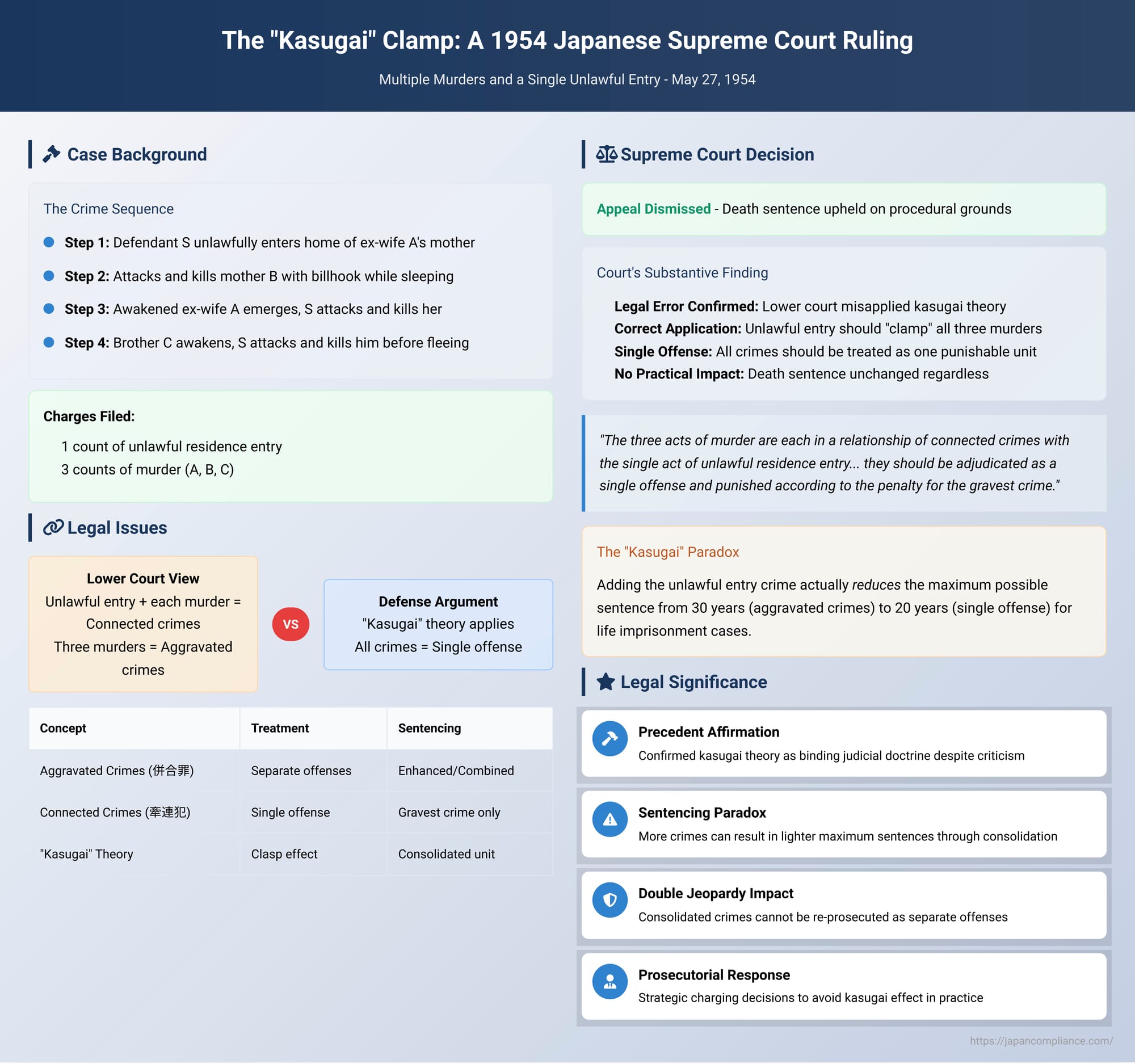

The "Kasugai" Clamp: A 1954 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Multiple Murders and a Single Unlawful Entry

On May 27, 1954, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a decision that, despite its seemingly straightforward outcome, affirmed one of the most intellectually challenging and controversial doctrines in Japanese criminal law: the "kasugai" or "clasp" theory. The case involved a defendant who, after a single act of unlawful entry, committed three separate murders. The Court was asked to decide how these crimes should be grouped for sentencing. While upholding the defendant's death sentence on procedural grounds, the Court's substantive analysis confirmed that a single, lesser crime can act as a "clasp," binding multiple, more severe crimes together into a single punishable offense, paradoxically precluding the application of harsher sentencing rules. This 1954 decision remains a cornerstone for understanding the complex Japanese law of plurality of crimes.

