The Horiki Litigation: Legislative Discretion and Social Security Benefits in Japan

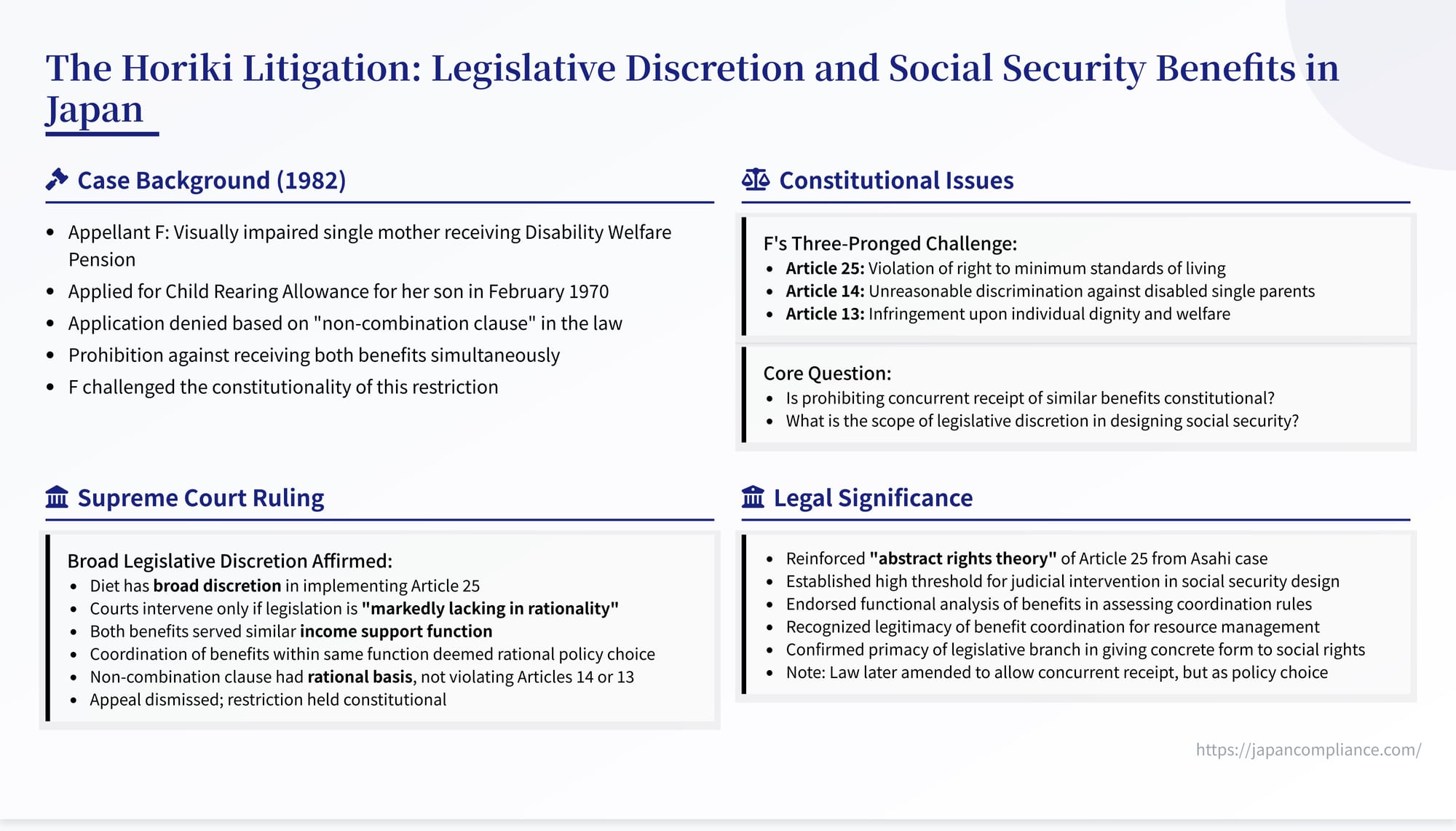

TL;DR: The 1982 Horiki Litigation reaffirmed broad legislative discretion under Article 25, upholding a statutory “non-combination clause” that barred simultaneous receipt of a Disability Welfare Pension and a Child Rearing Allowance. The Supreme Court set a high bar—“markedly lacking in rationality”—for striking down social-security legislation.

