The Hotel N Fire: A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Corporate Executive Liability

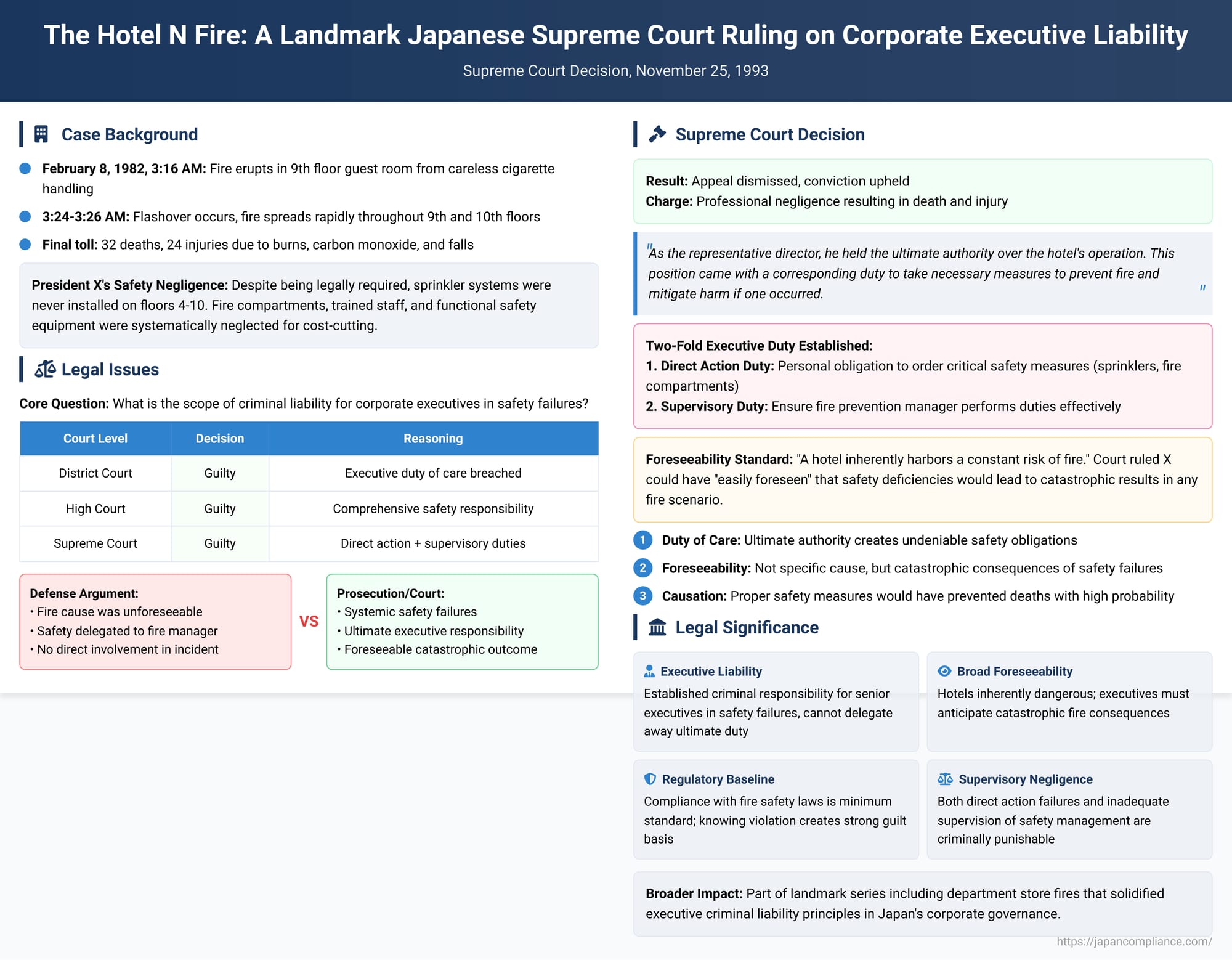

On November 25, 1993, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a final, decisive judgment in a case that has since become a cornerstone of Japanese law concerning corporate and executive responsibility. The case involved a catastrophic fire at a major hotel in Tokyo, resulting in the tragic deaths of 32 people and injuries to 24 others. The court upheld the criminal conviction of the hotel's president and representative director for professional negligence resulting in death and injury.

This decision is not merely about a single tragic incident; it provides a profound insight into the legal framework in Japan for holding senior executives accountable for safety failures within their organizations. The court’s detailed reasoning illuminates the concepts of duty of care, foreseeability, and supervisory negligence as they apply to those at the highest levels of corporate leadership.

Factual Background: The Incident

The structure in question, Hotel N, was a massive and complex building with a Y-shaped design, comprising two basement floors, ten stories above ground, and a four-story tower. At the time of the fire, it had approximately 420 guest rooms and a capacity of around 782 guests.

