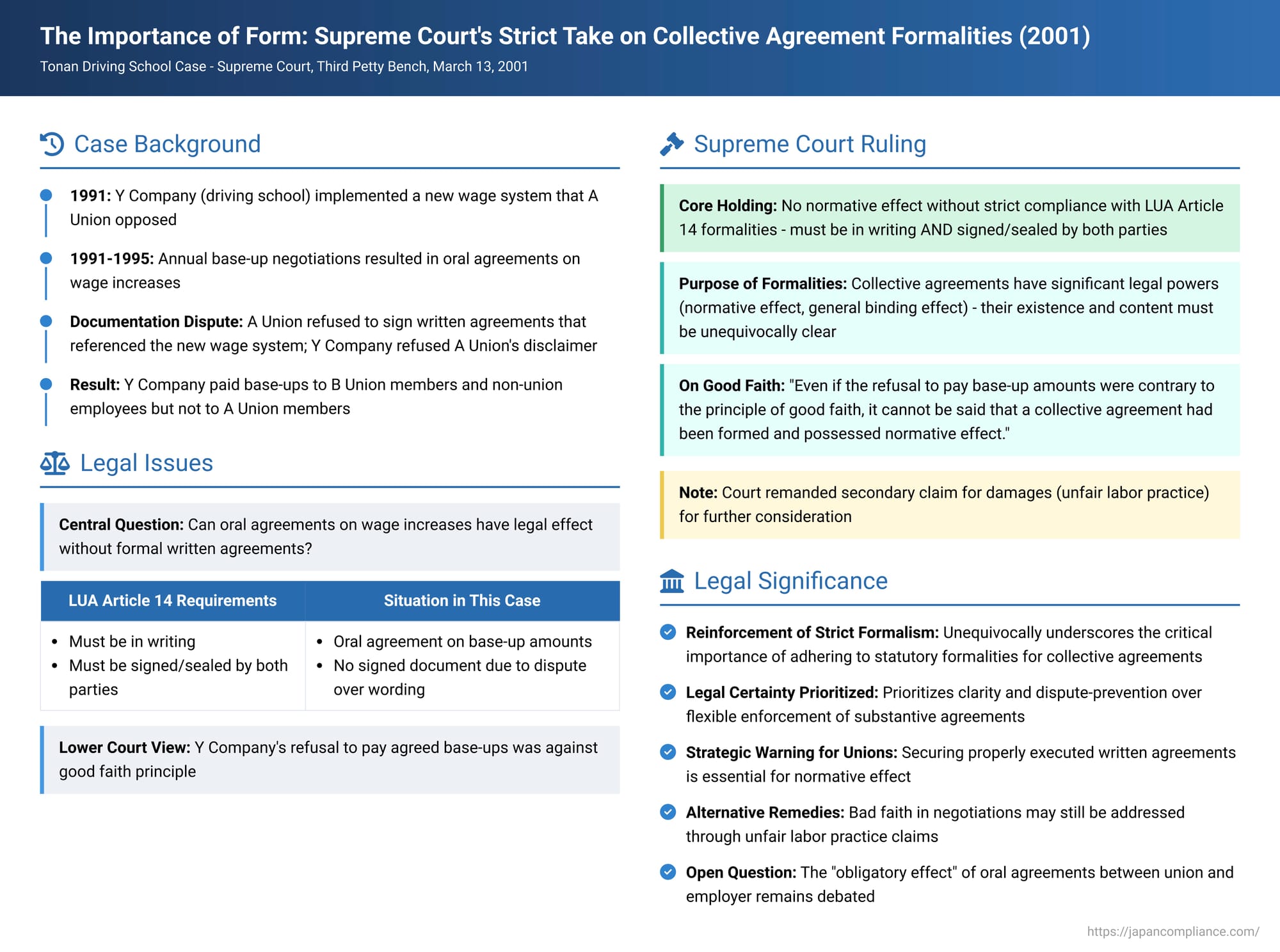

The Importance of Form: Supreme Court's Strict Take on Collective Agreement Formalities in the Tonan Driving School Case

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of March 13, 2001 (Case No. 2000 (Ju) No. 192: Claim for Wages, etc.)

