The Imposter Chairman: Japan's Landmark Case on Corporate Document Forgery

In the worlds of business and governance, the authority to speak for an organization is a powerful and heavily guarded trust. Documents signed by a CEO, a board secretary, or a designated representative bind the entire entity, and public confidence in the authenticity of these documents is essential for commerce and administration to function. But what happens when this trust is violated? If an individual who lacks the proper authority creates official-looking minutes for a board meeting they claim to represent, who is the legal "author" of that fraudulent document? Is it the individual who physically signed it, or the organization they falsely claimed to represent?

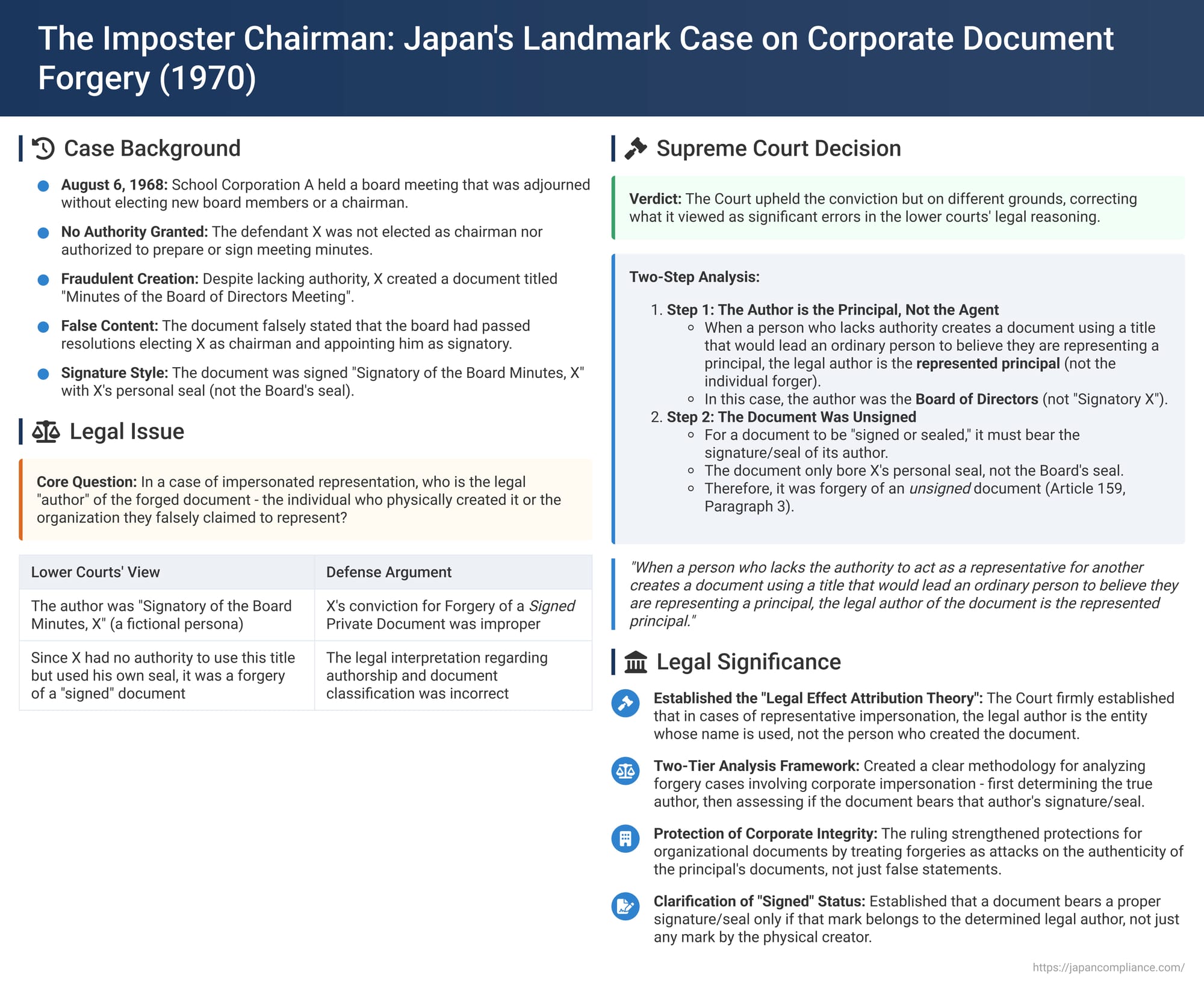

This fundamental question of authorship in the context of corporate representation was definitively answered by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on September 4, 1970. The case, involving a contentious struggle for control of a school corporation, established the guiding principles for how Japanese law treats the crime of forgery by a fake representative.

The Facts: The Phantom Board Resolution

The case arose from a board of directors meeting at a private educational institution, School Corporation A.