In the early morning hours of February 8, 1982, at approximately 3:16 AM, a fire broke out in a guest room on the 9th floor, started by a guest's careless handling of a cigarette. An on-duty employee who discovered the fire attempted to use a fire extinguisher. While this momentarily suppressed the flames on the bed's surface, the fire reignited about a minute later. Because the guest room door had been left open, the fire rapidly intensified. Between 3:24 AM and 3:26 AM, a flashover occurred in the room and the adjacent hallway. This phenomenon repeated, causing the fire and toxic smoke to spread with terrifying speed throughout the 9th and 10th floors via hallways, ceiling cavities, and utility shafts.

Although the fire was discovered relatively early by hotel staff, the response was chaotic and ineffective. There was no organized, team-based reaction. The staff, lacking proper training and a clear command structure, failed to take effective individual actions. Initial firefighting efforts were inadequate, very few warnings were given to guests on the fire-affected floors, and evacuation guidance was almost non-existent. No one thought to manually operate the main fire alarm or close the fire doors. The call to the fire department was also significantly delayed.

The consequences were devastating. Guests, many of whom were asleep and unfamiliar with the building's complex layout, were trapped. They were overcome by the intense flames and thick smoke or were forced to jump from windows. The final toll was 32 fatalities from burns, carbon monoxide poisoning, and fall-related injuries, with another 24 people suffering injuries ranging from minor to severe.

The Defendant and a Pattern of Systemic Safety Failures

The defendant in the case, identified as X, was the President and Representative Director of Company N, the entity that owned and operated Hotel N. Appointed in May 1979, he held the ultimate authority and responsibility for all aspects of the hotel's management and operations. This included overseeing all employees, managing building renovations and maintenance, and ensuring the implementation of all safety measures, including fire prevention. Under Japan’s Fire Service Act, he was legally designated as the "person with title to manage" the property.

Another key figure was A, the hotel's general manager and head of general affairs. A was formally appointed as the statutory fire prevention manager, tasked with the day-to-day execution of fire safety duties under the supervision of X.

The investigation and subsequent trials revealed that the tragic outcome of the fire was not merely a matter of bad luck or a slow response. It was the direct result of years of systemic neglect and a deliberate disregard for safety, driven by the defendant's management policies. The hotel was a catastrophe waiting to happen, with numerous, well-documented deficiencies:

- Lack of Sprinkler Systems: Under regulations enacted in 1974, the hotel was required to retrofit nearly the entire building with a sprinkler system by March 31, 1979. This was never done for the 4th through 10th floors. X was fully aware of this non-compliance from the time he became president.

- Absence of Fire Compartments: The law allowed for the installation of "alternative fire compartments" in lieu of sprinklers. These compartments, built with fire-resistant walls, floors, and automated fire doors, are designed to contain a fire within a small area. Apart from some sections on the 4th and 7th floors, these crucial safety features were also missing.

- Hazardous Interior Construction: The walls and ceilings of guest rooms and hallways were finished with flammable materials like plywood and combustible wallpaper. Many guest room doors were simple wood. Worse, numerous unsealed openings and gaps existed in walls between rooms, in partitions, and around pipes, creating pathways for fire and smoke to travel unimpeded.

- Dysfunctional Safety Equipment: X had implemented an extreme cost-cutting policy that required his personal approval for even minor expenditures. As a result, regular professional maintenance of critical safety equipment was neglected. Many fire doors failed to close automatically as designed, and portions of the emergency broadcast system were broken and unusable.

- Inadequate Staffing and Training: The company had drastically reduced its workforce. However, the legally required fire safety plan and the internal fire brigade organization were never updated to reflect these changes. After X took over as president, virtually no meaningful fire drills—encompassing firefighting, emergency communication, and evacuation—were conducted. A single, purely formal drill was held in October 1981 only after repeated demands from the fire department.

Fire authorities conducted inspections approximately every six months. On each occasion, they pointed out the same critical issues to the hotel’s management, including A: the lack of retrofitting, the non-functional fire doors, the structural deficiencies, the outdated safety plan, and the absence of training. From July 1979 onwards, the authorities issued monthly directives urging the completion of the legally mandated retrofitting.

X was kept fully informed of these official warnings and received reports from A. Despite this, and despite the company having sufficient funds to perform the necessary work, he persisted in a management approach that prioritized profit over safety, allowing the dangerous conditions to fester.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The case proceeded through the Japanese court system, with both the district court and the high court finding X guilty of professional negligence resulting in death and injury. X appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal and affirmed the lower courts' verdicts. Its written decision provides a masterclass in the application of negligence principles to a corporate executive. The court methodically dismantled the defense's arguments by focusing on three core legal concepts: Duty of Care, Foreseeability, and Causation/Avoidability.

1. The Executive's Duty of Care (注意義務)

The court began by unequivocally establishing X’s duty of care. As the representative director, he held the ultimate and de facto power over the hotel's entire operation. This position of supreme authority came with a corresponding and undeniable duty to take necessary measures to prevent a fire and to mitigate the harm if one occurred.

