The Hidden Switch: Japanese Supreme Court on Seller's Duty to Explain Critical Condo Safety Features

Date of Judgment: September 16, 2005

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, 2004 (Ju) No. 1847 – Claim for Damages

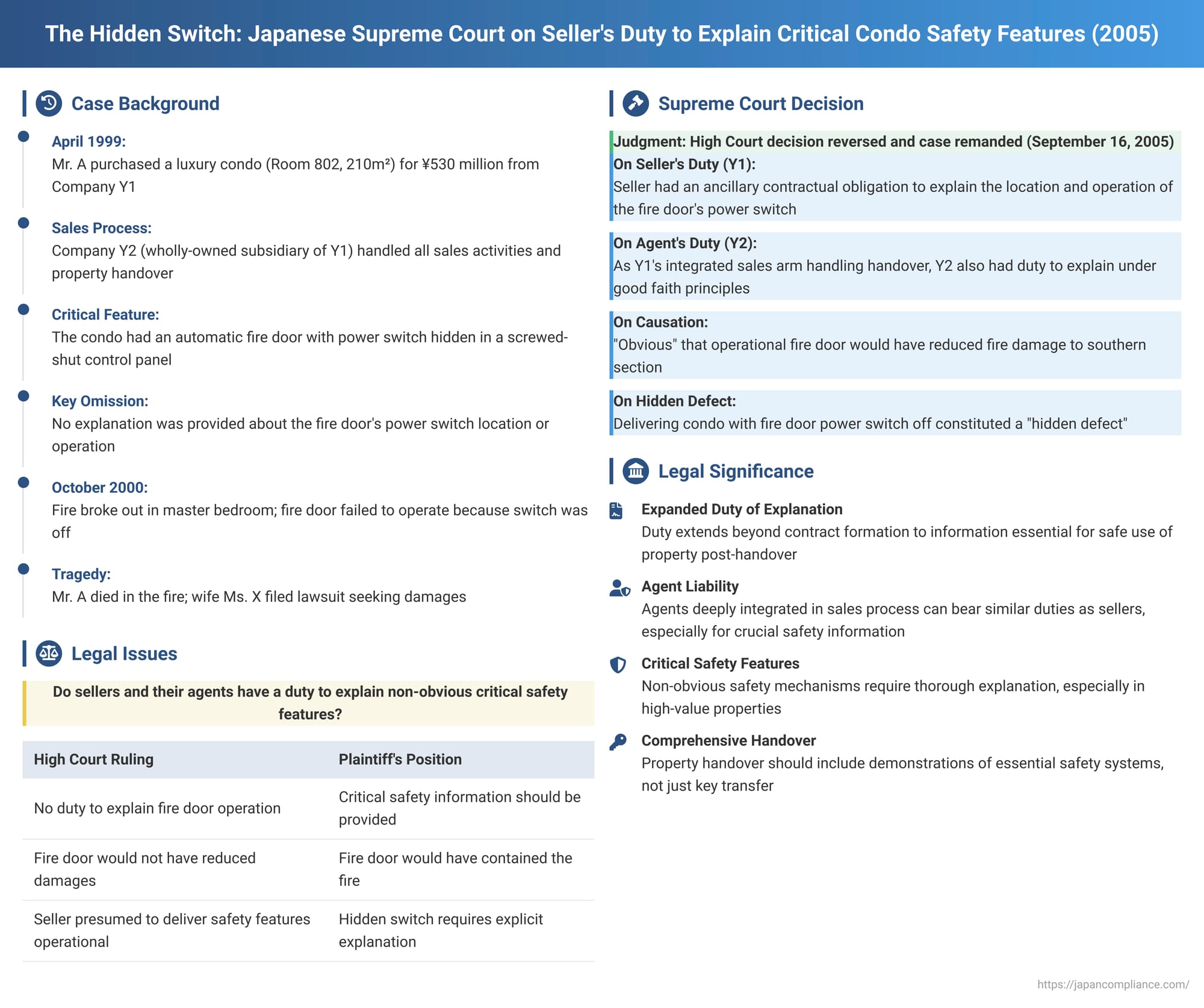

When purchasing a property, especially a high-value condominium, buyers rightly expect not only to receive the physical space but also crucial information pertinent to its safe and proper use. This is particularly true for safety features that may not be immediately obvious. A tragic case decided by the Supreme Court of Japan on September 16, 2005, underscores the serious obligations of sellers and their closely associated real estate agents to explain the operation of such critical, non-apparent safety mechanisms. The Court's decision delves into the nature of this duty to explain, differentiating it from information provided pre-contract, and clarifies the potential liabilities for failing to meet this obligation.

