The Guardian of Overtime: Japan's Supreme Court on Democratically Electing Employee Representatives for "36 Agreements" (June 22, 2001)

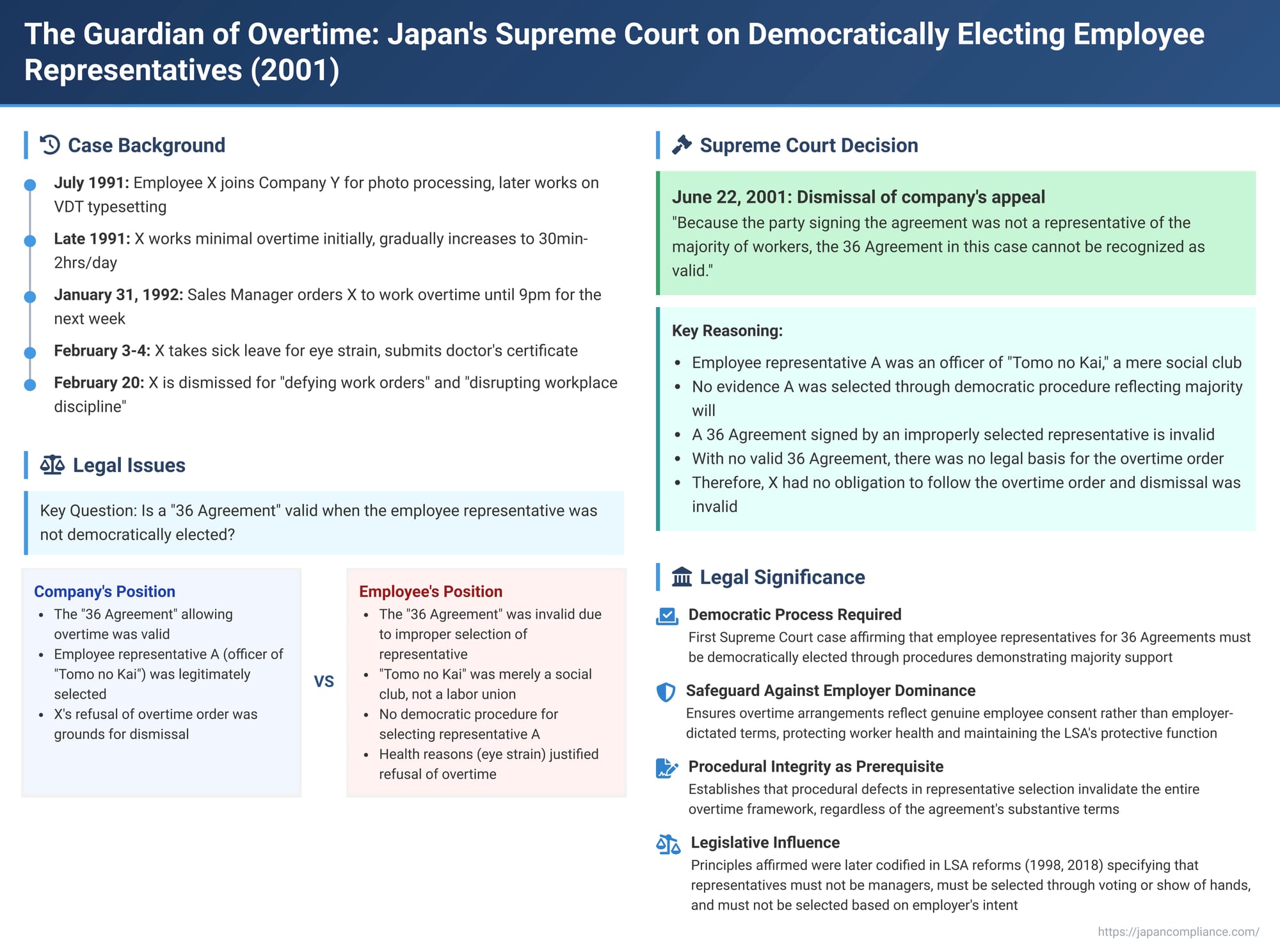

On June 22, 2001, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a concise but highly significant ruling in what is often referred to by commentators as the "Tookoro Case." This judgment underscored a fundamental prerequisite for the validity of "Article 36 Agreements" (労使協定 - rōshi kyōtei), which permit employers to assign overtime work: the employee representative signing such an agreement must be chosen through a democratic process that genuinely reflects the will of the majority of employees. The case highlights that procedural legitimacy in forming these agreements is paramount for them to have legal effect.