Table of Contents

- Background of the Case

- Constitutional Challenges Raised

- Supreme Court Reasoning

- Key Takeaways on Legislative Discretion

- Significance for Japan’s Social Security Framework

Following the landmark Asahi Litigation, the Japanese Supreme Court continued to shape the understanding of constitutional social rights and the role of the judiciary in reviewing social welfare legislation. The 1982 decision by the Grand Bench in the Horiki Litigation (Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Administrative Disposition, etc., Showa 51 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 30) provides crucial insights into the scope of legislative discretion under Article 25 of the Constitution, particularly when dealing with the coordination and potential overlap of different social security benefits. This case specifically addressed the constitutionality of a legal provision that prohibited the concurrent receipt of a Disability Welfare Pension and a Child Rearing Allowance.

Background of the Case

The appellant, F, was a visually impaired individual whose disability corresponded to Grade 1, Item 1 under the appendix to the National Pension Act (国民年金法, Kokumin Nenkin Hō). As such, she was a recipient of a Disability Welfare Pension (障害福祉年金, Shōgai Fukushi Nenkin) provided under that Act. F had a son (born May 12, 1955) from a common-law marriage. After separating from her partner, she raised the child single-handedly.

In February 1970, F applied to the Governor of Hyogo Prefecture (the appellee and defendant) seeking certification of her eligibility for the Child Rearing Allowance (児童扶養手当, Jidō Fuyō Teate) under the Child Rearing Allowance Act (児童扶養手当法, Jidō Fuyō Teate Hō). This allowance is generally aimed at supporting single-parent households.

However, in March 1970, the Governor issued a disposition denying F's application. F filed an administrative objection (an internal appeal) against this decision, but the Governor upheld the denial in June 1970.

The stated reason for the denial was based on a specific provision within the Child Rearing Allowance Act as it existed at that time (specifically, Article 4, Paragraph 3, Item 3, prior to its amendment by Act No. 93 of 1973). This provision, referred to in the judgment as the "non-combination clause" (併給調整条項, heikyū chōsei jōkō), stipulated that an individual was ineligible for the Child Rearing Allowance if they were already receiving a public pension payment, such as the Disability Welfare Pension that F was receiving. In essence, the law prohibited the concurrent payment (heikyū) of these two benefits to the same person.

The Constitutional Challenge

F challenged the Governor's decision in court, ultimately reaching the Supreme Court. Her core arguments centered on the constitutionality of the non-combination clause itself. She contended that this provision violated several fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution of Japan:

- Article 25 (Right to Minimum Standards of Living): F argued that denying her the Child Rearing Allowance simply because she received the Disability Welfare Pension violated her right, and implicitly her child's right, to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living. She essentially claimed that both benefits were necessary to achieve this constitutional standard in her circumstances as a disabled single parent.

- Article 14 (Equality under the Law): F asserted that the non-combination clause created unreasonable discrimination. It treated individuals receiving the Disability Welfare Pension differently from other single parents who were not receiving such a pension, denying the former group access to the Child Rearing Allowance without sufficient justification.

- Article 13 (Respect for the Individual / Right to Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness): F also argued that the provision was arbitrary and unreasonable, infringing upon the dignity of the individual, particularly affecting the well-being of the child being raised.

The lower courts had found the non-combination clause to be constitutional, leading to F's appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court, sitting as the Grand Bench, unanimously dismissed F's appeal, thereby upholding the constitutionality of the non-combination clause. The Court's reasoning addressed each of the constitutional challenges raised.

1. Reasoning on Article 25 (Right to Minimum Standards of Living):

The Court began by reaffirming the interpretation of Article 25 established in the earlier Asahi Litigation and the 1948 precedent it cited.

- Nature of Article 25 Rights: The Court reiterated that Article 25, Paragraph 1 (guaranteeing the right to minimum standards) primarily declares a state duty to manage national affairs towards achieving this goal. Article 25, Paragraph 2 (mandating state efforts in social welfare, social security, and public health) declares the state's responsibility to create and enhance social legislation and facilities. Crucially, these provisions do not directly grant individuals concrete, enforceable rights against the state to demand a specific level of benefit or service. Instead, concrete "living rights" (生活権, seikatsuken) are established and fleshed out through the specific laws and systems created by the state (primarily the Diet) pursuant to its duty under Article 25, Paragraph 2.