A Luxury Condominium, A Devastating Fire, and a Silent Fire Door

In April 1999, a purchaser, Mr. A, bought a spacious high-end condominium unit, identified as Room 802, with a floor area of approximately 210 square meters, for a price of 530 million yen from Company Y1, a real estate sales company. Company Y2, a real estate transaction firm and a wholly-owned subsidiary of Y1, played an integral role in this sale. Y2 was responsible for all sales-related activities for Y1's properties, including brokerage services, soliciting prospective buyers, providing explanations, and managing the handover of properties. This included the sale of Room 802 to Mr. A.

Room 802 was handed over to Mr. A in April 2000. Tragically, in October of the same year, shortly after Mr. A and his wife, Ms. X (the plaintiff in this case), moved in, a fire broke out in the master bedroom. The cause was determined to be Mr. A's mishandling of a cigarette.

The condominium unit was equipped with a significant safety feature: a fire door located near the center of the apartment. This door was designed to close automatically in the event of a fire, thereby separating the unit into northern and southern sections to prevent the spread of fire and smoke. However, during the October fire, this crucial fire door failed to operate. The reason was simple yet devastating: its power switch had been turned off. Consequently, the fire was not contained in the northern section (which included the master bedroom where the fire originated) and spread to the southern section, causing damage to almost all rooms there.

The power switch for this fire door was located inside a control panel within a storage closet in the unit. The design was such that its existence was not immediately apparent; the cover of the control panel was fixed with screws. Prior to Mr. A and Ms. X moving in, Company Y2 had provided them with an Important Matters Explanation document and various drawings. However, this explanation document made no mention of the fire door. While its location was indicated by a dotted line on one of the drawings, neither Company Y1 nor Company Y2 had provided any verbal or written explanation to Mr. A or Ms. X regarding the location of the fire door's power switch, its method of operation, or the mechanism of its automatic function during a fire.

Mr. A tragically died as a result of the fire. Ms. X, as his wife and legal heir, subsequently initiated a lawsuit seeking damages. In the High Court, Ms. X pursued claims against Company Y1 (the seller) based on seller's defect liability and breach of a contractual duty to explain. Against Company Y2 (the real estate agent), she claimed damages based on tort liability for its failure to provide necessary explanations.

The Lower Court's Dismissal: A Flawed Assessment

The Tokyo High Court dismissed all of Ms. X's claims.

Regarding the seller's defect liability claim against Y1, the High Court acknowledged that delivering Room 802 with the fire door's power switch in the "off" position constituted a "hidden defect" in the property. However, it denied that this defect led to increased damages. The High Court reasoned that even if the fire door had operated correctly, the extent of the damage to the southern section would not have been significantly less.

Concerning the duty to explain, the High Court found that Company Y2 did not have an obligation to explain the fire door's power switch location or operation to the buyer. The court reasoned that it was a natural presupposition that the seller, Y1, would deliver the unit with such an essential safety feature in a ready, operational state (i.e., with the power switch on).

Ms. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: Emphasizing the Duty to Inform

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated September 16, 2005, overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court found significant errors in the High Court's reasoning concerning both the duty to explain and the assessment of damages.

1. Seller Y1's Duty to Explain:

The Supreme Court determined that, based on the facts, the fire door was clearly a critically important piece of fire safety equipment. Given this, and the fact that its power switch was installed in a non-obvious location, the Court held that the seller, Company Y1, had an ancillary duty under the sales contract to explain the location of the power switch and its method of operation to Mr. A.

2. Real Estate Agent Y2's Duty to Explain:

The Court then addressed the liability of Company Y2. It noted that Y2 was not merely a passive broker but was a company established with Y1's full capital to handle Y1's real estate sales, including acting for or with Y1 in all related事務 (affairs/duties) from solicitation and explanation to the actual handover of properties. Y2 undertook all sales-related procedures for Room 802, including the handover to Mr. A, on behalf of Y1. Mr. A, in turn, relied on Y2's expertise and engagement in these matters when purchasing the unit.

Under these specific circumstances—where Y2 acted as an integral part of the sales operation in close cooperation with Y1 and was trusted by the buyer to manage these processes—the Supreme Court found that Y2 also bore a duty of explanation similar to Y1's, arising under the principle of good faith and fair dealing (shingi-soku). If Mr. A suffered damages due to Y2's breach of this duty, Y2 would be liable to him in tort. The Supreme Court criticized the High Court for dismissing Y2's duty without adequately examining the scope of Y2’s commission from Y1 and its concrete role in the sale and handover process, deeming this a failure of thorough deliberation leading to a misapplication of law.