The Factual Tapestry: Overtime Demands, Health Concerns, and a Contested Representative

The dispute centered around Company Y, a business involved in manufacturing graduation albums, and its employee, X.

- Employee X's Role and Initial Work: X joined Company Y in July 1991, initially working in photo processing. By late August 1991, X transitioned to operating a computerized typesetting machine, a VDT-intensive task involving the creation of address lists.

- Company Y's Standard Hours and the "36 Agreement": Company Y's work rules stipulated an eight-hour workday, from 8:30 AM to 5:30 PM, with a 60-minute break. To manage periods of high demand, the company had an "Agreement on Overtime and Holiday Work," commonly known as a "36 Agreement" under Article 36 of the Labor Standards Act.

- This 36 Agreement cited the primary reason for overtime as being "when a large volume of orders is received at once and delivery by the deadline is necessary".

- The agreement covered various types of work, including "sales, administration, public relations, plate making, and block copy preparation".

- It specified permissible overtime hours which varied based on gender and the time of year. For instance, for male employees, it allowed up to 3 hours per day from April to October and 6 hours per day from November to March. For female employees, the limits were 1 hour per day from April to October and 2 hours per day from November to March, with a weekly cap of 6 hours irrespective of the season. Monthly limits were set at 50 hours for men and 24 hours for women, and annual limits at 450 hours for men and 150 hours for women.

- Critically, this 36 Agreement was signed and sealed on behalf of the employees by A, an officer of the "Tomo no Kai" (Friendship Club). The Tomo no Kai was an internal organization composed of all officers and employees of Company Y.

- Escalating Overtime and Health Issues: Initially, X worked minimal overtime. However, around late September 1991, an informal arrangement was made within X's department for employees to work overtime until 7:00 PM. Consequently, from early October, X began working approximately 30 minutes to 1 hour and 45 minutes of overtime daily. In November, Company Y's Sales Manager, B, attempted to persuade X to take on more overtime hours. X declined, citing eye strain from the VDT work and stating that extended overtime was not feasible for health reasons.

- The Overtime Order and Refusal: From January 1992, X typically worked 30 minutes to 2 hours and 15 minutes of overtime, usually finishing between 7:00 PM and 7:30 PM. Around January 20th and 30th, Supervisor C requested X to further increase overtime hours, but X did not consent. On January 31st, Sales Manager B issued a direct overtime order to X: "For the next week, starting Monday, work overtime until 9:00 PM".

- Medical Leave and Return to Standard Hours: On February 3, 1992, X took a day of sick leave and visited a medical institution due to eye strain. The following day, February 4th, X submitted a doctor's certificate to Company Y. From that day forward, X ceased working overtime and consistently finished work at the scheduled end time.

- Dismissal: On February 20, 1992, Company Y's President, D, informed X that he was being dismissed. The company characterized this as an ordinary dismissal, not a disciplinary one, but cited various clauses from its work rules as grounds. These included provisions related to "unjustly defying work-related instructions/orders and disrupting workplace discipline" (Article 42, Section 3), "receiving repeated disciplinary actions under Article 41 with no prospect of improvement" (Article 42, Section 9), "violating company rules or instructions without reason and disrupting internal order" (Article 41, Section 3), and "other acts deemed equivalent by the company" (Article 42, Section 10).

- X's Legal Action: X filed a lawsuit against Company Y, asserting that the dismissal was invalid. X sought confirmation of his employment status, payment of unpaid wages, and compensatory damages for emotional distress, alleging the dismissal constituted either a tort or a breach of contract.

