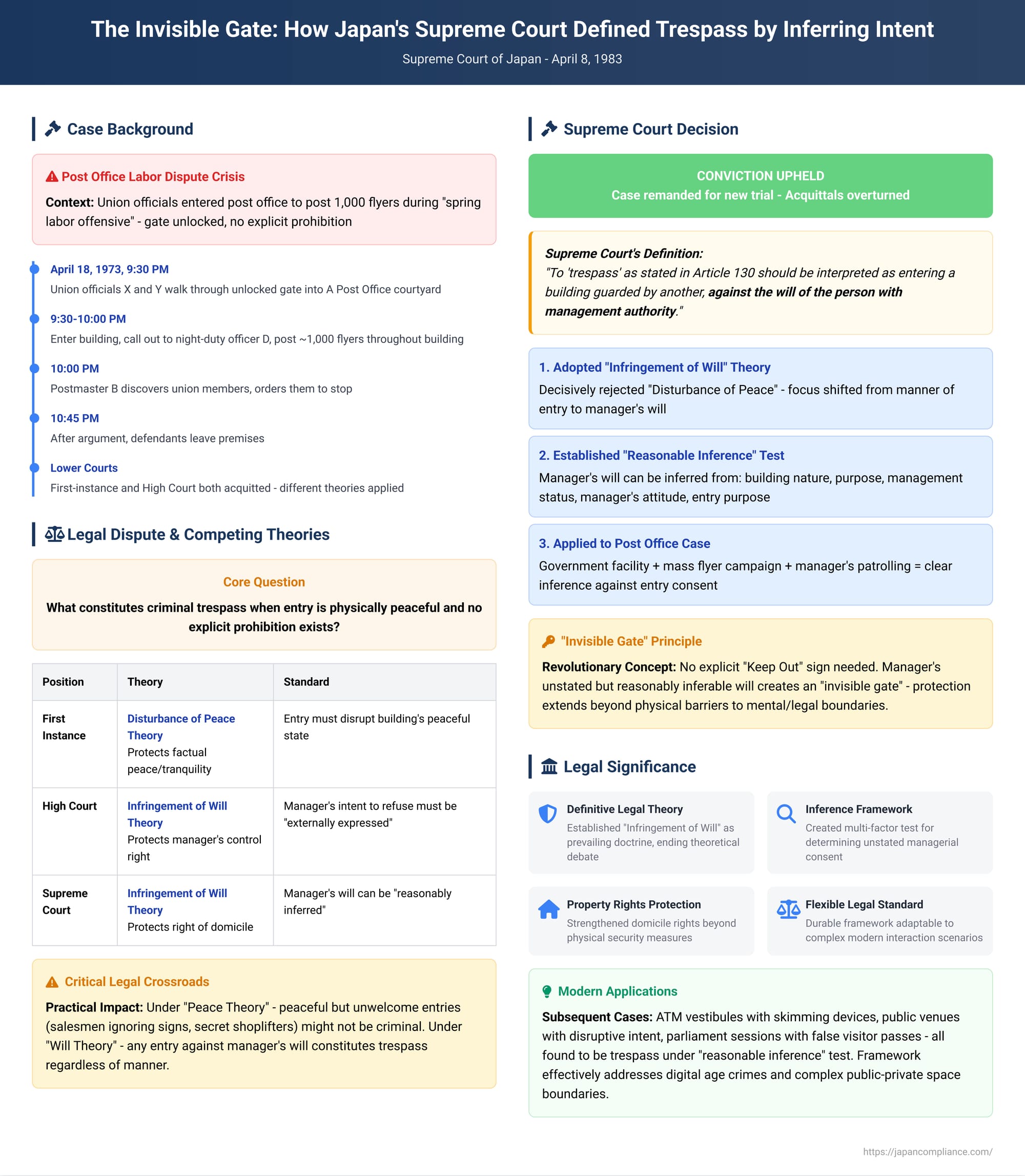

The Invisible Gate: How Japan's Supreme Court Defined Trespass by Inferring Intent

What constitutes a criminal trespass? The answer might seem simple: entering a property after climbing a fence or breaking a lock. But what if the gate is unlocked, the door is open, and no "Keep Out" sign is in sight? Can entering a building under such circumstances still be a crime? On April 8, 1983, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision that addressed this very question, fundamentally shaping the modern understanding of trespass by focusing not on the physical nature of the entry, but on the unstated will of the property's manager.

The case, which arose from a labor dispute at a local post office, forced the court to choose between two competing legal theories: Is trespass a crime against the "peace and tranquility" of a place, or is it a crime against the manager's right to decide who can and cannot enter? The Court's ultimate choice in favor of the latter, and its establishment of a test for "reasonably inferring" a manager's will, remains a cornerstone of Japanese criminal law today.

The Facts: A Union Action at a Post Office

The defendants in the case, X and Y, were employees of the postal service and also officials in their labor union. As part of a nationwide "spring labor offensive" (shuntō), a common tactic in Japanese labor relations, they planned to post a large number of union flyers inside the A Post Office.

The manager of the A Post Office, a man named B, had the legal authority to control the premises. Aware of the union's plans, he intended to prevent the flyer posting. On the night of the incident, he and his deputy, C, were patrolling the building's exterior. However, a complicating factor was that the vast majority of the employees at the A Post Office were union members. Consequently, Postmaster B had not given any specific instructions to the night-duty officer, D, to deny entry to fellow union members or to stop them from posting flyers.

