The Imposter Passenger: A Japanese Ruling on Fraud without Financial Loss

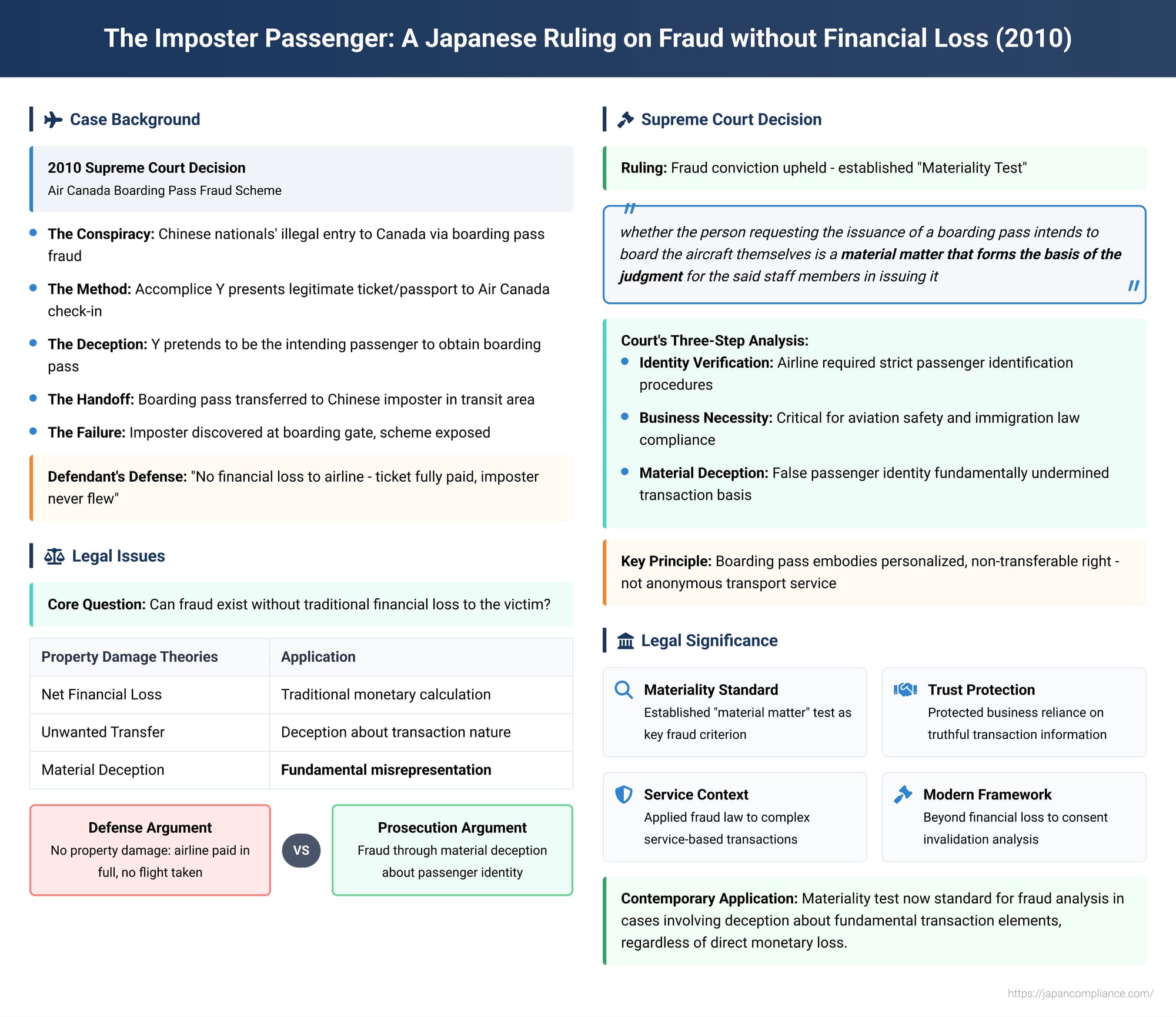

Can you commit fraud if your victim doesn't lose any money? Imagine a person uses a clever lie to obtain a service or a valuable document from a company. The company has been paid in full, and in the end, it suffers no direct financial loss. Has a crime been committed? This question, which tests the very definition of "property damage" in fraud law, was the subject of a major ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 29, 2010.

The case, involving an elaborate scheme to use an "imposter passenger" to get a boarding pass for an international flight, saw the Court move beyond a simple calculation of financial loss. Instead, it focused on whether the deception concerned a "material matter" that was fundamental to the victim's decision to hand over their property. The ruling provides a key insight into the modern understanding of fraud in Japan.