- A Meeting Without a Conclusion: A meeting was held on August 6, 1968, to address the appointment of board members and the election of a new chairman. However, the meeting was adjourned without any conclusion being reached on these critical issues.

- An Unauthorized Act: Specifically, the board did not elect the defendant, X, as its chairman, nor did it grant him any authority to prepare or sign the official minutes of the meeting.

- The Forged Document: Despite this complete lack of authority, X and his associates, with the intent to use it for official purposes, proceeded to create a document titled "Minutes of the Board of Directors Meeting". This document falsely stated that the board had, in fact, passed resolutions to elect X as chairman and to appoint him as the official signatory for the minutes.

- The Signature: At the end of this fraudulent document, it was signed not with the seal of the Board of Directors, but with the inscription "Signatory of the Board Minutes, X," followed by X's own personal seal.

The Legal Dispute: Identifying the Author

The lower courts convicted X of the crime of Forgery of a Signed Private Document (Article 159, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code). Their reasoning was that the legal author (meigi-nin) of the document was the fictional persona of the "Signatory of the Board Minutes, X". Since X had no authority to use this title, and since his own seal was used, they concluded it was a forgery of a "signed" document. The defense appealed, challenging this interpretation.

The Supreme Court's Authoritative Ruling

The Supreme Court agreed with the ultimate conclusion that a forgery had been committed and upheld the conviction, but it did so on entirely different legal grounds, correcting what it saw as significant errors in the lower courts' reasoning. The Court's decision established a clear, two-step analysis for such cases.

Step 1: The Author is the Principal, Not the Agent

The Court first established a clear rule for identifying the author in cases of impersonated representation.

- When a person who lacks the authority to act as a representative for another creates a document using a title that would lead an ordinary person to believe they are representing a principal, the document is one whose effects are formally attributed to that principal.

- Therefore, the legal author of the document is the represented principal, not the individual forger who actually signed it.

- In this case, the document's title and content made it clear that it was intended to be the official minutes of the Board of Directors of School Corporation A. The title "Signatory of the Board Minutes" was a credential sufficient to make an ordinary person believe that X was acting on behalf of the Board.

- The Supreme Court thus concluded that X had forged a document in the name of the Board of Directors. The lower courts were mistaken in identifying the author as the fictional "Signatory of the Board Minutes, X".

Step 2: The Document Was Unsigned

Having established the "Board" as the true legal author, the Court then addressed whether the document was "signed or sealed" as required for the more serious version of the crime under Article 159, Paragraph 1.

- For a document to be considered "signed or sealed" by its author, it must bear the signature or seal of that specific author.

- In this case, the document did not have the signature or seal of the Board of Directors of School Corporation A. It only bore the personal seal of the defendant, X.

- Therefore, the Court concluded, the crime committed was not the forgery of a signed document, but the forgery of an unsigned document under Article 159, Paragraph 3, which is a lesser offense.

While the Court found that the lower courts had erred on both of these key legal points, it ultimately upheld the conviction because the defendant's actions still constituted the lesser crime of unsigned document forgery, and since he was convicted of other serious crimes, the sentencing outcome was not affected.

Analysis: Competing Theories of Forgery

The Supreme Court's decision firmly established the "Legal Effect Attribution Theory" in cases of representative impersonation. This theory identifies the author by looking at who the document's legal effects are intended to bind—in this case, the School Corporation's Board of Directors. This approach, however, is just one of several competing legal theories.

- Intangible Forgery View: This minority view would argue that X was the true author, and his false claim of authority was merely false content. Under Japan's formalist system, which primarily punishes the forgery of authorship rather than content for private documents, this would likely mean no crime was committed, a result widely seen as inadequate.

- Combined Personality View: This view, similar to the lower courts' reasoning, suggests the author is a new, combined persona: "X, in his capacity as Representative". It argues that public trust is placed in the qualification itself, and impersonating that qualified status is the essence of the forgery.

- Responsibility Theory: This alternative scholarly view reaches the same conclusion as the Supreme Court but through different reasoning. It asks who the ultimate subject of responsibility for the document is. A person receiving the minutes would hold the Board of Directors, not X personally, responsible for their content; therefore, the Board is the legal author.

Conclusion

The 1970 ruling in the "Imposter Chairman" case remains the authoritative precedent for analyzing forgeries involving the impersonation of representative authority. It provides a clear and enduring framework:

- In cases of false representation, the legal author of the document is the principal or organization being represented, not the individual forger. The crime is an attack on the authenticity of the principal's documents.

- For such a forgery to be considered "signed or sealed," it must bear the actual signature or seal of the principal, not just the personal seal of the forger.

This decision is essential for understanding how the law protects the integrity of corporate and organizational acts. It ensures that those who would usurp the authority of an organization to create fraudulent documents are held accountable for forging the documents of the very entity they falsely claim to represent.