The Iressa Tragedies: Japan's Supreme Court on Pharmaceutical Product Liability and Warning Adequacy

Date of Judgment: April 12, 2013 (Heisei 25)

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, 2012 (Ju) No. 293

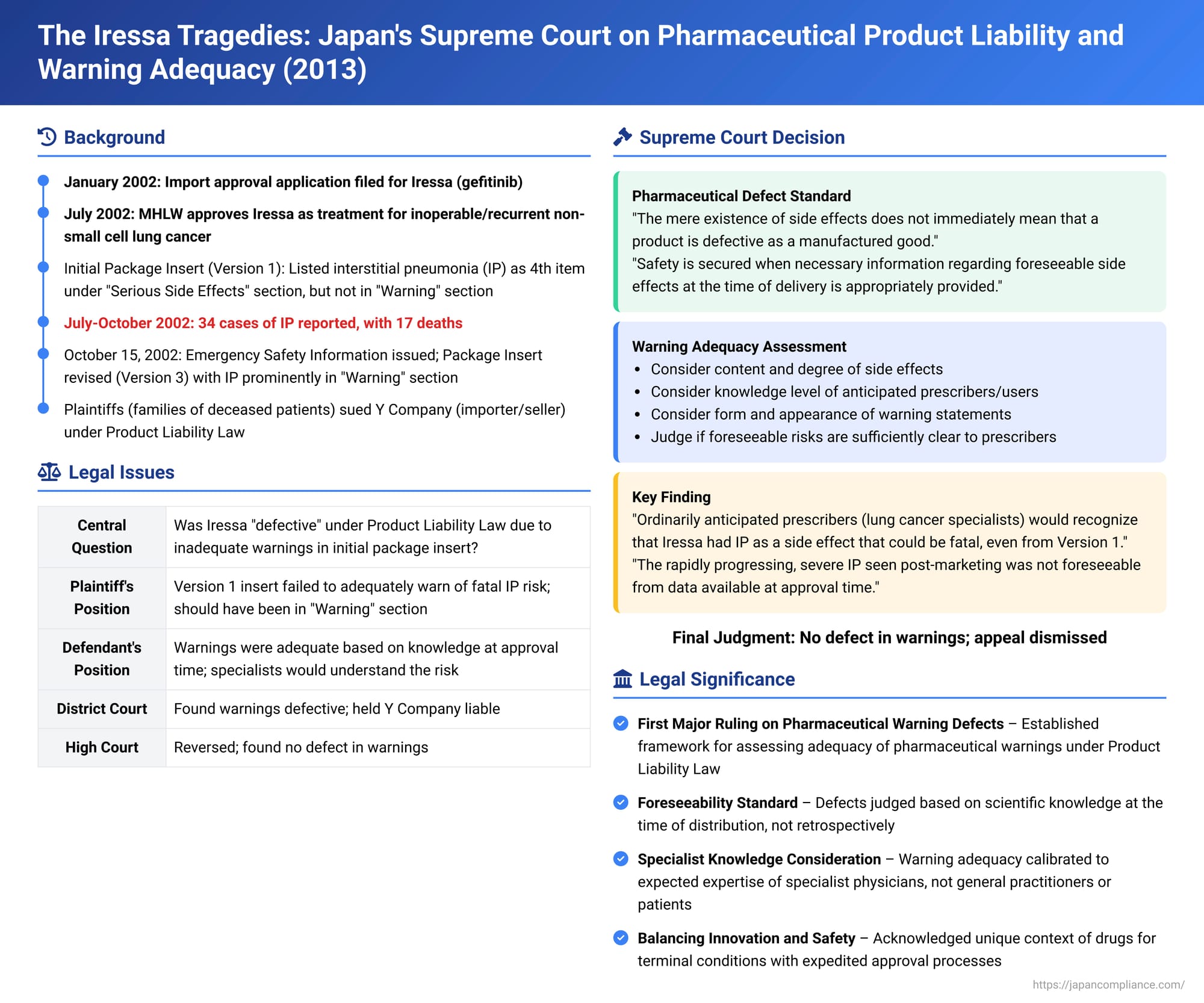

In a landmark decision with profound implications for pharmaceutical product liability in Japan, the Supreme Court on April 12, 2013, ruled on the case of Iressa (gefitinib), a molecular targeted cancer drug. The case centered on whether the drug's importer and seller could be held liable under the Product Liability Law for deaths caused by a severe side effect, interstitial pneumonia (IP), based on alleged defects in the warnings provided in the initial package insert. The Court ultimately found no defect, in a judgment that carefully balanced the inherent risks of potent medicines, the foreseeability of side effects at the time of launch, and the expected knowledge of specialist prescribing physicians.