The Lower Courts' Rulings: Focus on the Flawed 36 Agreement

- The First Instance Court (Tokyo District Court): This court found X's dismissal to be invalid. A key reason for this decision was the invalidity of the 36 Agreement itself. The court determined that A, the individual who signed the agreement as the employee representative, was an officer of the "Tomo no Kai," which it characterized as a "social club" (親睦団体 - shinboku dantai) rather than a legitimate representative body. The court found that A had "automatically" become the employee representative, indicating a lack of proper selection procedure. The court also considered that X had already performed a substantial amount of overtime and had refused further overtime orders due to legitimate health concerns (eye strain). While X's claims for reinstatement and unpaid wages were upheld, the claim for emotional distress damages was dismissed. Company Y appealed this decision.

- The Second Instance Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court upheld the District Court's decision, dismissing Company Y's appeal.

- The High Court referenced a previous landmark Supreme Court decision (the Hitachi Manufacturing Musashi Plant Case, judgment of November 28, 1991) to outline the conditions under which an employee incurs an obligation to work overtime: a valid 36 Agreement must be concluded with a majority union or representative and filed with the authorities, and the company's work rules must reasonably provide for overtime within the scope of that agreement.

- Crucially, the High Court delved into the requirements for the valid selection of an employee representative (where no majority union exists) to sign a 36 Agreement. It cited a Ministry of Labour administrative circular (Ki-hatsu No. 1, dated January 1, 1988) which stipulated that for a selection to be deemed lawful, two conditions must be met: firstly, employees at the workplace must be given an opportunity to judge the suitability of the candidate to conclude a 36 Agreement on their behalf; and secondly, a democratic procedure must be followed which demonstrates that a majority of the employees at the workplace support the chosen candidate.

- Applying these principles, the High Court found that the "Tomo no Kai" was merely a social club and not a labor union. It further stated that there was "no sufficient evidence to acknowledge that A was democratically selected" as the majority representative of the employees.

- Based on this finding, the High Court concluded that the 36 Agreement was invalid. Consequently, the overtime order issued to X, which relied on this agreement, was also invalid, meaning X had no obligation to comply.

- The High Court also offered an alternative ground for its decision: even if the 36 Agreement had been valid, X had unavoidable reasons—namely, the diagnosed eye strain—that justified his inability to comply with the specific overtime order.

Company Y further appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: A Defective Agreement Means No Obligation

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed Company Y's appeal in a succinct judgment.

The Court stated that the Tokyo High Court's findings of fact were well-supported by the evidence presented in the lower court proceedings.

Under these established facts, the Supreme Court directly addressed the core issue: "because the party signing the agreement [A] was not a representative of the majority of workers, the 36 Agreement in this case cannot be recognized as valid".

As a direct consequence of the 36 Agreement's invalidity, the Court concluded that "Employee X did not have an obligation to follow the overtime order".

Therefore, the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's ultimate judgment that X's dismissal was invalid as being correct and justifiable. The Supreme Court found no merit in the appellant's arguments, stating they either merely criticized the High Court's discretionary assessment of evidence and fact-finding or were based on unique interpretations or misunderstandings of the High Court's ruling, and thus could not be adopted.

Unpacking the Significance: Democratic Representation in Labor Law

The Supreme Court's decision in the Tookoro Case, while brief, carries profound implications for Japanese labor law, particularly concerning the procedural requirements for establishing legitimate overtime frameworks. The commentary accompanying this case sheds further light:

The Indispensable Role of the Article 36 Agreement

The Labor Standards Act (LSA) sets default limits on working hours (e.g., 40 hours per week, 8 hours per day). Article 36 of the LSA provides a critical mechanism for employers to legally require employees to work beyond these statutory limits (overtime) or on statutory holidays. This is achieved by concluding a written labor-management agreement (the "36 Agreement") with the appropriate employee representative and filing it with the Labor Standards Inspection Office. Such an agreement effectively legalizes work that would otherwise be a violation of the LSA. However, it is important to note, as affirmed in previous jurisprudence like the Hitachi Manufacturing case, that the 36 Agreement itself does not automatically impose an individual obligation on employees to work overtime; this obligation typically arises from provisions in the work rules or employment contract that are themselves conditional upon a valid 36 Agreement being in place.

Who is the "Majority Representative"?

LSA Article 36 specifies that the agreement must be concluded with either:

- "The labor union organized by a majority of workers at the workplace", or

- If no such majority union exists, "a person representing a majority of the workers" at that workplace.