Appellant (Employer): Y Company (operating a driving school)

Appellees (Employees): X (and others)

Collective bargaining agreements are a cornerstone of labor relations, providing stability and defining terms of employment. In Japan, the Labor Union Act (LUA) grants these agreements significant legal power, including the "normative effect" which allows their terms to directly shape individual employment contracts. However, LUA Article 14 stipulates formal requirements for a collective agreement to take effect: it must be in writing and signed or sealed by both the employer and the union. The Supreme Court's judgment on March 13, 2001, in the Tonan Driving School case, critically underscored the strict necessity of these formalities, even when parties appear to have reached an oral understanding on specific issues.

The Sticking Point: Facts of the Dispute

The case involved Y Company, the operator of a driving school, and its employees, X, who were members of A Union. Historically, Y Company and A Union had engaged in annual negotiations for base wage increases (bēsu appu), and wages were paid based on the resulting collective agreements.

The dispute began in April 1991 when Y Company proposed a comprehensive revision of its wage system. A Union did not consent to this new system. Despite A Union's opposition (a formal letter of which was attached), Y Company proceeded to implement the new wage system in August 1991 by revising its work rules and filing them with the relevant Labor Standards Inspection Office. Thereafter, Y Company began paying all employees, including members of A Union like X, according to this new wage structure.

The core of the conflict arose during the annual base-up negotiations from fiscal year 1991 through fiscal year 1995:

- Fiscal Year 1991:

- Y Company offered A Union a ¥5,000 base-up. However, this offer was explicitly premised on the new wage system already implemented by the company (i.e., the starting salary under the new system of ¥135,000 would be increased by ¥5,000). Y Company presented a draft written agreement reflecting this.

- A Union agreed to the ¥5,000 amount of the increase. However, concerned that signing the company's draft agreement would imply their acceptance of the new wage system they had opposed, A Union proposed signing the agreement only if a separate memorandum could be attached. This memorandum would clarify that their agreement to the base-up amount did not constitute an endorsement of the new wage system itself.

- Y Company refused to allow the attachment of such a memorandum.

- A Union, believing that signing the agreement as drafted by Y Company (without the clarifying memorandum) would be tantamount to de facto acknowledging and accepting the new wage system, refused to sign the formal agreement.

- Consequently, because no written collective agreement for the base-up was finalized with A Union, Y Company did not pay the ¥5,000 base-up to the members of A Union. However, Y Company did pay the base-up to members of B Union (another union at the company, named Tonan-kai in the judgment, which had consented to the new wage system) and to non-unionized employees.

- Fiscal Years 1992 through 1995:

- A similar pattern unfolded each year. The parties would negotiate and reach an understanding on the specific monetary amount of the base-up (these understandings are collectively referred to in the judgment as "the present agreements" - honken kaku gōi).

- However, Y Company consistently insisted that any formal written agreement must reference the new wage system's starting salary as the basis for the increase. A Union, equally consistently, refused to sign any such document without its disclaimer regarding the new wage system, fearing it would undermine their opposition to it.

- As a result, no formal, signed written collective agreement on the base-ups was concluded between Y Company and A Union for these years. Y Company continued its practice of paying the base-up amounts only to B Union members and non-union employees, while withholding it from A Union members.

Aggrieved by this, X (the members of A Union) filed a lawsuit against Y Company, primarily seeking payment of the unpaid wages corresponding to the base-up amounts they believed had been agreed upon during the negotiations for fiscal years 1991-1995. They also lodged a secondary claim for damages, likely on the grounds of tort (e.g., alleging Y Company's conduct constituted an unfair labor practice).

Lower Courts' Approach: Finding Ways to Uphold the Wage Claim

The First Instance court (Yokohama District Court, June 13, 1996) largely found in favor of X, granting their wage claims.