Factual Background: Iressa – A New Hope with Devastating Side Effects

The Drug and its Approval:

Iressa (generic name: gefitinib) is a molecular targeted therapy developed for the treatment of inoperable or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer, a particularly aggressive and difficult-to-treat form of cancer with a very poor prognosis. Defendant Y, a pharmaceutical import and sales company, applied for import approval of Iressa in Japan in January 2002, submitting data up to Phase II clinical trials. In July 2002, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) granted import approval for Iressa, subject to certain conditions, including the conduct of post-marketing surveillance studies. Iressa was designated as a potent drug and a prescription-only medicine.

The Initial Package Insert (Version 1):

The package insert (添付文書 - tenpu bunsho) accompanying Iressa at its launch (Version 1) listed interstitial pneumonia (IP) as a potential side effect. It was included in the "Serious Side Effects" section, as the fourth item listed, following severe diarrhea, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and liver dysfunction. However, IP was not featured in the prominent "Warning" section at the top of the insert, nor did the entry for IP explicitly state that the condition could be fatal.

The Post-Marketing Crisis:

Soon after Iressa became available in Japan (sales began July 16, 2002), a concerning number of reports emerged of patients developing severe, rapidly progressing IP, many of which resulted in death. By October 11, 2002 (within about three months of launch), 34 cases of IP had been reported to Y Company or the MHLW, with 17 of these resulting in death (some initial reports were later reclassified).

In response to this crisis, on October 15, 2002, Y Company, acting under the guidance of the MHLW, issued an "Emergency Safety Information" bulletin to healthcare professionals. Simultaneously, the package insert for Iressa was urgently revised (Version 3). This revision included the creation of a "Warning" section at the beginning of the insert, which now prominently featured warnings about acute lung disorder and IP. The "Serious Side Effects" section was also updated to list IP first and include stronger cautionary language. Subsequent revisions, such as Version 4 in December 2002 following a MHLW safety review meeting, further strengthened these warnings, advising, for instance, that patients be hospitalized or under equivalent close observation for at least the first four weeks of treatment to monitor for IP. Following these enhanced warnings and information dissemination, the number of reported IP-related deaths associated with Iressa decreased.

The Plaintiffs' Lawsuit:

The plaintiffs (X et al.) were the surviving family members of several patients with terminal non-small cell lung cancer who had been prescribed Iressa and subsequently died from interstitial pneumonia. They filed lawsuits against Y Company (the importer/seller) and the State.

Against Y Company, the plaintiffs alleged that Iressa was defective under Japan's Product Liability Law due to:

- A "design defect" (inherent flaw in the drug's properties).

- A "defect in instructions or warnings" (指示・警告上の欠陥 - shiji・keikoku-jō no kekkan), specifically that the warnings in the initial package insert (Version 1) were inadequate regarding the risk and severity of IP.

Against the State, they alleged a failure to properly exercise its regulatory authority concerning Iressa's approval and oversight. The total damages sought were approximately 77 million yen.

Lower Court Proceedings: A Divergence on Warning Adequacy

- First Instance Court: The trial court denied the existence of a design defect in Iressa. However, it found that the initial package insert (Version 1) did suffer from a defect in its instructions and warnings regarding the risk of IP. Consequently, it held Y Company liable for damages. The court also found the State liable under the State Compensation Law for deficiencies in its regulatory actions.

- High Court: On appeal, the High Court overturned the first instance judgment. It concluded that the warnings in Iressa's initial package insert were not defective. As a result, it dismissed the plaintiffs' claims against Y Company. The claims against the State, which were largely premised on Y Company's liability, were also dismissed without a detailed examination of the regulatory negligence arguments.

The plaintiffs then appealed to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court accepted the appeal for review, but limited its scope to the issue of whether the statements in the Version 1 package insert constituted a "defect" under Article 2, Paragraph 2 of the Product Liability Law.