The Facts: The Boarding Pass Swap Scheme

The case centered on a conspiracy to help Chinese nationals enter Canada illegally. The defendant, X, and his accomplices devised a plan to fraudulently obtain a boarding pass for an Air Canada flight departing from Japan's Kansai International Airport bound for Vancouver.

The scheme worked as follows:

- An accomplice, Y, held a legitimate ticket and passport for the flight.

- Y would approach the Air Canada check-in counter and present his ticket and passport to the airline agent, pretending that he was the one who intended to fly.

- His true intention, however, was to obtain the boarding pass, go through security, and then hand it off to a Chinese national waiting in the international transit area.

- The Chinese national would then use the boarding pass, which was in Y's name, to board the plane as an imposter.

The plan was put into action, and the airline agent, deceived into believing Y was the genuine passenger, issued the boarding pass. The plot ultimately failed, however, when the imposter was discovered by staff at the boarding gate.

The defendant and his accomplices were charged with fraud. Their defense was simple: the airline had been paid in full for the ticket, and since the imposter never actually boarded the plane and took the flight, the airline suffered no financial loss. They argued that with no property damage, there could be no crime of fraud.

The Legal Question: Redefining "Property Damage" in Fraud

The defense's argument highlighted a long-standing debate in Japanese fraud law. Because fraud is a property crime, the courts have generally required some form of "property damage" for a conviction. However, what constitutes "damage" has been a matter of theoretical contention. While some theories focus on a victim's net financial loss, a more dominant view in Japanese case law has held that the very act of being tricked into handing over property can be sufficient damage, especially if the victim did not receive what they truly bargained for. This case presented the Supreme Court with an opportunity to clarify and modernize this principle.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The "Materiality" Test

The Supreme Court upheld the fraud conviction, rejecting the defense's "no financial loss" argument. The Court's reasoning did not focus on calculating the airline's monetary loss but instead centered on the materiality of the information that was concealed.

The Court first carefully established the facts surrounding the airline's procedures. It noted that airline agents were required to perform strict identity verification, comparing the passenger's face with their passport photo and ensuring the names on the passport and ticket matched. This was not an arbitrary or trivial step.

The Court then explained why this identity check was so important to the airline's business. It was crucial for two main reasons:

- Aviation Safety: Allowing an unknown, unverified person to board a plane posed a "grave risk to the safety of the aircraft's operation".

- Immigration Law Compliance: The airline was "obligated by the Canadian government to appropriately issue boarding passes to prevent illegal immigration" and faced potential penalties for failing to do so.

Because of these factors, the Court found that ensuring the ticketed passenger was the one actually boarding was a matter of "material importance to the management of the airline's air transport business".

Having established the importance of the passenger's identity, the Court announced its core legal conclusion:

"it must be said that whether the person requesting the issuance of a boarding pass intends to board the aircraft themselves is a material matter that forms the basis of the judgment for the said staff members in issuing it".

Because the defendants lied about a matter so fundamental to the airline's decision-making process, their act was "none other than a deceptive act" under the fraud statute. Obtaining the boarding pass through this material deception was, therefore, a completed act of fraud.

Analysis: From Financial Loss to a Betrayal of Trust

This 2010 decision represents a significant evolution in Japanese fraud jurisprudence, solidifying a shift in focus from a narrow calculation of monetary damage to a broader assessment of the "materiality" of the deception. The key question is no longer simply "Did the victim lose money?" but rather, "Was the victim deceived about a matter so fundamental that it invalidated their consent to the transaction?"

In this case, the airline's service contract was not merely to transport one anonymous person from Point A to Point B. It was to transport the specific, identified individual named on the ticket. The boarding pass, therefore, was not just a piece of paper; it was a valuable piece of property embodying a highly personalized and non-transferable right to board that specific flight. By deceiving the airline about who would ultimately use that right, the defendants fraudulently obtained this valuable property.

The ruling also touches on the interesting intersection of private business interests and public policy. The reason the passenger's identity was so "material" to the airline's business was inextricably linked to public policy concerns like aviation safety and immigration control. The commentary on the case notes that when a business transaction is constrained by such public regulations, deceiving a party about compliance can constitute fraud because the victim's "true intent" is to engage in a lawful and compliant transaction. The defendants' deception betrayed this fundamental basis of the exchange.

Conclusion: The Modern Face of Fraud

The 2010 Supreme Court decision in the "imposter passenger" case provides a clear and modern framework for analyzing fraud in complex service-based transactions where traditional financial loss may not be apparent. It cements the "materiality test" as a key standard in Japanese law.

The ruling's enduring legacy is its principle that a lie becomes a criminal deception when it concerns a matter that is fundamental to the victim's decision to part with their property or provide a service. It affirms that the crime of fraud protects not only the accounting value of property but also the right of individuals and businesses to engage in transactions based on truthful information about matters they deem essential to the bargain.