The High Court (Tokyo High Court, November 22, 1999) also ruled substantially in favor of X, although its reasoning differed. The High Court acknowledged the lack of a formally executed written agreement. However, it found that Y Company's refusal to pay the agreed-upon base-up amounts to A Union members, merely because a written agreement had not been finalized under the circumstances (where Y Company insisted on terms A Union could not accept without compromising its stance on the new wage system), constituted a breach of the principle of good faith. Based on this, the High Court effectively held that the oral agreements on the base-up amounts should be treated as if they had the normative effect of a formal collective agreement, thus obligating Y Company to pay. Y Company appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Strict Adherence to Formalities

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 13, 2001, reversed the High Court's decision regarding X's primary claim for unpaid wages based on a normatively effective collective agreement. It held that the lack of a formally executed written agreement was fatal to this claim.

1. The Purpose and Significance of LUA Article 14's Formal Requirements:

The Court began by elaborating on the rationale behind LUA Article 14, which mandates that a collective agreement must be in writing and bear the signatures or names and seals of both parties to take effect.

- Collective agreements are the culmination of often complex and adversarial negotiations between labor and management, covering a variety of interrelated matters. They play a crucial role in stabilizing labor relations for a defined period.

- Recognizing this important function, the Labor Union Act grants collective agreements significant legal powers:

- Normative Effect (LUA Article 16): The standards concerning working conditions and treatment of workers set forth in a collective agreement directly regulate the content of individual labor contracts between the employer and union members (and potentially other employees under certain conditions).

- General Binding Effect (LUA Article 17): Under specific circumstances (e.g., when a collective agreement covers a substantial majority of similar workers in a locality), its terms can be extended to cover non-union workers in the same region.

- The Labor Standards Act (Article 92) also stipulates that work rules must not contravene any applicable collective agreement.

- The Supreme Court reasoned that because the law bestows such powerful legal effects upon collective agreements, their existence and content must be unequivocally clear. The formal requirements of LUA Article 14 – a written document signed or sealed by both parties – serve precisely this purpose. Given that collective agreements arise from intricate negotiation processes, relying on mere oral agreements or inadequately formalized writings would invite disputes regarding the existence, nature, and scope of the consensus reached. The statutory formalities aim to prevent such unnecessary conflicts by demanding that the final, settled agreement is clearly manifested in its very form.

2. No Normative Effect Without Strict Compliance with Formalities:

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court reached a clear and stringent conclusion:

- Unless an agreement between a labor union and an employer is documented in writing AND bears the signatures or names and seals of both parties, it cannot be granted the normative effect of a collective agreement as envisioned by the Labor Union Act. This holds true even if there is evidence that an oral agreement or a meeting of minds on particular terms (such as the amount of a wage increase) had occurred.

3. Employer's Bad Faith Does Not Create a Formal Collective Agreement:

The Supreme Court directly addressed and rejected the High Court's rationale that Y Company's alleged breach of good faith (in its stance during the finalization of the written agreement) could effectively bypass the formal requirements of LUA Article 14 and lead to a de facto normative collective agreement. The Supreme Court stated: "Even if the [company's] refusal to pay the base-up amounts for the reason that a written agreement had not been created were contrary to the principle of good faith, it cannot be said that a collective agreement had been formed and possessed normative effect." The formal prerequisites are absolute for the attachment of such strong legal consequences.

4. No Independent, Enforceable Agreement on Just the Base-Up Amount for A Union:

The Court further analyzed the nature of "the present agreements" on the base-up amounts. It found that these understandings on the monetary figures were reached with the implicit assumption that they would be implemented only after being incorporated into a properly formalized written collective agreement.

- The negotiations involved not just the base-up amount but also the contentious issue of how the agreement would be worded, particularly concerning its relation to the new wage system. A Union's refusal to sign Y Company's drafts (which referenced the new system) and Y Company's refusal to accept A Union's proposed caveats meant that the overall negotiations for a finalized collective agreement for A Union members had, in effect, broken down or "run aground" (tonza shita).

- Given this breakdown over the form and underlying premises of the written agreement, the Supreme Court concluded that it was not possible to isolate the agreement on the base-up amount and find that Y Company had an independent obligation to pay this amount to A Union members. The entire package deal, including the formal written document, had not materialized for A Union.