The Supreme Court's Decision (April 12, 2013)

The Supreme Court, by a unanimous decision of the Third Petty Bench, dismissed the plaintiffs' appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's ruling that Iressa's initial package insert was not defective. The Court's judgment provided its first detailed interpretation of "defect" under the Product Liability Law in the context of pharmaceuticals and warning adequacy.

1. General Principles of Product Defect for Pharmaceuticals:

The Court laid out several key principles:

- (Point ①) Inherent Nature of Pharmaceutical Side Effects: "Pharmaceuticals... are acknowledged to have an inherent characteristic whereby the occurrence of some harmful side effects is unavoidable. The mere existence of side effects does not immediately mean that a product is defective as a manufactured good."

- Achieving Safety Through Information: "Rather, considering their ordinarily anticipated mode of use, the safety that such a product should ordinarily possess is secured when necessary information for the product's use regarding side effects that are foreseeable at the time of delivery is appropriately provided."

- (Point ②) Defect Arising from Inadequate Information: "A situation where the said pharmaceutical is deemed defective may arise with the lack of appropriate provision of such information pertaining to side effects as one element."

2. Adequacy of Package Inserts for Prescription Pharmaceuticals:

- (Point ③) Package Insert as the Proper Channel: "For prescription pharmaceuticals... information regarding the aforementioned side effects should be appropriately stated in the package insert."

- (Point ④) Criteria for Assessing Adequacy: "Whether the statements in the said package insert are appropriate should be judged from the perspective of whether the foreseeable risks of side effects are sufficiently made clear to the said prescribers or users. This judgment should be made by comprehensively considering various circumstances, such as: the content and degree of the side effects (including their frequency of occurrence), the knowledge and capability of the ordinarily anticipated prescribers or users based on the drug's efficacy or effects, and the form and appearance of the side effect statements in the said package insert."

3. Application to Iressa's Initial Package Insert (Version 1):

The Court then applied these principles to the specific facts surrounding Iressa:

- (Point ⑤) The Target Prescribers/Users – Specialist Physicians: "Iressa, at the time of its import approval... was designated, among other things, as a prescription-only medicine with the indication for 'inoperable or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer.' Therefore, its ordinarily anticipated prescribers or users were physicians engaged in the treatment of such lung cancer. According to the established facts, such physicians generally recognized that anticancer drugs have interstitial pneumonia as a side effect, and that if this side effect develops, it can be fatal."

- (Point ⑥) Physician's Interpretation of Version 1 Information: The Court reasoned that when these specialist lung cancer physicians read the statements about IP in the "Serious Side Effects" section of the Version 1 package insert, "it is clear that they would have had no difficulty recognizing that Iressa had a side effect of interstitial pneumonia comparable in nature to that of other anticancer drugs, and that if a patient for whom Iressa was indicated developed interstitial pneumonia due to Iressa administration, it could be fatal." The Court further stated that this understanding "is not affected by the order of listing in the 'Serious Side Effects' section, the content of other listed side effects, or descriptions in medical journals published at the time of this import approval." In essence, the Court believed that the existing general knowledge of oncologists about IP as a potentially fatal side effect of chemotherapy would lead them to understand the risks associated with Iressa, even if Version 1 did not explicitly use the word "fatal" for IP or place it in the main "Warning" box.

- (Point ⑦) Unforeseeability of Rapidly Progressing, Severe Interstitial Pneumonia: Crucially, the Court distinguished between general IP and the specific type of IP that caused many of the Iressa-related deaths. "On the other hand... the symptoms of rapidly progressing, severe interstitial pneumonia cannot be said to be of the same degree as interstitial pneumonia as a side effect of other anticancer drugs, nor can it be said that this [specific aggressive form] could have been foreseen from clinical trials and other information available up to the time of this import approval." The pre-approval clinical trial data for Iressa showed a few cases of IP, but these were generally manageable or their link to Iressa was not definitive, and they did not suggest an unusually high rate or the rapid, severe progression seen post-marketing.

- (Point ⑧) Context of Iressa's Nature and Approval: The Court also considered the specific context of Iressa: "Iressa is indicated for 'inoperable or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer,' which is an intractable cancer with an extremely poor prognosis. At the time, obtaining approval from the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare based on results up to Phase II trials was permitted [for such drugs]. This nature of Iressa as an anticancer drug, including the circumstances of its approval, would also be easily understood by physicians treating such lung cancer." Taking these factors into account, "the absence of a statement [in Version 1] premised on the existence of rapidly progressing, severe interstitial pneumonia as a side effect does not render the statements in the Version 1 package insert... inappropriate."

