The Imposter's Exam: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on What Makes an Answer Sheet a Legal 'Document'

The high-stakes world of university entrance examinations is a cornerstone of Japan's social and educational structure. The integrity of these exams is paramount. But what happens when that integrity is compromised by an organized "imposter exam-taker" (kaedama juken) scheme? And what is the precise crime being committed? Is an exam answer sheet—a collection of a student's knowledge, thoughts, and guesses—a legally protected "document" in the same way as a contract or a deed? Can forging an answer sheet by having someone else take the test be prosecuted as the serious crime of document forgery?

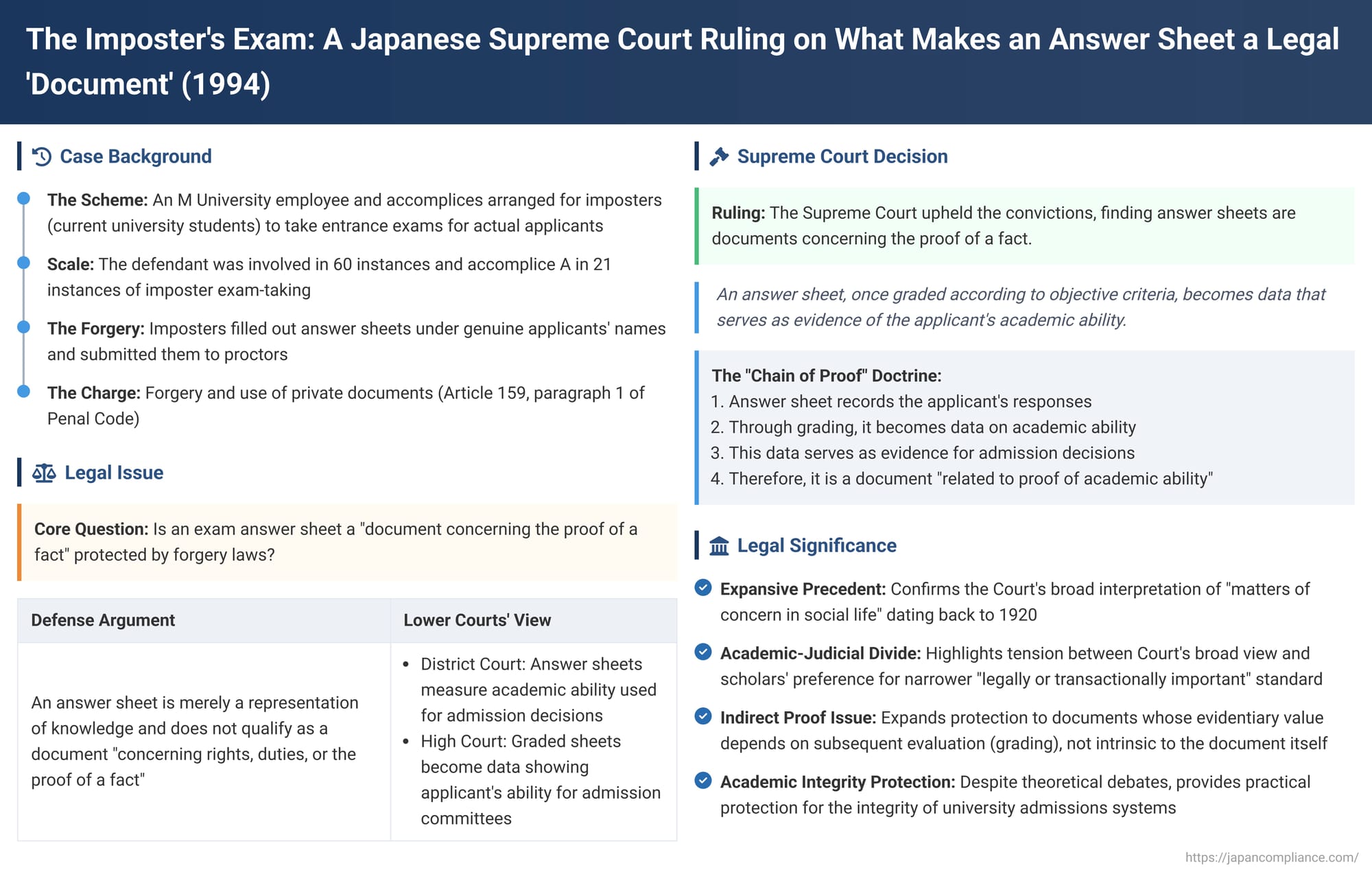

These novel questions were addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on November 29, 1994. The ruling, stemming from a large-scale imposter scandal at a university, delved into the legal definition of a "document" and set a crucial precedent for the application of forgery laws in academic contexts.