Facts of the Case

The case centered on the brutal actions of the defendant, S. With the intent to murder his ex-wife, A, S armed himself with a billhook (a type of heavy knife) and unlawfully entered the home of A's mother, B. Inside the residence, he first encountered the sleeping figure of B and attacked her with the weapon. The commotion woke A, who was in a separate room. S proceeded to attack and kill her. Subsequently, A's younger brother, C, who had been sleeping beside B, also awoke, whereupon S attacked and killed him as well before fleeing the scene. S was later apprehended and charged with one count of unlawful residence entry and three counts of murder for the deaths of A, B, and C.

Procedural History and the Legal Error

The first instance court, the Akita District Court, found S guilty of all charges. In its application of the law, the court determined that the unlawful entry was a means to the end of committing the murders, establishing a relationship of "connected crimes" (kenrenhan) between the entry and each individual murder. However, it then treated the three murder convictions as separate offenses subject to the rules for aggravated crimes (heigo-zai), which allow for enhanced sentencing. The court ultimately sentenced S to death, selecting this penalty for the murder of C and, in accordance with Article 46 of the Penal Code, did not impose additional sentences for the other crimes.

After the High Court dismissed his appeal, S's defense counsel appealed to the Supreme Court. The core of the appeal was the argument that the lower courts had committed a grave error in applying the law. The defense contended that by treating the three murders as aggravated crimes, the courts had ignored a long-standing judicial precedent, the "kasugai" theory, which dictated that the three murders should have been consolidated into a single punishable offense.

The Core Doctrine: Explaining the "Kasugai" (Clasp) Theory

To understand the Supreme Court's decision, one must first grasp the "kasugai" theory, a unique feature of Japanese criminal jurisprudence. The term "kasugai" refers to a metal staple or clamp used in traditional Japanese carpentry to hold two pieces of wood together. In law, it functions as a metaphor for how crimes can be linked.

The theory operates in a specific context involving two key concepts:

- Aggravated Crimes (Heigo-zai): As governed by Article 45 of the Penal Code, this applies when an individual commits two or more distinct crimes that have not yet been finalized by a court judgment. The sentences for these crimes are typically combined or increased up to a statutory maximum, resulting in a harsher overall punishment. The three murders, viewed in isolation, would naturally be treated as aggravated crimes.

- Connected Crimes (Kenrenhan): This is a form of "constructive consolidation of crimes," where multiple crimes are treated as a single punishable offense. Under Article 54 of the Penal Code, this relationship exists when one crime is the necessary means to commit another, or when one crime is the result of another. A classic example is unlawfully entering a house (the means) to commit theft (the end). These are punished as a single offense, with the sentence determined by the gravest of the crimes involved.

The "kasugai" theory comes into play at the intersection of these two concepts. It posits that if multiple crimes that would normally be treated as aggravated crimes (e.g., Murder X and Murder Y) are each independently "connected" to a common third crime (e.g., Unlawful Entry Z), then crime Z acts as a "kasugai" or "clasp". This clasp binds X and Y together through their shared connection to Z, forcing the entire bundle of crimes (X, Y, and Z) to be treated as a single punishable offense under the rules for connected crimes.

In this case:

- Murder of B (Crime X) was connected to the Unlawful Entry (Crime Z).

- Murder of A (Crime Y) was connected to the Unlawful Entry (Crime Z).

- Murder of C (Crime Y') was connected to the Unlawful Entry (Crime Z).

According to the "kasugai" theory, the single act of unlawful entry should have clamped all three murders together, forming one consolidated, punishable offense. The lower court's failure to do this was the error alleged by the defense.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: An Error Without Injustice

The Supreme Court technically dismissed the appeal on procedural grounds, stating the defense's arguments were not properly raised or ruled upon in the high court. However, exercising its authority to review the case on its own motion, the Court directly addressed the substance of the claim.