On the evening of April 18, 1973, at around 9:30 PM, defendants X and Y, along with several other union members, proceeded with their plan. They walked through an unlocked gate into the post office courtyard. Upon entering the main building, they called out to the night-duty officer D, "Hey, we're here," and walked inside with their shoes on. Over the next half hour, they affixed approximately 1,000 flyers to windows and other surfaces throughout the building.

Around 10:00 PM, Postmaster B discovered the union members inside. He immediately ordered them to stop, and after an argument, the defendants and their colleagues left the premises at approximately 10:45 PM.

X and Y were subsequently charged with criminal trespass of a building. The lower courts, however, acquitted them. The first-instance court ruled that the defendants' entry did not disturb the "peace" of the building and was therefore not a criminal trespass. The High Court, on appeal, also acquitted them, reasoning that because the postmaster's intent to refuse entry had not been clearly expressed externally, a core element of the crime was missing. The prosecutor then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Crossroads: Two Competing Theories of Trespass

The conflicting lower court rulings reflected a deep and long-standing theoretical divide in Japanese criminal law over the essential nature of trespass. The core question is: what legal interest (hogo hōeki) does the law of trespass protect? Two main theories provide different answers.

- The "Disturbance of Peace" Theory (Heion Shingai Setsu): This theory posits that the law protects the factual state of peace and tranquility within a residence or building. Under this view, an entry only becomes a criminal trespass if it is carried out in a manner that disturbs this peace. This would include entries that endanger life, body, or property. A quiet, non-disruptive entry, even if unwelcome, might not meet the criminal standard. The first-instance court's acquittal of X and Y was based on this theory; their entry was physically peaceful and did not disrupt the post office's after-hours operations.

- The "Infringement of Will" Theory (Ishi Shingai Setsu): This theory argues that the law protects the right of the resident or manager to control their own space—a concept known as the "right of domicile" (jūkyo-ken). According to this view, the crime of trespass is fundamentally about violating the manager's will. Any entry against the manager's will constitutes a trespass, regardless of how peacefully or discreetly it is performed. The manner of entry is less important than the fact that it is unauthorized.

The practical difference is most stark in cases of peaceful but unwanted entry. Under the "Disturbance of Peace" theory, a salesman who ignores a "No Salesmen" sign or a person who enters a department store with the secret intent to shoplift would likely not be guilty of trespass, as their physical entry is outwardly normal and peaceful. The "Infringement of Will" theory, if applied strictly, would likely find both to be acts of trespass because the entry is contrary to the will of the manager.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court rejected the reasoning of the lower courts, overturned the acquittals, and remanded the case for a new trial. In doing so, it decisively adopted the "Infringement of Will" theory as the definitive interpretation of trespass under Japanese law.

The Court articulated a clear definition:

"To 'trespass' as stated in the first part of Article 130 of the Penal Code should be interpreted as entering a building, etc., guarded by another, against the will of the person with management authority."

This declaration shifted the focus of the crime entirely from the manner of the entry to the will of the manager.

The "Reasonable Inference" Test: Reading the Manager's Mind

The most significant contribution of the ruling was its guidance for situations where the manager's will is not explicitly stated. The High Court had acquitted the defendants because the manager's refusal was not "externally expressed". The Supreme Court declared this was the wrong standard. An explicit, proactive refusal is not required.

Instead, the Court established that a manager's will can be reasonably inferred from the totality of the circumstances. Trespass is established if, based on a holistic assessment, it can be "reasonably determined that the person with management authority did not consent to the entry as it actually occurred". The Court provided a non-exhaustive list of factors to consider in this assessment:

- The nature of the building

- Its purpose of use

- Its management status and conditions

- The attitude of the person with management authority

- The purpose of the entry

Applying this new test to the facts, the Supreme Court found it was obvious that the entry was against the postmaster's will. The building was a government facility subject to management regulations. The defendants' purpose was to conduct a mass flyer-posting campaign, an act the postmaster clearly did not permit and which violated internal rules. The postmaster's own actions, patrolling the grounds to prevent this very activity, demonstrated his attitude. Based on these factors, the Court found it was reasonable to conclude the entry was against his will, and that the defendants were aware of this. The fact that the night-duty officer did not stop them was deemed irrelevant, as he had not been granted the authority to permit such an entry.

Legacy and Lingering Debates

The 1983 decision has had a lasting impact, solidifying the "Infringement of Will" theory as the prevailing doctrine in Japanese case law and legal scholarship. Its "reasonable inference" test has been applied in numerous subsequent cases, often broadening the scope of trespass. For instance, courts have found criminal trespass in cases such as:

- Entering a bank ATM vestibule with the hidden purpose of installing a card-skimming device.

- Entering a public venue for a national ceremony with the intent to disrupt it.

- Entering a session of parliament using a visitor's pass obtained with false information.

In all these cases, the physical entry was into a publicly accessible space, but the illicit purpose of the entry placed it outside the scope of the manager's implied consent.

The ruling, however, does not end the debate. Scholars continue to discuss the outer limits of the theory. For publicly accessible places like department stores or hotels, the law recognizes a form of "blanket" or "implied" consent for the general public. The challenge lies in determining the scope of that consent. An entry for the purpose of shopping is clearly within the scope; an entry for the purpose of shoplifting is just as clearly outside of it. The 1983 decision provides the framework—inferring the manager's will from all circumstances—to make these nuanced distinctions.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1983 judgment in the post office trespass case fundamentally clarified that the essence of this crime in Japan is not the disruption of peace, but the violation of a person's right to control their own domain. It established that this right is protected even by an "invisible gate"—the manager's unstated but reasonably inferable will. By providing a multi-factor test to determine that will, the Court created a durable and flexible legal standard that respects property rights while accounting for the complex realities of human interaction in both public and private spaces.