3. Causation and Extent of Damages:

The Supreme Court strongly disagreed with the High Court's assessment that a functioning fire door would not have lessened the damages. The very purpose of the fire door was to automatically close during a fire and prevent its spread from one section of the unit to another. Therefore, the Court stated it was "obvious" that had the fire door operated, the extent and severity of fire and smoke damage to the southern section would have been less than what actually occurred when the door failed to close. The High Court's speculation that smoke and hot gases would have entered the southern section anyway during firefighting activities, or that extensive replacement of plasterboard, air conditioning units, and furniture might still have been necessary, was insufficient to conclude that the damages weren't exacerbated by the fire door's failure. The Supreme Court found this aspect of the High Court's reasoning to be contrary to empirical rules (experience-based logic) unless specific overriding circumstances were proven.

4. Hidden Defect (Seller's Defect Liability):

The Supreme Court did uphold the High Court’s initial finding that delivering Room 802 with the fire door's power switch turned off, rendering it non-operational, constituted a "hidden defect" in the object of the sale. Consequently, Company Y1, as the seller, was liable under the principles of seller's defect warranty (a concept that existed in the Japanese Civil Code prior to its 2020 reforms concerning contract non-conformity) for damages that had a reasonable causal nexus with the fire door's failure to operate. The core issue on remand would thus be the proper assessment of these damages.

The Nature of This "Duty to Explain": Beyond Contract Formation

The commentary accompanying this case highlights a crucial distinction about the type of "duty to explain" involved here. This was not primarily about providing information that would influence Mr. A's decision on whether or not to enter into the purchase contract. The contract had already been concluded.

Instead, the duty identified by the Supreme Court pertained to providing information essential for the safe and proper use and enjoyment of the purchased property after the sale—specifically, information about a critical safety feature whose operating mechanism was not obvious. This differs from, for example, a duty to explain the financial risks of an investment before the investment contract is signed (as in a case referenced by the commentary involving a credit union's duty to explain its risk of insolvency to a member before an investment contract was concluded). Information about the fire door switch was crucial for ensuring the safety of the occupants and the preservation of the property.

The timing for fulfilling such a duty could extend up to the point of handover of the property, and the explanation could be made to either the buyer (Mr. A) or his spouse (Ms. X), who would be residing there. The objective was to enable the occupants to ensure the fire door was operational.

Grounding the Duty of Explanation

The Supreme Court based Y1's duty on it being an "ancillary contractual obligation" (fuzui gimu). The commentary suggests this duty is not explicitly spelled out in the contract but derived from its purpose and context. Key factors the Supreme Court considered were the fire door's extreme importance as a safety device and the obscure, not-readily-apparent location of its power switch, which was effectively hidden inside a screwed-shut control panel.

The commentary further elaborates that for a high-value (530 million yen), large (approx. 210 m²), residential condominium unit on an upper floor, sold by a professional real estate development company (Y1), there's a heightened expectation of safety. It could be argued that there's an implied obligation on the seller to ensure such crucial safety features are not just physically present but are also made understandable and operable by the buyer. This is particularly so when the seller itself, or entities under its control, designed or implemented the system in a way that made the critical switch non-obvious. If the switch had been clearly visible and its function self-evident, the seller's duty to provide a specific explanation about its location might have been diminished or non-existent. The seller's actions in creating the non-obvious setup contributed to the need for an explanation.

Implications for Sellers and Real Estate Agents

This Supreme Court decision carries significant implications:

- Expanded Scope of Explanation: Sellers and developers have a responsibility to explain not just terms of a contract, but also critical operational details of the property, especially non-obvious safety features that are vital for the buyer's life, health, and property protection.

- Agent Liability: Real estate agents who are deeply integrated into the sales process, acting in close concert with the seller and undertaking responsibilities like handover, can also be held liable (typically in tort, based on good faith principles) if they fail to provide such crucial explanations. The mere fact that their role is "brokerage" might not shield them if their actual involvement is more extensive and they are relied upon by the buyer.

- Comprehensive Handover: The handover process for a property should be more than just a key transfer. It should include thorough explanations and demonstrations of essential systems and safety features, especially those that are not intuitive.

- Documentation: While not a substitute for clear verbal explanation of non-obvious critical features, sellers should ensure that instruction manuals and documentation for all equipment and safety systems are provided and that buyers are made aware of them.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Safety Through Information

The Supreme Court's 2005 judgment in the fire door case is a stark reminder of the profound responsibilities that sellers and their agents have towards buyers. It establishes that the duty to provide information does not necessarily end with the signing of a contract. For features critical to safety and the proper use of a property, especially those whose operation is not self-evident, there is a clear obligation to ensure the buyer is adequately informed. This decision champions the protection of the buyer, emphasizing that essential safety information is not a mere triviality but a fundamental component of what a buyer is entitled to receive, ensuring they can inhabit their new property with an appropriate understanding of its protective mechanisms. The ruling reinforces the idea that in property transactions, particularly concerning residential homes, the principles of good faith and the seller's ancillary contractual duties extend to safeguarding the well-being of the occupants through adequate information.