Conclusion on Defect:

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that the statements in Iressa's Version 1 package insert, when judged against the side effects foreseeable at the time of import approval, could not be deemed inappropriate. Therefore, Iressa was not defective due to inadequate warnings at the time it was placed on the market for the deceased patients in this case. The appeal was dismissed. (The judgment included four supplementary opinions from the justices, further elaborating on aspects like the timing of defect assessment and the nature of foreseeability for side effects).

Analysis and Implications: Balancing Innovation, Risk, and Information

The Supreme Court's Iressa decision is a landmark in Japanese product liability law concerning pharmaceuticals. It provides critical, albeit controversial, guidance on several fronts:

- Defining "Defect" for Pharmaceuticals: This was the Supreme Court's first major pronouncement on what constitutes a "defect" under the Product Liability Law for a pharmaceutical product, focusing specifically on "warning defects." The Court established that the mere existence of side effects does not make a drug defective; rather, defectiveness in the context of warnings hinges on whether information about foreseeable side effects was adequately communicated.

- The "Ordinarily Expected Safety" Standard: For drugs, this safety standard is achieved not by eliminating all risks (which is often impossible), but by providing appropriate information that allows risks to be managed. The adequacy of this information is judged relative to the intended professional user.

- Foreseeability at the Time of Delivery as a Crucial Element: The judgment strongly emphasizes that the adequacy of warnings must be assessed based on the medical and scientific knowledge regarding side effects that was foreseeable at the time the drug was introduced to the market. The particularly aggressive and rapidly fatal nature of some Iressa-induced IP cases was deemed unforeseeable at the time of Iressa's approval based on Phase II data. This aligns with principles similar to the "development risk defense" (though not explicitly invoked as such by the main opinion), where a manufacturer may not be liable for harms caused by dangers that were scientifically unknowable at the time of distribution.

- The Role of the Specialist Prescriber's Knowledge: A key and debated aspect of the ruling is the significant weight given to the expected knowledge and understanding of the specialist physicians prescribing the drug. The Court assumed that oncologists treating advanced lung cancer would inherently understand that IP associated with any anticancer agent could be fatal, even if the Iressa package insert didn't spell this out in the most prominent way initially. This suggests that for highly specialized medications used by experts, the standard for warnings can be calibrated to that expert audience.

- Context of "Last Chance" Drugs and Expedited Approval: The Court acknowledged the specific circumstances surrounding Iressa: it was a novel drug offering hope for patients with an extremely poor prognosis, for whom other treatments had failed. Such drugs often undergo expedited approval processes (like approval based on Phase II trial data for severe, unmet medical needs) to reach patients faster. This context appears to have influenced the Court's assessment of what constituted an "appropriate" warning at the time of launch. The balance between rapid access to potentially life-extending drugs and ensuring full knowledge of all potential risks is a complex one.

- Debate and Criticism: The Iressa decision was, and remains, highly controversial in Japan. Given the large number of deaths and severe illnesses linked to the drug before warnings were strengthened, many patient advocates and legal scholars felt that the ruling set too high a threshold for finding a "warning defect." Critics argued that the Court may have placed undue reliance on the presumed knowledge of specialist physicians and perhaps underestimated the severity and unique nature of Iressa-induced IP that might have been discernible even from early data, or that a more precautionary approach to warnings was warranted. The fact that warnings were drastically strengthened shortly after launch, leading to a decrease in fatalities, was seen by some as evidence that the initial warnings were indeed insufficient.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2013 Iressa judgment is a pivotal decision in Japanese pharmaceutical product liability law. It meticulously outlines a framework for assessing "warning defects" in package inserts, emphasizing the foreseeability of risks at the time of marketing and the expected knowledge level of specialist prescribers. While providing legal clarity on these complex issues, the ruling also sparked considerable debate about the balance between promoting pharmaceutical innovation, managing the inherent risks of potent medications, and ensuring that patients and doctors receive timely and fully adequate information to make informed treatment decisions, especially when dealing with "last-chance" therapies for life-threatening diseases. The case underscores the ongoing challenges in aligning legal standards for product liability with the rapidly evolving landscape of medical science and patient expectations.