, primarily in the Kinki region (around Osaka). However, it had never used its registered "小僧" trademark for selling sushi or any other products in the Shikoku region, which was Company Y's area of operation.

- In stark contrast, by 1978, the name "小僧寿し" had become famous not only as an abbreviation for the Kozosushi Honbu or chain but also as an identifier of the take-out sushi products sold by that chain. Company Y's figure marks had also achieved similar fame and possessed significant goodwill and customer appeal (顧客吸引力 - kokyaku kyūinryoku).

- Company X's "小僧" trademark, having never been used in the Shikoku region, had no public recognition or goodwill there; it possessed virtually no customer appeal or economic value in that specific market.

- Factual Findings Regarding Company Y's Infringing Use of "KOZO": For the limited period where infringement was found by the lower courts (1980-1982), Company Y's use of the specific infringing "KOZO" marks was extremely minimal (e.g., displayed on a window at one store and on a wall at another, among 21 stores in just one prefecture). Company Y overwhelmingly used its main "小僧寿し" text marks and its popular figure marks.

- Conclusion on Damages: The Supreme Court concluded that Company Y's sales were almost exclusively driven by the established fame of the Kozosushi chain, its extensive advertising, the quality of its products, and the powerful customer appeal of its primary "小僧寿し" text and figure marks. The very limited and secondary use of the infringing "KOZO" marks had not contributed in any meaningful way to these sales. Therefore, Company X had not suffered any lost sales. More importantly, the Court held that Company X had also not suffered any loss in the form of a reasonable royalty because its "小僧" trademark had no existing economic value or customer appeal in the Shikoku market that Company Y could have benefited from by using the simple "KOZO" mark.

- Interpretation of Trademark Law Article 38(2): This article allows a trademark owner to claim, as damages, an amount equivalent to what they would normally be entitled to receive for the use of their registered trademark (i.e., a reasonable royalty). While the trademark owner does not need to prove the occurrence of actual damage, the infringer can raise a defense by proving that no damage could possibly have occurred. The Supreme Court reasoned that if a registered trademark has absolutely no customer appeal in the relevant market, and if the infringing use of a similar mark has clearly not contributed at all to the infringer's sales, then it can be said that no damage, even in the form of a lost potential royalty, has actually occurred. To award damages in such a situation where no economic harm is evident would, in the Court's view, go beyond the fundamental framework of tort law.

Broader Implications of the Kozosushi Ruling

The Kozosushi Supreme Court decision has had a lasting impact on trademark law and practice in Japan:

- The Dynamic Nature of Trademark Rights in Infringement Actions: The case starkly demonstrates that the assessment of trademark similarity and the likelihood of confusion in infringement litigation is not a static, abstract exercise. Post-registration market realities, particularly the fame, recognition, and distinctiveness acquired by the defendant's marks and associated business, can profoundly influence the outcome. A defendant's strong, well-established brand identity can effectively "absorb" or redefine elements that might, in a different context, be considered confusingly similar to a plaintiff's less-known mark.

- Importance of Active Use and Goodwill Cultivation: The judgment implicitly underscores the necessity for trademark owners to actively use their marks in commerce and diligently cultivate goodwill and consumer recognition. A registered trademark that languishes unused in a particular market may offer very limited practical protection against later users who independently build up significant brand identity, even if there are some shared elements. The "static" right granted by registration is interpreted dynamically in light of real-world brand perceptions.

- Shift Towards a More Competition-Focused Perspective: The Kozosushi decision is seen by some commentators as reflecting an evolution in Japanese trademark law, moving from a purely property-rights-centric view towards a perspective that gives greater weight to actual competitive conditions and consumer perceptions in the marketplace.

- Strict View on Damages When Plaintiff's Mark Lacks Market Presence: The denial of even a reasonable royalty when the plaintiff's trademark has no established economic value or customer appeal in the specific market where the infringement occurred is a critical takeaway. It highlights that trademark damages are intended to compensate for actual or realistically potential economic harm derived from the value of the mark, not merely to punish the act of using a similar sign.

Conclusion

The Kozosushi Supreme Court case is a multifaceted judgment that provides profound insights into the complexities of trademark infringement analysis in Japan. It powerfully illustrates how the overwhelming fame and distinctiveness of a defendant's brand identity, built through extensive use and marketing, can effectively neutralize potential confusion with a plaintiff's less-known registered trademark, even when there are some overlapping components. The Court's emphasis on the holistic perception of marks within their actual trade context, and its stringent approach to awarding damages where the plaintiff's mark lacks tangible market value, underscores a pragmatic and market-reality-focused approach to trademark disputes. This decision serves as a crucial reference for businesses regarding the importance of not only securing trademark registration but also actively building and maintaining brand strength and consumer recognition.