- Abstract and Relative Nature of "Minimum Standards": The Court emphasized that the concept of "minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living" is inherently abstract and relative. Its concrete meaning is not fixed but must be determined in relation to the prevailing cultural, economic, and social conditions of the time, as well as the general standard of living among the populace.

- Legislative Discretion: Translating the abstract mandate of Article 25 into concrete legislation requires complex considerations. Lawmakers must inevitably take into account the nation's financial capacity. Furthermore, designing social security systems involves multifaceted, diverse, and highly specialized technical analyses, informed by broader policy judgments. Given these factors, the Court held that the choice and determination of what specific legislative measures to enact in response to Article 25 rests within the broad discretion (広い裁量, hiroi sairyō) of the legislature (the Diet).

- Standard for Judicial Review: Consequently, the judiciary's role in reviewing such legislative choices is limited. Courts should not intervene unless the legislative measure is markedly lacking in rationality (著しく合理性を欠き, ichijirushiku gōrisei o kaki) and must be seen as a clear deviation from or abuse of legislative discretion (明らかに裁量の逸脱・濫用と見ざるをえない, akiraka ni sairyō no itsudatsu/ran'yō to mizara o enai). Matters falling within the realm of legislative policy choices based on such complex considerations are generally considered unsuitable for judicial review, barring such exceptional circumstances.

- Applying the Principles to the Non-Combination Clause: The Court then applied these principles to the specific non-combination clause at issue. It acknowledged that both the Disability Welfare Pension (under the National Pension Act) and the Child Rearing Allowance (under its own Act) were social security systems established with the purpose of realizing the spirit of Article 25. Both involved providing fixed cash payments to individuals meeting certain criteria.

- Characterizing the Benefits: The Court examined the purpose and nature of the two benefits. While acknowledging that the Child Rearing Allowance might have historical connections to the broader concept of child allowances aimed purely at offsetting child-rearing costs, it looked at the overall structure and purpose defined in the relevant statutes (National Pension Act Articles 1, 2, 56, 61; Child Rearing Allowance Act Articles 1, 2, 4). Comparing these, particularly with the Mother-Child Welfare Pension (母子福祉年金, Boshi Fukushi Nenkin) also under the National Pension Act, the Court concluded that the Child Rearing Allowance was most appropriately viewed as a system complementary to the Mother-Child Welfare Pension. It differed in character from the pure child allowance provided under the separate Child Allowance Act (児童手当法, Jidō Teate Hō), which clearly targeted expenses related to child-rearing. Instead, the Court found that the Child Rearing Allowance, like the Mother-Child Welfare Pension and indeed public pensions generally (including the Disability Welfare Pension), fundamentally functioned as income support (所得保障, shotoku hoshō) for the recipient.

- Justification for Coordinating Income Support: The Court reasoned that in social security systems, it is common to face situations where a single individual experiences multiple "contingencies" (事故, jiko) that might qualify them for different benefits (a "multiple contingency" scenario, 複数事故, fukusū jiko). While each contingency (like disability or becoming a single parent) might individually lead to a loss or reduction in earning capacity, the degree of loss doesn't necessarily increase proportionally with the number of contingencies. In such cases, deciding whether to allow the concurrent payment of multiple public pensions or allowances that share a similar character (like income support) involves considerations of overall fairness and resource allocation within the social security system. Such decisions about "combination adjustments" (heikyū chōsei) between public pensions fall squarely within the legislative discretion previously outlined.

- Benefit Levels: The Court also reiterated that the amount of benefits provided under such legislation is also a matter of legislative policy discretion. A benefit level being considered low does not, in itself, automatically lead to a violation of Article 25.

- Conclusion on Article 25: Based on this analysis, the Court concluded that the non-combination clause, which prohibited the concurrent payment of two benefits deemed to be similar in their fundamental character as income support, was a policy choice within the broad discretion of the Diet. It was not markedly irrational or an abuse of that discretion. Therefore, the original judgment finding no violation of Article 25 was correct. The Court explicitly noted that subsequent legislative amendments did eventually allow the concurrent payment of the Child Rearing Allowance with the Disability Welfare Pension (and the Old Age Welfare Pension), but it viewed these amendments as later policy changes made within the Diet's discretionary power, which did not retroactively render the previous non-combination rule unconstitutional.