The Court explicitly agreed with the defense's legal reasoning. It stated:

"According to the facts established by the court of second instance, the three acts of murder are each in a relationship of connected crimes (kenrenhan) with the single act of unlawful residence entry, and pursuant to Article 54, Paragraph 1, second sentence, and Article 10 of the Penal Code, they should be adjudicated as a single offense and punished according to the penalty for the gravest crime. Therefore, the first instance judgment contains an error in the application of the law on this point, as argued in the appeal."

Despite finding a clear legal error, the Supreme Court refused to overturn the lower court's decision. It reasoned that the error did not result in a "gross injustice" that would necessitate reversal. Since the lower court had already sentenced S to death for one of the murders, and the death penalty is the maximum possible sentence, applying the "kasugai" theory correctly would not have changed the ultimate outcome. The sentence would still have been death. Because the defendant suffered no practical disadvantage from the error, the judgment was allowed to stand.

The significance of the decision lies not in its outcome, but in its explicit affirmation of the "kasugai" theory as binding judicial precedent.

The Contentious Legacy: Criticisms of the "Kasugai" Theory

While the Supreme Court upheld the theory, it has been the subject of intense criticism from legal scholars for decades due to the paradoxical and potentially unjust results it can produce.

- The Sentencing Paradox: The most significant criticism is that the theory creates a situation where committing more crime can lead to a lighter sentencing range. For example, had the court in this case considered a sentence of life imprisonment, the outcome would have been starkly different. For three separate murders treated as aggravated crimes, the maximum term of imprisonment could be extended up to 30 years. However, under the "kasugai" theory, the three murders are consolidated into a single offense, and the maximum term of imprisonment would be capped at 20 years (the maximum for a single count of murder at the time). This creates the absurd result that by adding the crime of unlawful entry, the defendant becomes eligible for a lesser maximum sentence.

- The Double Jeopardy Problem: The theory has profound implications for the principle of ichiji-fusai-ri-kō (the Japanese equivalent of double jeopardy). If a bundle of crimes (X, Y, and Z) is treated as a single offense, a final judgment on any part of that bundle extends legal finality over the entire set. This means if a prosecutor were to discover and prosecute only the unlawful entry (Z) and one murder (X), and a conviction became final, the subsequent discovery of the second murder (Y) would not permit a new prosecution, as it would be considered part of the same offense already adjudicated.

- The Co-conspirator Paradox: The theory can also create imbalances in cases involving multiple offenders. A co-conspirator who participated in all three crimes (the two murders and the clasping offense) could, under the "kasugai" theory, face a lighter sentencing range than a co-conspirator who only participated in the two murders (which would be treated as aggravated crimes).

Responses and Practical Solutions

In response to these issues, academics have proposed various "kasugai-hazushi" (clasp removal) theories to avoid these paradoxes, such as treating only one murder and the entry as a consolidated unit and the other murders as aggravated crimes in relation to that unit.

In practice, a more pragmatic solution has emerged: prosecutorial discretion. To circumvent the "kasugai" effect, a prosecutor can strategically choose to not indict the defendant on the "clasping" crime (in this case, the unlawful entry). By only charging the three murders, they can be treated as aggravated crimes, ensuring the possibility of an enhanced sentence. This procedural workaround, which uses prosecutorial charging decisions to solve a substantive law problem, has been met with both support and criticism but was deemed permissible in a 2005 Tokyo High Court decision.

Conclusion

The 1954 Supreme Court decision in the case of S is a foundational text in Japanese criminal law. It solidified the "kasugai" theory, demonstrating the judiciary's commitment to a formal, logical application of the Penal Code's text, which does not explicitly forbid such a "clasping" effect. However, the decision simultaneously cast a long shadow, highlighting the deep tension between legal formalism and substantive justice. The theory's paradoxical consequences—particularly the potential for lighter sentences for more extensive criminal conduct—have ensured that the "kasugai" clamp remains one of the most debated and fascinating phenomena in Japanese jurisprudence, a point where abstract legal logic collides with the practical realities of punishment and justice.