This concept of a "majority representative" is a recurring feature in Japanese labor law, appearing in various LSA provisions, such as those concerning the employer's management of employee savings (Article 18, Paragraph 2), agreements for wage deductions (Article 24, Paragraph 1, proviso), and the requirement to hear opinions when creating or changing work rules (Article 90, Paragraph 1).

The central issue in many workplaces, and in the Tookoro case, is how this "person representing a majority of the workers" is to be chosen when there isn't a union that already represents the majority.

The Non-Negotiable Requirement of Democratic Selection

The Tookoro case powerfully affirms that the selection process for this majority representative must be democratic and genuinely reflect the collective will of the employees.

- The High Court's reasoning, endorsed by the Supreme Court, explicitly relied on the principle that employees must have a fair opportunity to assess the suitability of a candidate for representing them in 36 Agreement negotiations, and that the selection must be supported by a majority through a democratic process.

- If a 36 Agreement is concluded at the employer's sole discretion, or with a representative not truly chosen by the employees, the protective intent of LSA Article 32's working hour regulations would be nullified, potentially jeopardizing workers' health and well-being. The 36 Agreement system is designed to prevent such outcomes by ensuring worker input.

- The commentary notes that a secret ballot is the most appropriate method for selecting a representative to ensure freedom from employer influence.

The Supreme Court's affirmation that A, an officer of the "Tomo no Kai" (a social club, not a union), who was not proven to have been democratically elected, could not validly conclude the 36 Agreement is a straightforward but vital confirmation of this principle. The decision that an agreement made with an improperly selected representative is invalid is seen as a natural and supportable conclusion. The high significance of this case lies in the Supreme Court's clear endorsement of the necessity for democratic election of the majority representative in the absence of a majority union.

Evolution of Legal Standards for Representative Selection

While the Tookoro case was decided based on the legal framework and administrative guidance existing at the time (like the 1988 circular mentioned by the High Court ), the principles it upheld have since been more explicitly codified.

- Subsequent amendments to the LSA Enforcement Regulations (following 1998 reforms) formally stipulated requirements for the majority representative:

- The person must not be a managerial or supervisory employee.

- The person must be selected through a procedure such as voting or a show of hands, conducted for the clear purpose of choosing someone to conclude LSA-stipulated agreements.

- Further clarification came with the 2018 LSA reforms, which added the requirement that the representative must "not have been selected based on the employer's intent".

- A 1999 administrative circular also clarified that procedures like "worker discussions" or "circulated resolutions" could qualify as democratic if they clearly establish that a majority of workers support the individual's appointment.

These later developments reinforce the core message of the Tookoro judgment: the process must be transparent, free from undue employer influence, and demonstrably reflect majority employee consent.

The Unaddressed Question: Overtime Refusal and Health

Interestingly, the Supreme Court in its Tookoro judgment did not address the High Court's alternative finding – that even if the 36 Agreement had been valid, Employee X had justifiable, health-related reasons (eye strain) for refusing the specific overtime order until 9 PM. The Supreme Court likely deemed it unnecessary to rule on this point because the foundational 36 Agreement was already found to be invalid, meaning X had no overtime obligation to begin with.

However, the commentary points out that this underlying issue remains an important area of labor law. Even when a valid 36 Agreement exists and the work rules concerning overtime are deemed reasonable, the question of when a specific overtime order might constitute an abuse of the employer's rights is critical. Factors such as an employee's documented health conditions (like X's eye strain), the proximity of the overtime order to the actual workdays it affects, and the sheer length and frequency of the overtime demanded could all be pertinent in determining whether a particular order is abusive or unreasonable.

Conclusion: Procedural Integrity as the Cornerstone of Lawful Overtime

The Tookoro Supreme Court decision serves as a crucial reminder that procedural integrity is fundamental to the legality of overtime work in Japan. The democratic selection of the employee representative who signs the Article 36 Agreement is not a mere formality; it is a substantive requirement that ensures the agreement reflects the genuine consent of the workforce. Without a validly chosen representative, the 36 Agreement is void, and any overtime obligations purportedly based upon it collapse. This case firmly places the onus on employers to ensure that the selection process for employee representatives is transparent, fair, and truly representative of the majority will, thereby upholding both the letter and the spirit of Japan's Labor Standards Act.