The court articulated a two-fold duty for X, encompassing both direct action and supervision—a concept often referred to as "supervisory negligence" (監督過失).

- Duty of Direct Action: Certain critical safety measures, particularly the large-scale retrofitting of sprinklers or fire compartments, were capital expenditures that fell outside the authority of the fire prevention manager, A. These were strategic decisions requiring executive approval and funding. The court ruled that X had a direct, personal obligation to order and execute these measures.

- Duty of Supervision: While A was the designated fire prevention manager, X was responsible for ensuring that A could, and did, perform his duties effectively. This included supervising A in the creation of a viable fire plan, the organization of regular and realistic fire drills, and the proper maintenance of all fire safety equipment.

The court found that X had comprehensively failed in both aspects of this duty. He did not order the retrofitting he knew was legally required and essential for safety. Furthermore, he was fully aware that A's management of fire safety was deficient—that plans were outdated and training was non-existent—yet he did nothing to rectify the situation or compel A to do so. He simply "allowed the deficiencies in the fire prevention management system to persist."

2. Foreseeability of Harm (予見可能性)

A key element in any negligence case is foreseeability. The defense could argue that the specific cause of the fire—a guest's carelessness—was an unpredictable event. However, the Supreme Court took a much broader view, which has become a standard in Japanese jurisprudence for such cases.

The court ruled that it was not necessary for X to have foreseen the specific cause of the fire. The judgment states: "A hotel, which offers accommodation and other conveniences to a large, unspecified number of people day and night, inherently harbors a constant risk of fire."

The critical foreseeability was not the spark, but the catastrophic result. The court reasoned that X knew about the hotel's profound safety vulnerabilities: the lack of sprinklers, the flammable interiors, the structural gaps, the faulty equipment, and the untrained staff. Given this knowledge, the court concluded that X could have "easily foreseen" that if a fire were to start for any reason, the lack of an effective response would allow it to develop into a major blaze. This would inevitably endanger the lives of guests, who were unfamiliar with the building's layout and escape routes, leading to a high probability of deaths and injuries.

The foreseeability, therefore, was not of a guest dropping a cigarette, but of the deadly consequences that would follow any fire in the death-trap he was managing.

3. Causation and Avoidability (結果回避の可能性)

Finally, the court established a clear and direct causal link between X's negligence and the tragic outcome, a concept known as the "possibility of avoiding the result." The court methodically detailed how the disaster could have been prevented if X had fulfilled his duties.

The judgment presents a compelling counterfactual analysis:

- If Sprinklers Were Installed: Had the legally required sprinkler system been in place, it would have activated as the fire grew in the initial guest room, suppressing the flames and preventing the fire from ever spreading beyond that room.

- If Fire Compartments Existed: Had the alternative fire compartments been constructed, the 9th and 10th floors would have been divided into smaller, fire-resistant cells. The fire would have been contained within a small section of guest rooms. The fire-resistant walls and automated doors would have prevented the flashovers in the hallway and stopped the vertical spread of fire and smoke through utility shafts. This would have preserved the integrity of evacuation routes and bought precious time.

- If Staff Were Trained and Plans Were Sound: On top of these structural measures, if a proper fire safety plan had been established and drilled, the staff's response would have been entirely different. An effective initial firefighting attempt, prompt sounding of alarms, and organized evacuation guidance would have been possible.

The court concluded with certainty that these measures, "taken together," would have had a high probability of avoiding the deaths and injuries. Since there were no circumstances, financial or otherwise, that made it difficult for X to take these actions, his failure to do so was the direct cause of the tragedy. His inaction constituted a breach of his duties, and this breach led directly to the loss of life.

Broader Significance

The Hotel N fire case did not occur in a vacuum. It was the last in a series of major fire-related criminal cases involving large public buildings—including the T Department Store case, the S Department Store case, and the K Prince Hotel case—that solidified the legal principles of executive criminal liability in Japan. These cases collectively established that senior executives, particularly those with ultimate de facto control, cannot insulate themselves from criminal responsibility by delegating safety tasks to subordinates.

The ruling makes clear that compliance with administrative regulations, such as the Fire Service Act, is the baseline for avoiding criminal negligence. A knowing, prolonged, and financially-motivated disregard for such regulations, as seen in this case, forms a powerful basis for a finding of guilt.

The court’s decision establishes that for those in positions of ultimate authority, negligence can be found in their omissions. X was not convicted for starting the fire, but for failing to create and maintain an environment where such a fire, regardless of its origin, could be controlled and its consequences averted. His crime was a failure of governance, a failure of supervision, and a fundamental failure to uphold the duty of care he owed to every single guest who entered his hotel. The 1993 Supreme Court decision ensures that this profound responsibility remains an undeniable legal obligation for corporate leaders in Japan.