- The fact that Y Company had paid the base-up to B Union members and non-union employees (who had accepted the new wage system or were not covered by A Union's specific dispute), or that Y Company might have paid a base-up without a formal agreement in one past instance (fiscal year 1983), did not alter the legal reality concerning A Union for the fiscal years 1991-1995.

Distinction Between Contractual Claims and Unfair Labor Practices

While X's primary claim for unpaid wages—premised on the existence of a normatively effective collective agreement—failed due to the lack of statutory formalities, the Supreme Court did not entirely close the door on potential remedies. It remanded X's secondary claim for damages (based on tort/unfair labor practice) to the Tokyo High Court for further consideration.

This act of remanding the secondary claim is significant. It indicates that while the absence of a formal collective agreement prevents direct enforcement of its purported terms, the conduct of the employer during the negotiation process or its differential treatment of union members could still be subject to legal scrutiny under unfair labor practice provisions or general tort law. The PDF commentary highlights this as a separation between "issues of the negotiation process (and the parties' conduct therein)" and "the issue of the formal requirements of LUA Article 14 for a concluded agreement."

Significance and Implications of the Judgment

The Tonan Driving School Supreme Court decision has had a lasting impact on the understanding and practice of collective bargaining in Japan:

- Reinforcement of Strict Formalism for Collective Agreements: The judgment unequivocally underscores the critical importance of adhering to the statutory formalities (a written document signed or sealed by both parties) if a labor-management agreement is to be accorded the powerful normative effect under the Labor Union Act. Oral understandings or unsigned drafts, however clear they might seem on specific points, will not suffice to create directly enforceable changes to individual employment contracts via this mechanism.

- Prioritization of Legal Clarity: The ruling prioritizes the legal certainty and dispute-prevention functions that the formal requirements of LUA Article 14 are designed to serve. This preference for clarity can sometimes come at the expense of a more flexible approach that might look to the substantive agreement reached by the parties, especially in situations where one party's conduct regarding formalization is seen as problematic.

- Strategic Considerations for Unions: This decision serves as a clear reminder to labor unions that securing a properly executed written collective agreement is essential if they wish to ensure that agreed-upon terms have normative effect and are directly enforceable as employment conditions. Relying on informal understandings or employer promises without this formalization carries significant risks.

- Availability of Alternative Remedies (e.g., Unfair Labor Practice Claims): The remand of the secondary claim for damages suggests that even if a collective agreement is not successfully formalized due to an employer's negotiation tactics, unions and their members may still have recourse through other legal channels, such as filing unfair labor practice complaints (e.g., for bad-faith bargaining or discriminatory treatment).

- The Unaddressed Question of "Obligatory Effect": The PDF commentary points out an important nuance: the Supreme Court, in this particular case, primarily addressed the normative effect of the purported agreements. Because it found that there was no conclusive agreement on the implementation of the base-up for A Union members without the formal document, it did not explicitly need to rule on whether an oral agreement, lacking LUA Article 14 formalities, could still have "obligatory effect" (債務的効力 - saimuteki kōryoku). This refers to the contractual binding force of an agreement between the union and the employer themselves, as distinct from its power to alter individual employment contracts. This question remains a subject of ongoing academic debate in Japan. Some scholars argue that even without full LUA Article 14 compliance, a clear agreement might create contractual obligations between the signatory parties (the union and the employer), while others maintain that the lack of formalities vitiates any legal effect, whether normative or merely obligatory.

Conclusion

The Tonan Driving School Supreme Court judgment is a critical precedent in Japanese labor law, firmly establishing that the significant legal powers of a collective agreement, particularly its ability to directly set and alter terms of individual employment contracts (normative effect), are contingent upon strict adherence to the statutory requirements of being in writing and duly signed or sealed by both the union and the employer. While this emphasis on formalism might seem rigid, especially in contexts where substantive agreement on certain terms appears to have been reached, the Court prioritized the legislative intent of ensuring clarity and preventing disputes over these powerful instruments of labor relations. The decision also implicitly directs parties to address issues of bad faith or misconduct in the negotiation process itself through other legal avenues, such as unfair labor practice proceedings, rather than by attempting to confer normative status on informal or incomplete agreements.