The Facts: The M University Scandal

The case involved a sophisticated criminal enterprise orchestrated by an employee of M University, the defendant, along with an accomplice, A.

- The Scheme: They conspired with a third party, B, to arrange for imposters, who were current university students, to take the entrance examinations for M University on behalf of actual applicants.

- The Scale: The operation was extensive. The defendant was personally involved in 60 instances of imposter exam-taking, while accomplice A was involved in 21 instances.

- The Act of Forgery: In each instance, the imposter would sit for the exam, fill out the answer sheet, and submit it to the exam proctor under the name of the genuine applicant. This act of creating and submitting a fraudulent answer sheet was prosecuted as the forgery and use of a private document.

The Legal Crux: Is an Answer Sheet a "Document Concerning the Proof of a Fact"?

The defense's case rested on a foundational challenge to the charge itself. The crime of Forgery of a Private Document (Article 159, paragraph 1 of the Penal Code) is not a general offense; it applies only to documents concerning "rights, duties, or the proof of a fact" (jijitsu shōmei ni kan suru bunsho). The defense argued that a mere exam answer sheet, representing a person's knowledge, did not fit into this protected category.

The lower courts, however, disagreed and convicted the defendants.

- The District Court reasoned that an answer sheet, once graded according to objective criteria, serves to objectively measure the applicant's academic ability. This result is then used to determine admission, a decision that grants the right to enroll. Therefore, the answer sheet proves the fact of what the applicant answered and, by extension, objectively demonstrates their academic ability, making it a document for the proof of a fact.

- The High Court affirmed this, stating that the graded answer sheet becomes data showing the applicant's academic ability, which is then submitted to the faculty committee that makes the admission decision. It concluded that the answer sheets were clearly documents concerning the proof of facts that have significant meaning in social life.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The "Chain of Proof" Doctrine

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, articulating a "chain of proof" logic that has become the decision's key takeaway. The Court acknowledged that an exam answer sheet, in its raw form, "does not itself reveal the applicant's academic ability." However, it reasoned that the answer sheet is the indispensable first link in a critical evidentiary chain:

- The answer sheet is created as a record of the applicant's responses.

- It is then subjected to the process of grading.

- The result of this grading becomes the data that serves as evidence of the applicant's academic ability.

- This evidence of academic ability is then used as the basis for the faculty's decision on whether to grant admission.

Therefore, the Court concluded, because the answer sheet is the essential foundation of this process, it is legally considered a document "related to the proof of an applicant's academic ability." As such, it falls under the broad category of a document that proves a "matter of concern in social life" and is protected by forgery laws.

Analysis: A Broad Definition and a Scholarly Debate

The Supreme Court's decision rests on a very broad interpretation of what constitutes a "document concerning the proof of a fact."

- Expansive Precedent: The Court's reference to a "matter of concern in social life" draws on a long line of precedents that have defined this category expansively. A 1920 decision by its predecessor court declared that any matter of concern in "our real social life" was sufficient, and a 1958 Supreme Court decision applied this standard to an advertisement in a political party's newspaper.

- The Academic Counterpoint: While the Court has consistently favored this broad definition, many legal scholars argue for a more limited interpretation to avoid over-criminalization. They contend that the category should be restricted to documents with a level of importance comparable to those concerning rights and duties, such as those that are "legally or transactionally important."

- The Problem with "Proof": The most sophisticated critique of the Supreme Court's ruling centers on the nature of the proof itself. Does the answer sheet, on its own, actually prove anything of social importance? Its evidentiary value is not intrinsic; it is only created by the external and subsequent act of grading. Critics argue that protecting a document whose meaning is not self-contained but depends on a future process stretches the definition of a "document concerning the proof of a fact" too far. This logic could potentially be extended to criminalize the forgery of personal essays, drafts, or other materials that merely form the "basis" for a later evaluation, an outcome many find troubling.

Despite these theoretical concerns, most legal scholars agree with the ultimate conclusion in this specific case: that a university entrance exam answer sheet warrants protection under forgery laws due to its critical role in the admissions process.

Conclusion

The 1994 "Imposter Exam" ruling is a landmark decision that affirmed the application of forgery laws to the academic sphere. By articulating its "chain of proof" doctrine, the Supreme Court established that a document need not directly prove a socially important fact on its own to be protected. If it is the essential first step in a formal process that culminates in such a proof—like the granting or denial of university admission—it falls within the ambit of the law. The decision reflects a pragmatic choice by the judiciary to prioritize the integrity of vital social systems, even if it required adopting a broad and theoretically challenging interpretation of what constitutes a "document concerning the proof of a fact."