2. Reasoning on Article 14 (Equality) and Article 13 (Dignity):

Having established the legislative latitude under Article 25, the Court then addressed the claims under Articles 14 and 13.

- Potential for Violation: The Court acknowledged that even legislation enacted pursuant to Article 25 could potentially violate other constitutional guarantees. If such legislation established classifications (regarding eligibility, conditions, benefit amounts, etc.) that constituted unreasonable and unjustifiable discrimination or contained provisions that infringed upon individual dignity, then separate violations of Article 14 or Article 13 could arise.

- Assessing the Discrimination (Article 14): The Court conceded that the non-combination clause resulted in differential treatment between single parents receiving the Disability Welfare Pension (like F) and those not receiving such a pension, concerning their eligibility for the Child Rearing Allowance. However, building upon its analysis under Article 25 (the similar income-support nature of the benefits), and considering points raised by the lower court – particularly the existence of various other policies and measures aimed at supporting individuals with disabilities and single-parent households, as well as the overarching safety net provided by the Public Assistance system itself – the Court found the differentiation was not without a rational basis. It concluded that the discrimination was not unreasonable or unjust to the point of violating the equality guarantee of Article 14.

- Assessing Individual Dignity (Article 13): Based on the entire line of reasoning – finding the non-combination clause to be a rational policy choice within legislative discretion aimed at coordinating income support benefits – the Court concluded it was self-evident that the clause did not harm the dignity of the child as an individual and was not arbitrary or unreasonable legislation violating Article 13.

Therefore, the Court rejected F's claims under Articles 14 and 13 as well.

Conclusion and Significance

The Supreme Court's decision in Horiki dismissed the appellant's challenge, affirming the constitutionality of the legislative provision that prevented her from receiving both the Disability Welfare Pension and the Child Rearing Allowance simultaneously.

The significance of the Horiki judgment lies primarily in its elaboration and reinforcement of the principles regarding legislative discretion in the realm of social security, building upon the foundation laid by the Asahi case:

- Confirmation of Broad Legislative Discretion: Horiki strongly confirmed that the Diet possesses broad discretion in designing the specifics of the social security system intended to fulfill the mandate of Article 25. This includes decisions about eligibility criteria, benefit levels, and, crucially, how different benefits interact, including whether concurrent payments should be permitted or restricted.

- High Threshold for Unconstitutionality: The decision solidified the high threshold for judicial intervention. Courts will only declare such legislative choices unconstitutional if they are "markedly lacking in rationality" and represent a clear "abuse or deviation" from legislative discretion. This signals significant judicial deference to the Diet in socio-economic policy matters.

- Functional Analysis of Benefits: The case demonstrated the Court's willingness to analyze the underlying function of different social security benefits (e.g., income support vs. expense reimbursement) when assessing the reasonableness of non-combination clauses. Prohibiting the stacking of benefits deemed to serve a similar core purpose (income support) was seen as a potentially rational policy choice for ensuring fairness and managing resources.

- Balancing Act Affirmed: Horiki underscored the idea that creating a social security system involves balancing various goals, needs, and resources. Legislative choices that coordinate benefits, even if they disadvantage some individuals compared to others, are likely to be upheld as constitutional policy decisions unless they lack any rational basis.

In essence, the Horiki litigation reaffirmed the "abstract rights" interpretation of Article 25 and emphasized that the primary responsibility for giving concrete form to social rights lies with the legislature, whose policy choices in this complex field will generally be respected by the courts unless they cross the line into patent unreasonableness or arbitrary discrimination. It remains a key precedent illustrating the balance between constitutional social guarantees and legislative power in Japan's social security framework.

- Asahi Litigation (1967): Supreme Court on Japan’s Constitutional Right to Welfare

- Gaps in the Safety Net: Japan’s Supreme Court on Student Disability Pensions (2007)

- Sustainable Pensions vs. Recipient Rights: Supreme Court Addresses Pension Cuts (2023)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Child Support & Allowance Overview

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/topics/child-support/